In Australia there is a greenhouse just for them. The Jungle of Butterflies in Antibes. The breeding of butterflies in large greenhouses open to the public.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

Even if they have an unquestionable systematic value, butterflies pinned in the museums, are by now a memory of the past.

Small corpses pierced through, with yellowish tags written with India ink, and passing-by students, who, forgotten immediately the scientific names, assimilated at once the idea of hunting. Groups of lively Teresas and amateurish entomologists, looking for the few surviving butterflies of the industrial civilization, to give, often a push with the shoulder, or, even, the finishing blow to the rarest forms.

In the last century, the population of the Italian lepidoptera has decreased of the 99%; in other wordings, where before there were 100 butterflies flying, nowadays, there is only one. Apart collectors, they have fallen down under the blows of pollution and of insecticides, but mainly under those of the strong modifications of the environment.

The “wet areas”, which once were giving hospitality to several species, are now, almost all, “reclaimed”, and chemical fertilizers, scatter profusely in the fields, spread with the water in the territory, joining the nitrogen oxides emitted by the exhausts of the cars, which already contaminate in all sides meadows and woods.

The lands get manured, and many plants, born for diets poor in nitrogen, resent on this, whilst others take advantage and smother the first ones, with an exaggerated growth. So, if by the beginning of the century, a meadow was giving hospitality to 50 types of plants, now it has no more of ten of them. For the cows, and the Sunday tourists, it does not change too much, but for the caterpillars of butterflies, which, through a selective feeding, nourished only of the other 40 species, die from hunger, even before being poisoned by the insecticides.

The “red book” of the Italian lepidoptera counts more than 50 butterflies at risk, between them the well known Apollo, which, even if in some favourable years, can seem frequent in our mountains, is in clear falling off. In 1973, it has the gloomy privilege of being the only invertebrate included by the International Convention of Washington, in the listing of animals threatened of extinction, for which the trade and the possession must be controlled.

And the boys who were visiting the museums? They have grown up, but thanks to the ecological education received, they often continue their vocation of hunters-collectors. And nowadays, when in Italy there is not too much, they look the big exotic butterflies, not always coming from breeding, killed for compositions, and small frameworks of horrible taste; a consumption of tens of millions of specimen per year, with an invoicing of 35 millions of Dollars and 20.000 workers in the third world.

A few years ago, a major Italian women magazine has reached the point of compliment the readers with small frameworks coming from Taiwan, where, for convenience, the wings of exotic butterflies were glued on a thin card close to the drawing of the body. A nice “promotion”, supported by nice looking models. Who cars, if, later on, some species disappear.

Luckily, in 1981, when the city zoos were classified as lagers, and a big quantity of TV documentaries did humiliate their ancient pedagogical value, in England, somebody had the idea to make money with living butterflies, creating in Syon Park, close to London, the first Butterfly house in the world. A luxuriant tropical forest, between magic crystal walls; a greenhouse with hundreds of exotic butterflies at liberty, which don’t fear the man, and alight on the dresses, often mistaking the perspiration of the tourists as nectar, and a business which reaches almost the 250.000 visitors per year.

The premises for the success were simple: no criticisms from the protectionists of animals, seen that for the butterflies, a greenhouse without predators, and rich of food, is an earthly heaven, by sure not narrow, low feeding costs; and, furthermore, a new way of presenting the lepidoptera, bound more to ecology and life, rather than to the systematics.

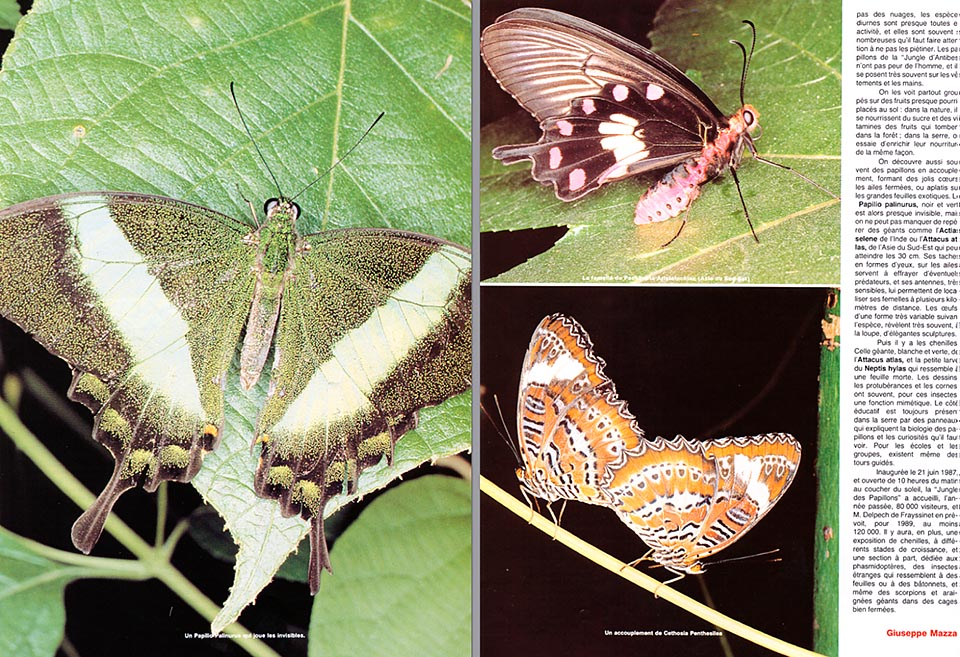

Thus, instead of “pinned jewels”, we can admire butterflies in motion, the matings, when they cross the wings, forming romantic hearts; the disclosing of the eggs, each one with its own typical look, rich of incredible decorative low relief; the caterpillars, often mimetic, authentic leaves-devouring machines, which beat every record of fattening, passing through various moltings; the pupae, frequently enormous, which wait for the metamorphosis under the ground, in cocoons, or suspended, head down, in translucent cases; and the “second birth” of butterflies, when the skin of the chrysalis breaks, giving birth to the adult. The head and the thorax get out first, then the claws and the wings, just sketched, similar to stumps. The insect looks for a support and then hangs down. Then pumps an opal-coloured blood, the hemolymph, in the cavity of the wings, and these extend like sails to the wind. They harden under the sun, become shining, and the butterfly is ready for its light dance of love in the air and the light.

A magical ritual, which repeats since 150 millions of years, since the Jurassic, and which, nowadays, performs in about sixty “zoos for butterflies”, arisen, like mushrooms, all over the world, after the British example. The most renowned, besides the previously cited Butterfly house of Syon Park, are the House of Butterflies of Schlosspark, in Schönbrunn, Vienna; the Jungle of butterflies of Antibes, in France; the Papiliorama of Neûchatel in Switzerland, and the Butterfly house of the zoo of Melbourne in Australia.

In our country, in the Colli Euganei, about 10 kilometres from Padova, at Montegrotto Terme, exists the “Butterfly arc”, a greenhouse of about 700 square metres, rich of a luxuriant tropical forest and more than 140 exotic species. And, everywhere, the philosophy is the same: to help the audience by means of posters, recorded tapes, booklets, and guides, to discover, in a short time, with fun, the incredible world of lepidoptera.

We can learn that the splendid colours on the wings don’t have always a chemical basis, but, quite often, do not exist and come from phenomena of interference and diffraction of the light in thin, transparent, particles, superimposed like crystal tiles; that the drawings and the gaudy contrasts, are useful for mimicry, to frighten the aggressors with false eyes, or to conquer the partner, when at close distance, after that irresistible “love scent”, the pheromons have done the rest; that the nocturnal species develop monstrous antennas, ramified as Christmas trees, capable to detect in the dark, even between the odours of the large city, the presence of a female at two kilometres of distance.

Incredible, but some lepidoptera, even if stumpy and heavy, with short wings, can reach the speed of 60 km per hour; the proboscis of an exotic species, born for sucking the nectar of an orchid with a deep throat, reaches, when spread out, the length of 28 cm; many nocturnal species dispose of sophisticated ear-drums, placed on the thorax and the abdomen, to perceive the ultrasonic shrieks of the bats, their deadly enemies; and the organs of the taste of butterflies are not placed on the head, but on the claws.

That is the reason for which visitors see them often thumping with the feet, the flowers of lantana and of heliotrope, present in all greenhouses, because easy to cultivate and rich of nectar, or the slices of apple, pear, apricot, and orange, rich of vitamins and sugars, offered at the place of the fruits, which, in nature, decompose on the soil of the forests.

Seen that, anyway, they are not enough, every Butterfly house prepares its own blends, which are sprayed with a syringe in the corollas or in big plastic flowers. A solution of honey and sugar, with often additions of dairy produce and glucose.

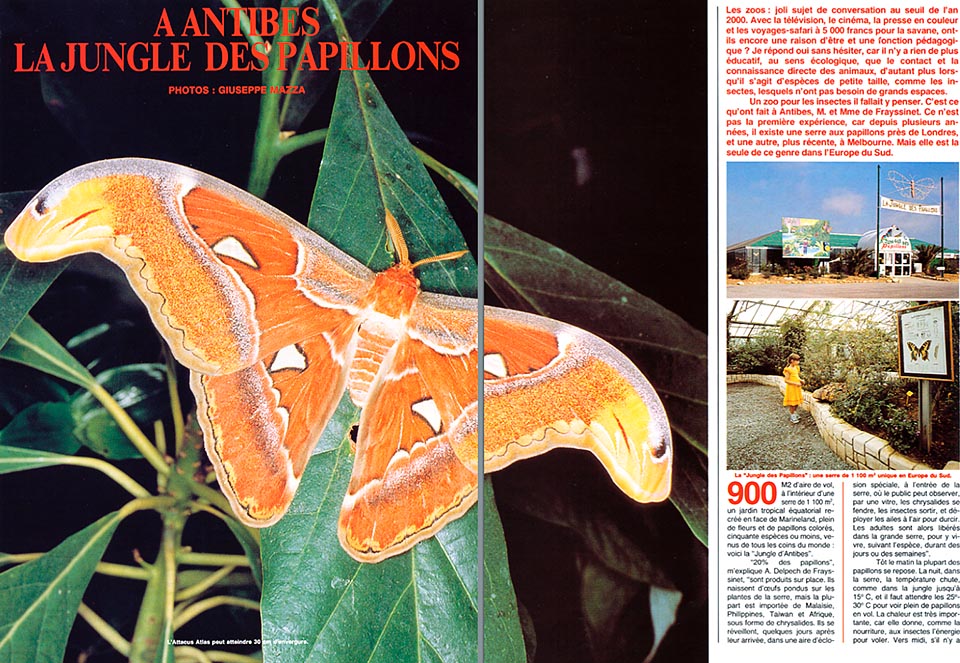

By means of water plays and nebulizers, the humidity is usually maintained around the 70-80%, and the temperature, which during the night tumbles to 15-16 °C, as in the tropics, during the day is set at 25-30 °C. The big size species, like the Atlas moth (Attacus atlas), of South-east Asia, which can reach a length of 30 cm, have in fact the necessity of a lot of energy for flying, and the heat is often an indispensable complement to the food.

So, if we wish to admire many butterflies flying, it’s better to visit the Butterfly houses around noon, when the sun is high in the sky and the temperature reaches the maximum values. Around evening, it’s instead easy to observe the courting, with very long couplings, which can last, frequently, till the following morning.

How long do they live these butterflies? The maximum allowed by nature. But, apart some long-lived species, which touch the three months, the average is of 3-4 weeks, without counting the period as caterpillar. As these ones eat a lot, and are subjected, with the eggs, to the attacks of innumerable groups of parasites, usually only the 10-20% of the butterflies is reproduced on the spot, and they limit themselves to few species without many necessities, with caterpillars spectacular for size, colour, behaviour, or mimetic capabilities. The remainder of guests arrives almost always, by plane, in 24 hours, from breeders in Cameroun, of in Malaysia, under form of chrysalis, or even already adults.

The concentration of the butterflies in the greenhouses is usually of 1-4 per square metre, and the strategies of struggle against diseases differ depending on the seriousness of the institute and on the percentage of butterflies reproduced on the spot.

In Melbourne, for instance, where there is the tendency to show complete reproductive cycles of local species, visitors must disinfect the soles of their shoes in special basins; whilst in the area dedicated to butterflies of the Park Phoenix of Nice, where there are species not important, there is no precaution at all.

It is clear, however, that they cannot use insecticides for destroying small red spiders, lady-birds, aphides, ants and spiders, which threaten the plants, larvae or eggs. They resort, therefore, almost everywhere, to the biological struggle: small Chinese quails, which do not attack the butterflies, but eat striking quantities of insects; crowds of lady-birds, which chase the aphides; and even bacilli, harmless for butterflies, like the Thuringiensis, which infect and destroy the larvae of the parasites.

Visitors, school-children in front, learn in this way from live, that the nature requires a whole vision; that animals, plants, and environment are closely correlated; and that the small, but complicated, ecological system of a Butterfly house, can be the testing place for the ecological problems of the world.

The greenhouse of the zoo of Melbourne

At the zoo of Melbourne, the rain has just stopped. I leave my assistant with the apparatuses at the drink stall, and I make a small passage between the trees. I am hurried to see what has changed since my last visit.

I come across a budding Brachychiton acerifolius, covered only by red flowers, and I slow down to admire the incredible Calothamnus, Melaleuca and Calistemon, rich relatives of our myrtle, which are drying with the wing their scarlet corollas, resembling to fire works , or small brushes to clean inside the bottles.

While I think that at the botanic garden I have photographed ibis and parrots in liberty, that here, in a while, I will have to mount the macro lens for the flowers, I meet on my way a barrier and

a panel. It’s written that nobody can proceed further, but, by this time, the zoo is on the way to close, around there is nobody to ask for, and so, I go ahead all the same, pushed by the professional curiosity.

A great greenhouse, as high as a two floors house, and about thirty metres long, appears to me. It’s closed and I go around it, failing to understand what there is inside. Further on, I discover another one, smaller, with the glasses wet by the condensation.

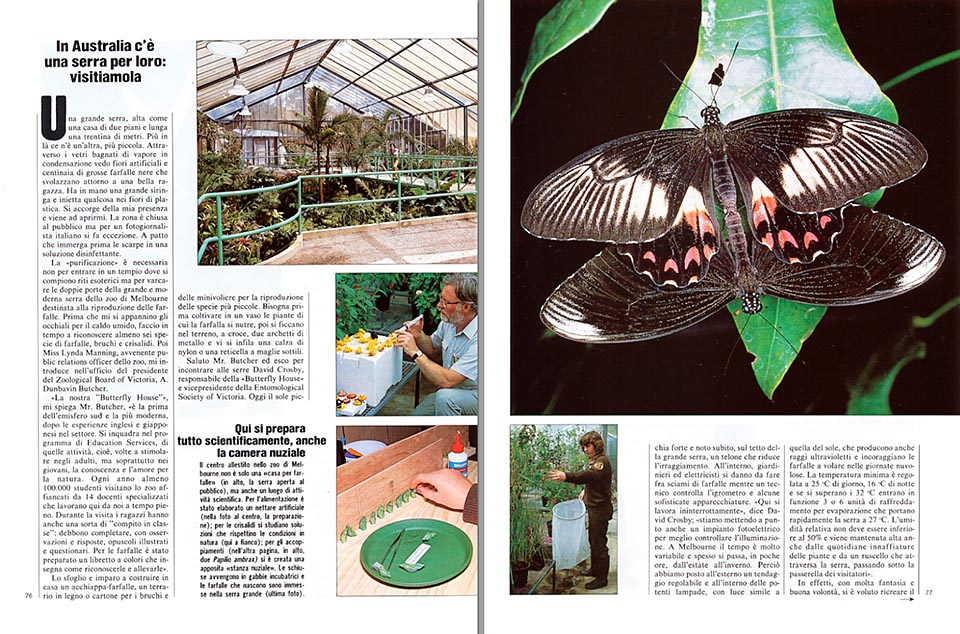

I look inside between the double doors, and I see some artificial flowers and hundreds of black butterflies which flutter around a nice looking girl. She holds a big syringe in her hand and injects something into the plastic flowers. I watch her working, like in a dream, till when she becomes aware of my presence, and, smiling, comes to open the door.

“This area is closed to the public,” she tells me, “and to stay here, you need a special permission.”

I show her my journalist card, and I promise her, that, if she allows me to look around, then I will go away immediately in good order, and I will come back tomorrow, for the photographs, with the required permits.

“OK, OK, but, before, place your feet here, please.” And she obliges me to plunge my shoes in disinfectant solution.

At, last, purified, I cross the double doors of the greenhouse for the reproduction of the butterflies, and like Alice, I find myself, suddenly, in the country of wonders.

Before that my glasses get dimmed because of the wet heat, like in a rainy forest of Queensland, I identify at least six species of butterflies, caterpillars and pupae on small plants in pots.

That is enough for me, to understand that there is material for an article, so, I go back, running, to the hotel, and I phone to the Editor’s office of Natura Oggi, asking of the co-director, Mr. Ruggero Leonardi. Nadia, a charming and romantic editing secretary, connects me with him at once, and Ruggero, after having asked me if I have become crazy, because Rizzoli, in the other side of the world, pays for the call, looks satisfied and convinced.

The following day, Miss Lynda Manning, the pretty Public Relations of the zoo, introduces me in the office of the President of the Zoological Board of Victoria, Mr. A. Dunbavin Butcher, explaining me that this last is a very important person and that I must not take more than five minutes of his precious time.

He receives me, wearing a jacket and tie, in a sumptuous office which holds in subjection, but leaves immediately his writing desk, and we take a seat in a drawing-room corner. I explain him that Natura Oggi, with more of 150.000 copies sold, is the most important European magazine of animals and plants, and I show him the articles I have done, years ago, about Australian fauna.

He is affable, and we sympathize at once. “Our Butterfly house,” he tells me, “is the first in the southern hemisphere, and the most modern, after the British and Japanese experiences done in this field.”

“It fits in the Programme of Education Services, that is, of those activities bound to stimulate in adults, but mainly in young people, the knowledge and love for nature. Each year, at least 100.000 students visit the zoo, accompanied by 14 specialized teachers, who work here with us, at full time. There are seven halls, always crowded, for stages at different levels, and they insist in order that the boys touch skins, horns, bones, and handle, without stressing them, living animals, such as opossums, lizards, and snakes. During the visit, they have also a sort of “school work”: they must complete, with observations and answers, illustrated booklets and questionnaires. For the butterflies, they have prepared a coloured pamphlet which teaches how to identify and breed them.”

I turn its pages, and I learn how to build at home a butterfly catcher, a terrarium in wood or in cardboard for the caterpillars and mini aviaries for the reproduction of the very small species. You have, first, to grow up in a pot the plants the butterfly eats, then they are to be thrust in the soil, cross-like, two metallic small arches and cover with a nylon stocking or a small net with thin meshes.

“We have already some of them ready to be shown to students,” Mr. Butcher goes on, “and at the end of the book, there is, always, a section for observations. They must write down how many eggs have been laid by their butterflies, after how many days they open, how long the caterpillars employ to grow up, and transform in pupae, and how long it lasts, in function of the temperature, the “sleep” of the chrysalises.”

While I thank him and I get out to meet, at the greenhouses, Mr. David Crosby, responsible of the Butterfly house and Vice-President of the Entomological Society of Victoria, I cross Miss Lynda Manning, who looks at me, incredulous, and who probably asks herself still now, how Mr. Butcher could greet me, smiling, after an interview which lasted half an hour.

Today the sun strikes hard, and I notice, at once, on the roof of the big greenhouse, a coarse cloth which reduces the irradiation. Inside, gardeners and electricians work between swarms of butterflies, while a technician checks the hygrometer and some sophisticated apparatuses.

“It will be inaugurated in three weeks,” David Crosby says, coming to meet me, “and we are overhauling a photo electrical unit for a better control of the illumination. At Melbourne, weather is very changeable, and often, we pass, in a few hours, from summer to winter. Therefore, we have placed, outside, a controllable tent and, inside, powerful lamps, with a light similar to that of the sun, which produces also ultra-violet rays, and encourage the butterflies to fly during the cloudy days.

The minimum temperature is settled at 25 °C during the day, and 16 °C, the night, and if it goes over 32 °C, 3 or 6 units of cooling by evaporation, start working and lower quickly the temperature in the greenhouse to 27 °C. Relative humidity must never be less than 50%, and is maintained high also by the daily watering of the plants and by a stream which crosses the greenhouse, under “visitors'” footbridge. Indeed, with a lot of fantasy and good will, we have re-created the scenery of an Australian tropical forest, with some contamination of species introduced from South America.

Bromeliaceae, orchids, ferns and interior plants, mix with bananas, palms and flowery shrubs which attract the butterflies. The result is already very pleasant, and I imagine how it will be in a few years, when the plants will have grown up, and climbers will have covered the masonry walls from where drow out the air conditioning grates.”

“The two thirds of these plants,” David goes on, “are permanent ornaments. The rest, to be renewed periodically, has the function of feeding the butterflies and the caterpillars. Even if the Butterfly house is planned mainly for the exposition to the public, some species, like the Papilio ulysses, and the Ornithoptera priamus, in fact, do reproduce here, because the plants necessary to their caterpillars, cannot be easily cultivated in the support small greenhouses.”

While we move towards these last ones, David explains me that the main one, where yesterday I have met my “fairy with syringe”, is dedicated to the coupling and measures 7 metres per 13. Inside, I notice the usual equipments, and a soft nylon net which covers the glasses.

“It’s used to avoid that the butterflies get injured during their wedding flights”, David says, “and to stimulate them, we have also increased the light from the 1.000 lux of the greenhouse for the public, to 1.500-2.000 lux. The solar spectrum lamps operate from 0600 am. to 0800 pm., and are preceded and followed by the switching on, for 45 minutes, of normal incandescence lamps, with red light, which simulate the dawn and the sunset. The species present now, for the moment, are all Australian, and we have given the priority to those of Queensland, because in nature they have already 4-5 cycles per year, and we succeed in getting 10, by improving the feeding and the habitat.”

“But, what do they eat, and how long to they live?”, I ask, observing a red admiral butterfly, sucking a plastic flower.

“The natural nectar is not sufficient,” he explains to me, and we have been obliged to have recourse to the artificial one, which we spray, every day, with syringes, into the true and plastic flowers. It’s a watery solution of glucose, honey and milk extracts, and, as in nature the taste of the nectar is usually associated to a certain colour, we are doing researches to determine which is the colour butterflies connect more willingly to our mixture.”

“The average life, depending on the species, varies from 2-3 weeks to one month, and, in order to know it exactly, we mark, with colours, upon the birth, the wings of some butterflies.”

I see two attendants coming with small plants of lemon in pot.

“They are required for the Orchard (Papilio aegeus), and the Ambrax (Papilio ambrax). The larvae,” David continues, “eat almost uninterruptedly, and since, in order to impress the public, we keep many species of large size, the consumption of leaves is enormous. The plants cannot be eaten for more than the %, and for recycling them, we have been compelled to prepare a seed-bed with hundreds of pots.”

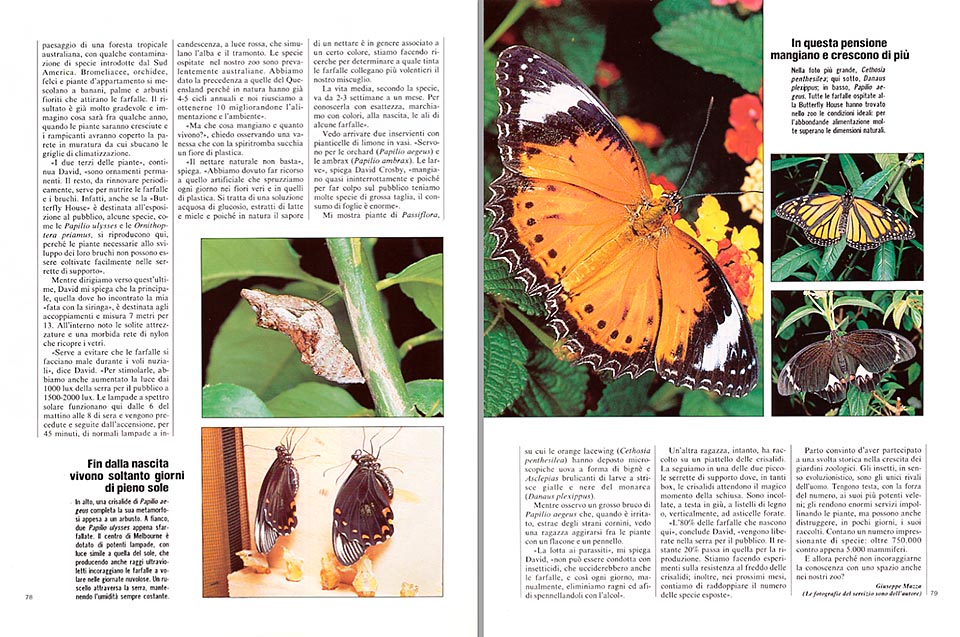

He shows me some passion-flowers, on which the Orange Lacewings (Cethosia penthesilea) have laid microscopical eggs in the shape of a bignet, and some Asclepias, covered by the yellow and black striped larvae of the Monarchs (Danaus plexippus).

“But, these ones, are plants of cabbage, is it?”, I ask rather amazed.

“Sure, and they are useful for the Educational Programme. The large and small whites are an excellent test for the boys: they can find them anywhere, and are very easy to reproduce.”

While I observe a big caterpillar of Papilio aegeus, which, when upset, draws out some odd little horns, I see a girl going about between the plants with a small bottle and a brush.

“The flight against the parasites,” David explains, “cannot be done with insecticides, which would kill also the butterflies, and so, every day, manually, we eliminate spiders and aphides by brushing them with alcohol.”

In the meantime, another girl has collected on a small dish some pupae and we follow her in one of the small support greenhouses, where, in many chambers, the chrysalis wait for the magic moment of the opening. They are stuck, head down, to small wooden stripes, or, vertically, to small holed poles. Lepidoptera are, in fact, ole-metabolic insects, that is, with a complete metamorphosis, which, before reaching the adult stage, have to go through the phases of egg, caterpillar, or larva, and pupa or chrysalis.

“The 80% of butterflies born here,” David concludes, “are set free in the greenhouse for the public, and the remaining 20% go to the one for the reproduction. We are performing experiments on the resistance to the cold of the pupae and within mid 1986 we intend to double the species being exposed.”

Thanking, I assure him that I will come back to see the progresses done, and I leave, convinced of having participated to an historical turning in the development of zoological gardens.

Insects, evolutionally speaking, are the only rivals of man. They stand up to, with the force of their number, to the strongest poisons made by man, tender him enormous services, pollinating the plants, but they can also destroy, in a few days, his crops. They count more than 500.000 species, against only 5.000 mammals. And then, why not to encourage their knowledge with some room also in our zoos?

NATURA OGGI – 1986

→ For general notions about the Lepidoptera please click here.

→ To appreciate the biodiversity within the BUTTERFLIES please click here.