Family : Scolopacidae

Text © Dr. Gianfranco Colombo

English translation by Mario Beltramini

The Gallinago gallinago is practically cosmopolitan, missing only in Australia and in the Pacific islands © Gianfranco Colombo

The Common snipe (Gallinago gallinago Linnaeus, 1758) belongs to the order of the Charadriiformes and to the family of the Scolopacidae.

The common snipe has entered by force and since always the hunting jargon, as the archetype of the sacrificial victim of a good shooter. In the stories of each hunter is present the memory of an adventure having as main character this small limicolous, of the pointing of his faithful dog setter and of the successful shot.

Yes, because the story of the beautiful shot recurs not so much for reminding that the flight of this bird is so fast, darting and difficult that succeeding in the aim is a real feat. Also the composer Puccini was talking of it quite often when, back from the “Massaciuccoli marshes” reminded to his friends the particularity of this hunting.

The common snipe is a species that can be hunted in almost all its range and the number of the culls is considerable, but the good prolificacy and the remote places of nidification, provide a major guarantee about the stability of the number of the populations.

Also the literature has been involved, so much that Tolstoj in Anna Karenina talks of it as the hunting preferred by Levin. In the ornithological tradition of the nineteenth century well described by Louis Figuier in some of his works, this bird was described as royal snipe distinguishing it from its similar Jack snipe (Lymnocryptes minimum) and the Great snipe (Gallinago media).

Actually a common characteristic of the snipes in their tactics of defense, is that to stay crouched and hidden into the grass and lift off only when we are very close, just a stroll, as if it was really deaf. The fright of the surprise, the sound of the whirring wings, the incredible speedy starting, the wandering flight and the famous smacking kiss, by sure do not facilitate the approach with this bird.

With 75 mm of length, it has the proportionally longest beak among all Italian birds © Gianfranco Colombo

40 cm wingspan and weight varying, depending on the seasons, between 80-150 g © Colombo

Many kids of those sites reproduce as a joke this bleat by inserting some feathers of the tail of the common snipes in a cork and then rotating it vortically attached to a wire. The vibration of the feathers on the friction with the air causes the same sound effect.

But the main term and often repeated in old dialects by many European peoples is the onomatopoeic reference of the fateful kiss emitted when leaving that sounds like a curt and acute “sgnep”. Sgneppa in Italian, Schnepfe in German, snipe in English, sneppe in Danish, snappa in Swedish, snipa in Icelandic. But also the Italian common name of beccaccino, referred to its beak, an attribute that surely doesn’t go unnoticed due to its length, is repeated in the common names given nowadays to this bird.

Bekassine in German, Bécassine des marais in French, Agachadiza común in Spanish and Common snipe in English.

The etymology of the scientific name Gallinago, repeated in the name of the genus as well as in that of the species, comes from the Latin “gallina” and “ago- ” = resembling a hen, for the position, similar to that of a common broody hen it assumes when staying on the ground.

Finally, an explanation to the two synonyms Capella and Scolopax, two genera to which had been alternatively assigned this bird previously. In Latin, the term “capella” is the name give to the female of the goat whilst, always in Latin, the term “Scolopax-Scolopaceus” means striped, streaked.

Zoogeography

The common snipe is a typical inhabitant of the world, being absent only in Australia and in the Pacific islands. It nidifies in the temperate cold belt of the boreal continents to then go down to all latitudes during the migrations.

It lives in backwaters, rice fields and marshy meadows with muddy bottom where to introduce their very long beak looking for earthworms and aquartic molluscs © Gianfranco Colombo

Three subspecies have been classified, the Gallinago gallinago faeroensis, the Gallinago gallinago gallinago and the Gallinago gallinago delicata, this last purely American and recently considered by many as a species on its own, under the common name of Wilson’s snipe. It nidifies from Alaska through Canada, to Europe and Asia up to Siberia and in the underlying temperate belt with peaks touching south a good part of the North-American continent, Central Europe with instances in the north of the Iberian Peninsula and with good presences in Austria, in Ukraine and in China. In Italy, the cases of nidification have been very rare and not always positive.

Here it is, similar as the Latin name says to a small hen, exploring carefully the bottom searching its tiny preys © Gianfranco Colombo

In the wintering areas it forms groups at times numerous, in particular when it finds environments with a good availability of food and of water not subjected to frosting.

I took one more snail … and you did you find it? Seems to say this cheery common snipe to its companion still busy on the right © Gianfranco Colombo

Typical was the presence of this bird in the Lombardy water meadows that at times were able to maintain several populations of common snipes during the whole winter even if in conditions that otherwise would have resulted unlivable for these bird.

Rich of nervous terminals to locate and catch the preys in the mud, the tip of the beak is very flexible and can move, free from the rest, like a tweezers © Gianfranco Colombo

Nevertheless, the populations of the northernmost areas have the tendency to move quite soon on the autumn calendar and already by the end of the month of August – early September we can assist to a first wave of migrants invading Central Europe, Italy included.

This phase is remembered in the hunting calendar as the arrival of the “September ones”, the first offshoots of the real autumnal migration.

In the wintering areas it is however scattered in every suitable location, even alone or in very few individuals, thus becoming common on very vast areas.

In the tropics it overlaps to the populations of local species creating quite remarkable difficulties of identifications.

Well known is the case of the species of the African snipe (Gallinago nigripennis) so much similar to the European that it cannot be distinguished if not having a specimen in own hands.

Ecology-Habitat

To describe unequivocally the environment frequented by the common snipe it is sufficient to go back to Figuier’s words. “The hunter of snipes does not have in view the horrible rheumatism that come to sit close to him in an age when the men are still robust? But seen that usually the rheumatisms come only late, we do not think at all, as long as we are young, except to regret later the fatigues suffered”.

The common snipes live in humid environments, swampy, rich of backwater, rice fields and marshy meadows with muddy bottom where to set their very long beak looking for earthworms and aquatic mollusks. It absolutely avoids the woods and the densely wooded areas but loves swamps partially disseminated with low shrubs, marshy willow groves or sparse thickets with wide open areas.

Typical so-called bleat posture. Especially in the fast court flights, common snipe can in fact vibrate the outer feathers of the tail, very elastic, imitating the sheep bleating © Gianfranco Colombo

During the migration it can be accidentally found even in stubbles of corn, in stable meadows or along the irrigation ditches but it is only a temporary situation seen that then in the late evening gathers in previously set places where it spends the night. An inevitable event that sees converging at dusk all the population of the surrounding area.

Morpho-physiology

Like all scolopacids, the livery of the common snipe is very mimetic and is composed by colours that easily confuse it with the habitat where it lives.

The basic colour of the upper part of the body is dark brown crossed by black and white lines, by disorderly and speckled streaks and by spread chiaroscuro dotting.

The head is crossed by longitudinal black lines that reach the nape and end mixing with the drawings of the back.

The chest and the sides are grooved but reveal the pale cream background that widens on the abdomen to become completely white.

The legs, somewhat short for a limicolous, are greenish whilst the very long beak is of dark flesh green colour.

The tail is of hazelnut colour slightly barred, with calamus reinforced in the lateral feathers.

Characteristic of the scolopacids are the eyes significantly moved backwards and a little higher on the skull, that allow an ampler field of view.

The distinction with other species that share some parts of the territory is not an easy thing.

Practically indistinguishable from the common snipe are the Pin-tailed snipe (Gallinago stenura) and the eastern Asian Swinhoe’s snipe (Gallinago megala) two species that share part of the range and considered the difficult of the approach, often these presences go unnoticed also in locations where they would appear as pleasant exceptions.

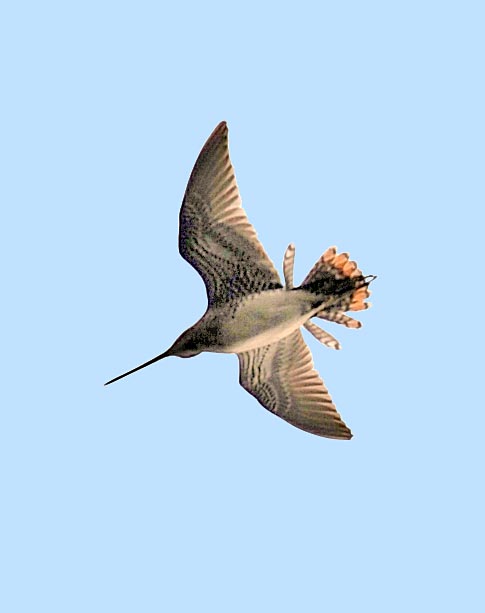

No less famous, in similar cases, is the suicidal dive at breakneck speed, so rapid to render it almost invisible, with lateral move to dampen the landing that leads it at about 3-4 m from the perpendicular © Gianfranco Colombo

Finally, it is good to remember, in particular in Europe, the presence of other two species very similar but of easier recognition with whom the common snipe shares the wintering sites.

The Great snipe (Gallinago media) that is more barred on the sides and with the beak slightly shorter and the Jack snipe (Lymnocryptes minimus) considerably smaller and a much shorter beak.

The common snipe is about 28 cm long , of which more than one quarter given by the beak, a wingspan of about 40 cm and a weight, depending on the seasons, that varies between 80 and 150 g.

With even 75 mm of length, the common snipe is by far the bird with the proportionally longer beak among all our birds.

Ethology-Reproductive Biology

The flight of the common snipe is frantic during the departure and the arrival. We have already talked about the sprint start and of the acceleration that sees it whizzing at full speed since the first metres but even more particular is the modality of descent to the soil.

The common snipe gets down from great height towards the soil in a perpendicular dive, at full speed as if it were trying to commit suicide, just that when at a pair of metres from it, in a so much rapid way to appear invisible, opens the wings and lands running laterally on the ground some metres far in order to break the fall.

Practically, we see it coming down at that point like a lead but we find it aside, 3-4 metres far. This characteristic is shown also during the courting flight during which it emits the famous bleat, when getting down from a remarkable height, twisted on itself in a suicidal dive, with the tail opened like a fan and reaching the soil with the same modalities.

The nest of common snipe is a simple depression among grass. The chicks, here one recently born, disperse quickly, surveyed by the adults till when they learn flying © Gianfranco Colombo

The common snipe nourishes of earthworms, of small snails, of mollusks, of crustaceans, of small coleopterans and also of seeds sprouted in the water and of aquatic plants.

The research is done by introducing the very long beak into the mud, testing the bottom and finding the preys with the tip that is mobile and equipped with a very sensitive part.

The reproductive season is announced by the continuous bleat emitted by the birds in flight to conquer the female and the nidification territory. Being a very discernible and distinct sound and considered the high number of presences of this bird in the northern continent areas, is conceivable the turmoil that pervades those places in this period.

When then it lands, it does not stop in emitting sounds and goes on in croaking staying on a boulder or on a low wall or on a rise in the ground or even on the roof of low dwellings when available.

It is therefore a bird that strongly announces its presence and it is consequently impossible not to see it.

The nest of the common snipe is a simple depression in the soil and the eggs are laid directly on it without addition of material.

It is a nest well hidden by the tufts of grass over it and that creates a niche well covered and hardly visible when passing close to it. Often it is placed at the foot of low shrubs and dwarf willows, creating a double cover that renders it absolutely invisible.

The ground chosen is boggy or very close to the water, but the nest is placed on a slight rise of the soil to avoid possible and fatal floodings. It lays four greenish eggs, of a very oval shape, marked strongly by darker and irregular spots that accentuate in the ample part of the egg. The brooding done only by the female lasts 21 days and the chicks come to life covered by a thick mimetic down similar to that of the adults, that renders them practically invisible with the surrounding environment.

When one year old they are already able to reproduce. Despite hunting, the common snipe does not seem endangered. Only in Europe there are presently about 1.000.000 nidifying couples © Gianfranco Colombo

Synonyms

Capella gallinago Linnaeus, 1758; Scolopax gallinago Linnaeus, 1758.

→ For general information about the Charadriiformes please click here.

→ To appreciate the biodiversity within the CHARADRIIFORMES please click here.