The anchovies factory. On the Atlantic coast of South Africa there is a factory that each year treats thousands of tons of anchovies fished in the area. In few minutes they are transformed into oil and flour.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

Nothing is wasted.

From a ton of anchovies you can get 220 Kilos of fish flour and from 30 to 85 litres of raw oil.

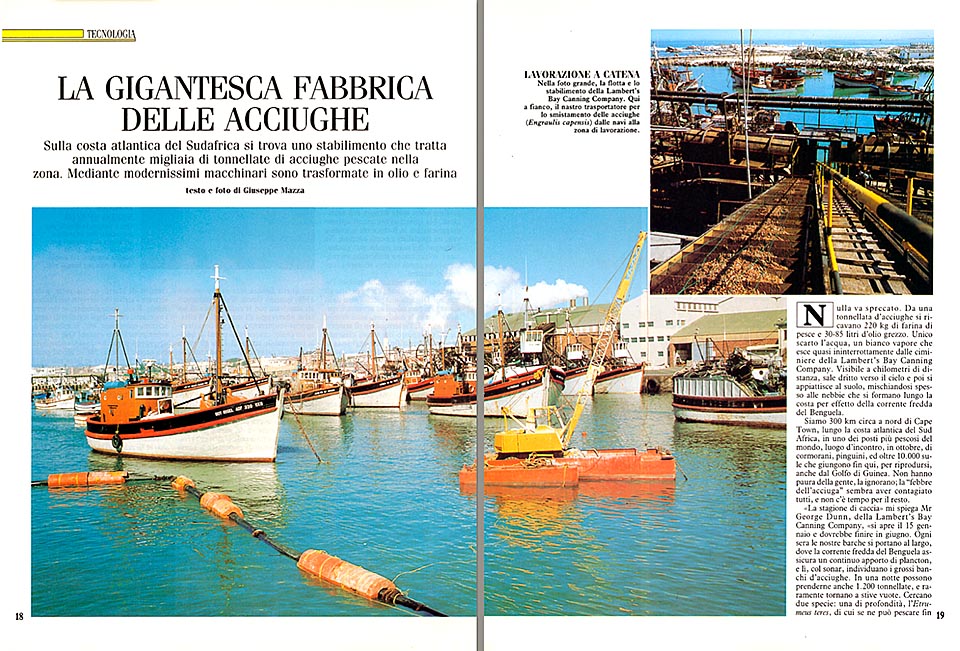

The only waste is water, a white steam which gets out almost uninterruptedly from the chimneys of Lambert’s Bay Cunning Company.

Visible from Kilometres far away, it goes up straight to the sky. It dazzles like snow, and then flattens to the ground, mixing often with the fogs that develop along the coast, caused by the cold stream of Benguela.

An unreal atmosphere, much alike a Scandinavian port, where strange, black phantoms wearing blue overalls are moving among squeaks of birds.

We are about 300 km north of Cape town, along the Atlantic coast of South Africa, in one of the most crowded of fishes areas in the world, meeting point, in October, of cormorants, penguins and more than 10.000 gannets which come here, for breeding, even from the Gulf of Guinea.

They are not scared of men: they just ignore them, and, apart few tourists and scholars, the man does the same. The “fever of the anchovies” seems to have infected everybody, and there is no time for other things.

“The hunting season”, tells me Mr. George Dunn, Public Relations officer of the Lambert’s Bay Cunning Company, “opens on January 15th, and should close in June.

Every evening, our boats go to the open sea, where the Benguela cold stream provides a continuous amount of plankton, and there, with the sonar, they detect the bid herds of anchovies.

In one night, they can catch even 1200 tons, and seldom they come back with the holds empty. They look for two species: one, which lives in the depths, the Etrumeus teres, of which they can catch as much as they want, and one of surface, the Engraulis capensis.

This one is easier to catch, but being the main food for the sea birds, every year the fishing ministry fixes a maximum quota, which is not to be trespassed.

Usually 34.000 tons, to which you can add, if the season is good, 20.000 tons more.

Fishing goes on then till the whole month of October, and we are given just 2-3 months for the maintenance of the boats and the plants”.

“But, the birds don’t get any harm?”, I interrupt, looking at the gannets and the cormorants which, full of fish for their nests, are continuously passing in front of the windows of the factory.

“Much has been discussed in the past”, George Dunn goes on, “about the possible damages that our activity might cause to the biological balance and particularly to the sea birds.

But at Lambert’s Bay, gannets are increasing, and a clever test has shown last year, without any doubt, how much the fish is still copious.

Gannets, as it’s well known, are among the biggest sea birds: they lay only one egg, and the youngest, authentic devourers of anchovies, do grow up at the incredible rhythm of 1 kg per month.

We have thought then, at the time of the disclosure of the eggs, to add to a nest a freshly born chick, taken away from another couple.

Should the fish become scarce, in spite of the good will of the adoptive parents, one of the two chicks should certainly die due to the voracity of the other one.

And, on the contrary, by the end of the season, both were well over the standard weight.

Therefore, for the moment, the availability of the anchovies is over the needs of the birds”.

They tell us the fleet is back.

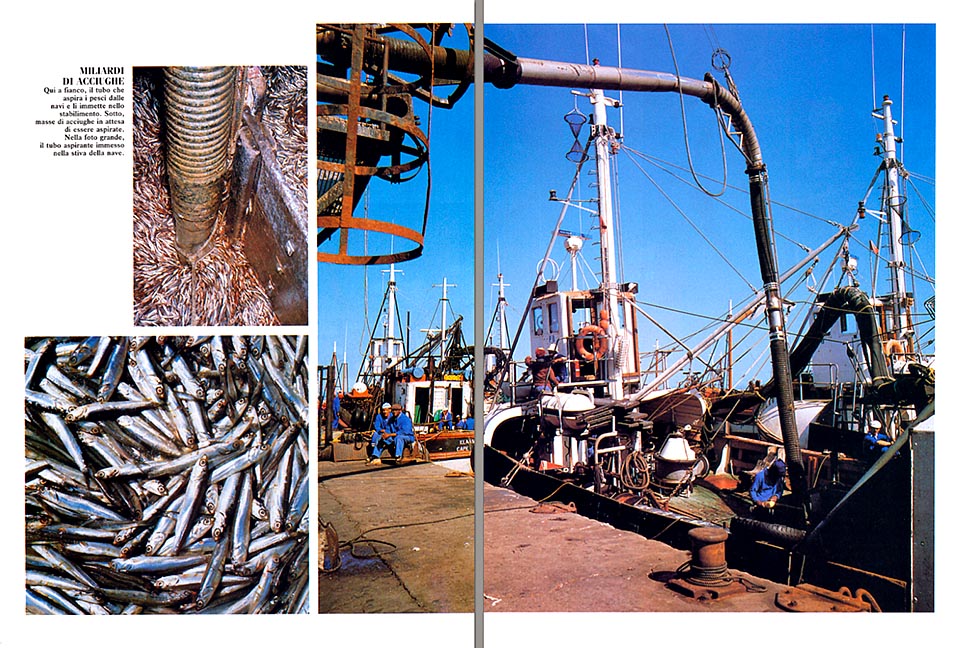

Eight white fishing boats, with an elegant red and black board, are queuing for getting alongside, while a huge suction pipe noisily aspirates mountains of sparkling anchovies from the holds.

They will loose their brightness at once, as well as most of the scales, in a rotating cylinder, which continuously conveys them, bruised, to a transporting device.

They reach the factory, and their way into huge cement tanks.

“There are 8 basins of 100 tons each”, states George Dunn, “but they will not remain there for a long time.

The work begins at once, and when the last boats are alongside, the cargo of the first ones has been already treated”.

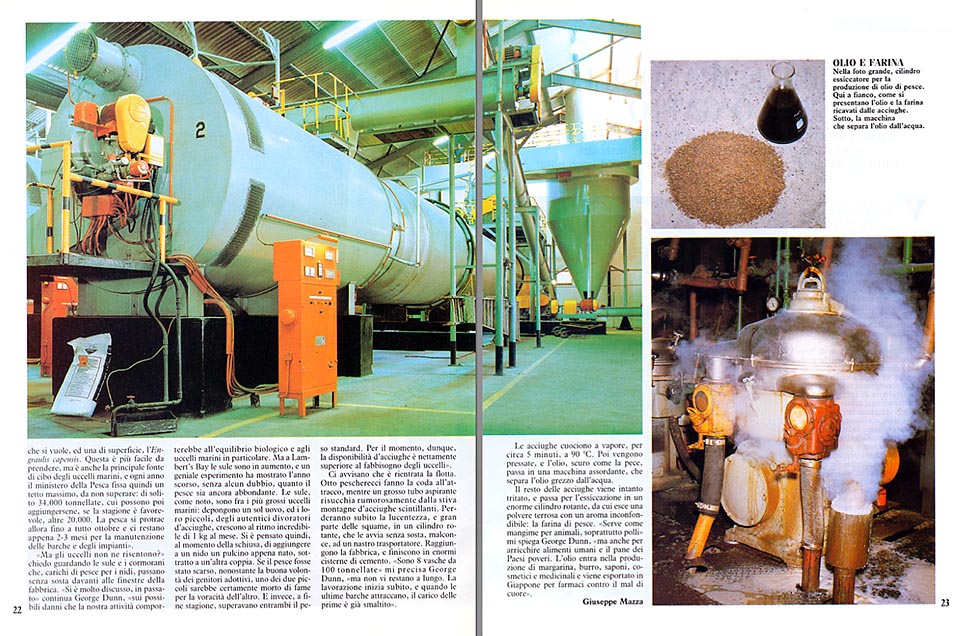

The anchovies cook by steam, for about 5 minutes, at a temperature of 90 °C. Then, they are pressed, and the oil, as dark as pitch, goes into a strange deafening machine, worthy of Capt. Nemo’s submarine or a Fellini’s movie.

It shakes, between clouds of steam, on a steel platform, parts and separates, endlessly, the raw oil from the water.

The flesh and the bones of the anchovies are, in the meantime, crumbled and go, for drying up, in an enormous rotating cylinder, from which gets out an earthy dust with an unmistakable aroma: the floor fish.

“It is used as food for animals, mainly poultry”, George Dunn explains, “but also to enrich human food and the bread for poor countries.

The oil is a component of margarine, butter, soaps, cosmetics and medicines.

It has a high contents of EPA, and is exported to Japan, for medicines against heart diseases”.

Also, the “anchovies chicken” popular in all South African restaurants, seem to assimilate this precious molecule, and as per recent studies, done in USA, they might prove to be the best preventive treatment against heart stroke.

SCIENZA & VITA NUOVA – 1989