Family : Aetobatidae

Text © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

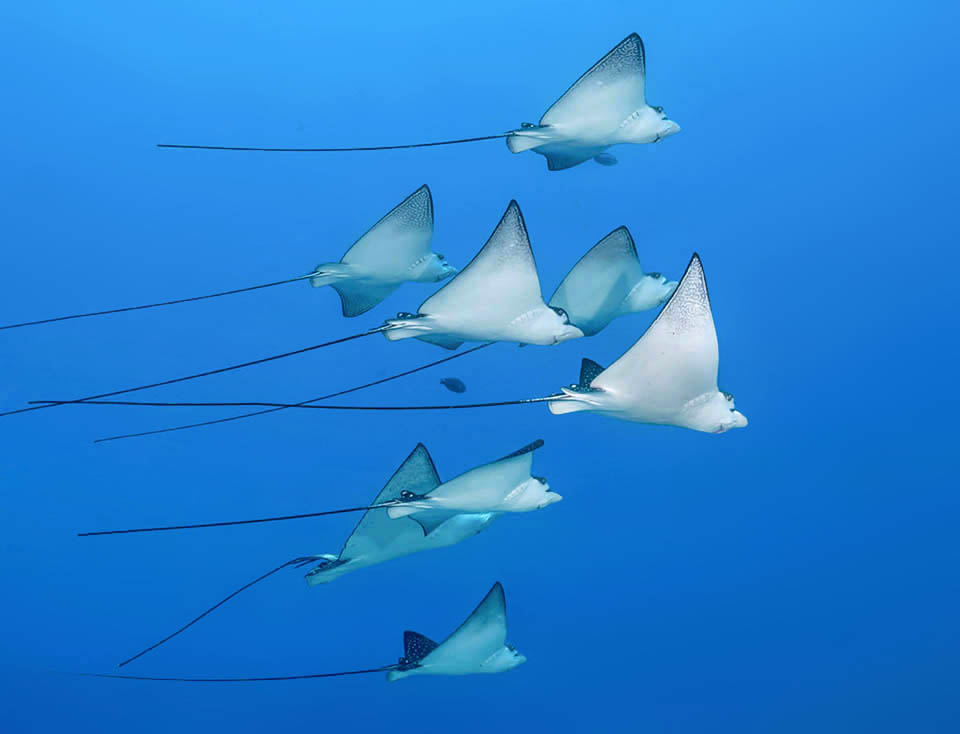

Ocellated eagle ray or White-spotted eagle ray (Aetobatus ocellatus) swims often in dense schools, even on long distances close to the surface of the sea © David Rolla

Aetobatus ocellatus ( Kuhl, 1823 ) known as White-spotted eagle ray or Ocellated eagle ray, belongs to the class Chondrichthyes, that of the cartilaginous fishes, without bones, grouping cognate rays, sharks, chimaeras and forms.

It belongs to the Myliobatiformes, fishes having no anal fin, with a very depressed body and eyes on the back, gill openings on the abdomen and mainly protruding jaws.

For the genus, that counts only 5 species, a small family has been created, all for them, rightly called the Aetobatidae.

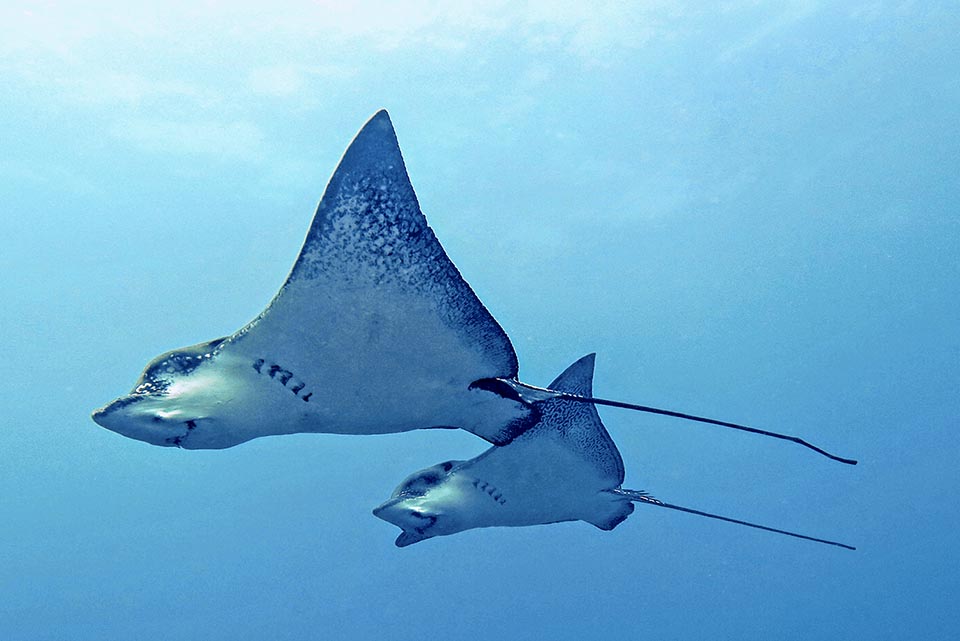

Here in profile with well visible the five gill fissures per side on the candid abdomen, whilst the back is dark greenish grey with spots and rare white ocelli. It is present in tropical Indo-Pacific, unlike Aetobatus narinari, similar species once confused but with different structure of the gene NADH2 and swimmming in the Atlantic © David Rolla

Aetobatus comes from the Latinized old Greek “ἀετός” (aetos) = eagle and βάτης (bâtis) = ray, due to its majestic swimming and the speed allowed by the large pectoral fins.

The generic term ocellatus reminds us, in Latin, the countless spots and white rings that stand out on the dark background of the elegant mimetic livery: a myriad of small eyes for hiding the fish on the bottoms, in clear contrast with the white ventral side that, seen from below, in turn disappears in the bright shimmer of the sea.

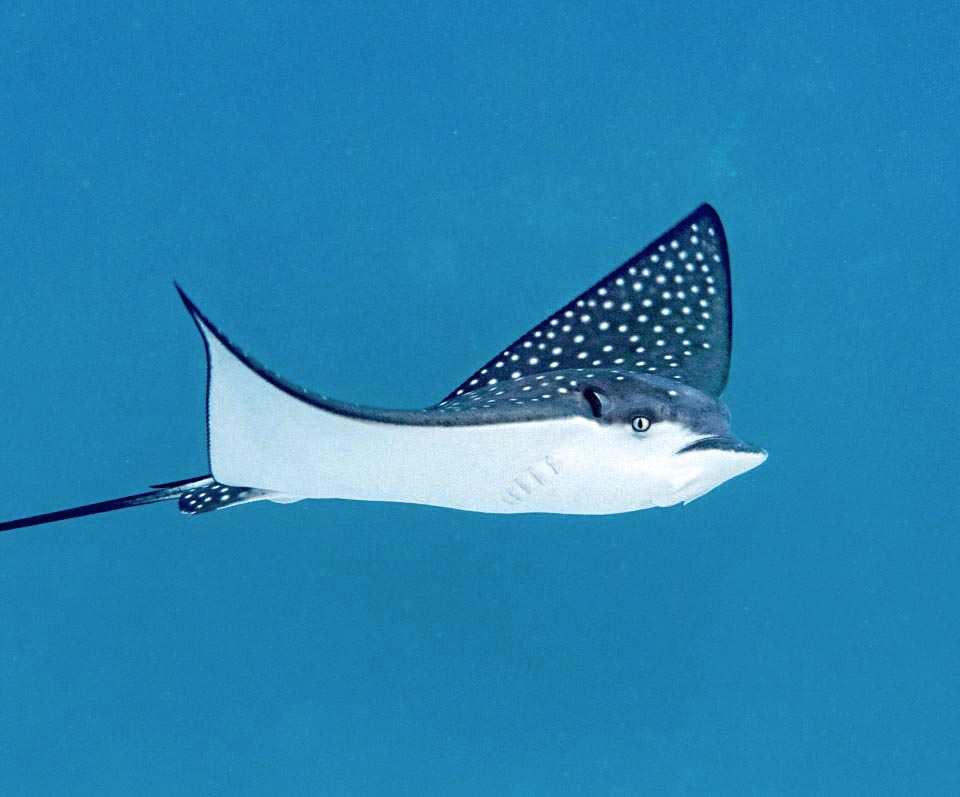

The snout, at first sight pointed, is duckbill-like and over the eyes we note a huge nostril © Michael Eisenbart

Zoogeography

Aetobatus ocellatus occupies a very vast range in the tropical Indo-Pacific. We find it from the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf along all eastern African coast up to South Africa.

Indicatively, after Madagascar and the adjacent islands of Mayotte, Comoros, Réunion and Mauritius, it is present at the Seychelles, Maldives, Sri Lanka, India, Myanmar, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, Australia and New Caledonia that marks the eastern limit of the species. Northwards, it is present in the waters of Philippines, Vietnam, Taiwan, Hong Kong, China and South Japan.

Even 3 m wide, can reach the length of 8 m, tail included, if this did not accidentally break as often occurs. Its maximum weight is of about 200 kg © Michael Eisenbart

Eastwards, after Micronesia, has colonized the Marshall Islands, Fiji, Tonga, Samoa, Hawaii, Tahiti and French Polynesia up to Easter Island.

Ecology-Habitat

Even if it lives at 20-25 m, it’s a benthopelagic fish that may be found also by the sea or at 100 m of depth in various environments, including the brackish waters of the river mouths. It loves the sandy bottoms and the submerged grasslands but does not ignore the madreporic formations that it often memorizes to the point of finding them again even after long voyages.

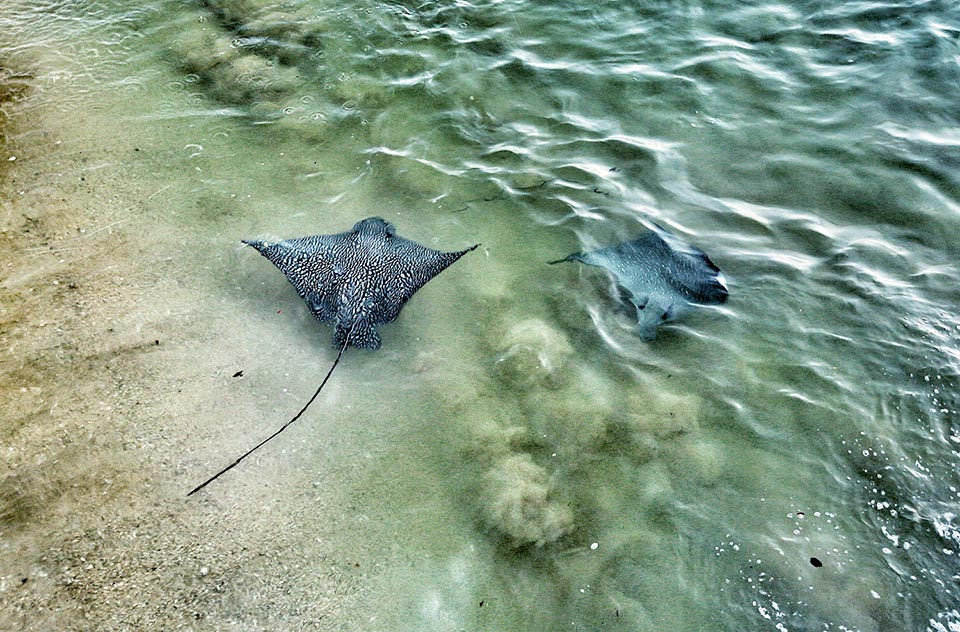

Even if it lives mostly between 20 and 25 m, it’s a benthopelagic fish that can be found also by the sea, like in this photo, or at 100 m of depth © Jon Kevin Okagawa

Morphophysiology

Of rhomboid look, it can reach the length of 3 m and is 8 m long, tail included, if this, if exceeding the double of the body, has not accidentally broken. as often occurs. The maximum weight reached is about 200 kg.

The back, dark greenish grey with spots and rare white ocelli, is quite similar to that of Aetobatus narinari with which was once mistaken, but the latter has a paler background colour, a different structure of the gene NADH2 and is found in the Atlantic only.

Aetobatus ocellatus eats benthic animals it finds helped by special sensory organs plowing through the muddy bottoms with its flat snout © Brian Cole

The snout, that seen in profile appears pointed, is flat, duckbilled, with only one row of teeth per jaw, interlocking arranged for better breaking shells and carapaces. Close to the eyes we note two big nostrils and, at the base of its enormous fins, 5 showy branchial fissures per side.

Like all Myliobatiformes it has no anal fin, but here are absent even the caudal and the pelvic, of modest size, are rounded. The tail, similar to a long whip, has at the base a small dorsal fin with 2-6 relatively long poisonous spines dangerous also for man.

Here after raising a cloud of dust. It eats mollusks, crustaceans, annelids, sea urchins and fishes. The tiny dorsal fin has 2-6 venomous spines dangerous also for man © Paul Asman and Jill Lenoble

With the ample movements of the pectoral fins it is a fish able to cross the oceans without any effort and can splash out of water in order to get rid of the parasites or to escape the predators.

Ethology-Reproductive Biology

Aetobatus ocellatus nourishes of benthic animals it finds helped by special sensory organs, and for finding the nest, often plows the muddy bottoms with its flat snout raising a cloud of dust. Octopuses, oysters, clams, gastropods, hermit crabs, crabs, lobsters and other crustaceans stand at the base of its diet, without forgetting the sea urchins, some little worms and fishes such as the mullets that are also looking for food on the bottom.

Here starts again dirty of sand. It is capable to memorize the madreporic formations and to find them again even after long voyages © Barry Fackler

The males reach the sexual maturity when about 4-6 years old when they are about 1 m long, and the females a little later around the 1,3 -1,5 m. The fecundation, lasting about one minute and a half, is internal. The male immobilizes the female holding her with the teeth and introduces the gametes thanks to two copulatory organs, called pterygopodia, born from the cylindrical extension of the posterior flap of the pelvic fins.

The females, ovoviviparous, have a long pregnancy of 2-3 years and may deliver up to 10 infants, even if usually they are 4 and at times only one. These at the beginning nourish of the yolk and then grow up absorbing fat and proteins from the uterine fluids. Obviously, the size at the birth is very variable and varies from 18 to 50 cm.

Males reach sexual maturity by the 4-6 years when they measure about 1m of width, and the females little later when 1,3-1,5 m © Mark Rosenstein

A female may mate with more males without scruples, at times even four in one hour, during the festive gatherings that occur on the sandy bottoms during the reproductive season, and when the males are lacking, exist also rare cases of parthenogenesis: of infants that come to life from eggs not fecundated.

Aetobatus ocellatus is mainly preyed by the Great hammerhead (Sphyrna mokarran) and by the Silvertip shark (Carcharhinus albimarginatus) to which we must add the man with the trawler fishing that does not leave often the females the time to grow up and reproduce.

Fecundation is internal. The females, ovoviviparous, mate even with more males and exist rare instances of parthenogenesis, with infants born from not fecundated eggs © Karen Honeycutt

The flesh of Aetobatus ocellatus is edible, the dried tail is sold as a souvenir for tourists. The young end up sometimes in the large public aquaria, because it is a species easy to feed well adapting to the oceanic pools where it goes swimming tirelessly, amazing the public, in elegant formations.

The resilience of the Ocellated eagle ray is very low, as 4,5 to 14 years are needed for doubling the members decimated by the events, and the fishing vulnerability index is dramatically high, marking already 86 on a scale of 100. As a consequence, Aetobatus ocellatus appears nowadays as ”VU Vulnerabile” in the Red List of the endangered species.

Subadult looking for food. Unluckily, the Ocellated eagle ray appears now as “vulnerable” in the Red List of the endangered species © François Libert

Synonyms

Myliobatus ocellatus Kuhl, 1823; Aetomylaeus ocellatus (Kuhl, 1823); Myliobatis ocellatus Kuhl, 1823; Raja tajara Forsskål, 1775; Raja tajara hörraeka Forsskål, 1775; Raja mula Forsskål, 1775; Raja guttata Shaw, 1804; Aetobatus guttatus (Shaw, 1804); Raja quinqueaculeata Quoy & Gaimard, 1824; Myliobatis eeltenkee Rüppell, 1837; Myliobatis macroptera McClelland, 1841; Raja edentula Forster, 1844; Goniobatis meleagris Agassiz, 1858; Myliobatis punctatus Miklukho-Maclay & Macleay, 1886; Aetobatus punctatus (Miklukho-Maclay & Macleay, 1886); Pteromylaeus punctatus (Miklukho-Maclay & Macleay, 1886).

→ For general information about FISH please click here.

→ For general information about CARTILAGINOUS FISH please click here.

→ For general information about BONY FISH please click here

→ To appreciate the BIODIVERSITY of CARTILAGINOUS FISH please click here.

→ To appreciate the BIODIVERSITY of BONY FISH please click here.