And the fish became gold. The fascinating true story of an invented animal. Everything on the goldfish. Spectacular photos of mating and hatching of the eggs.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

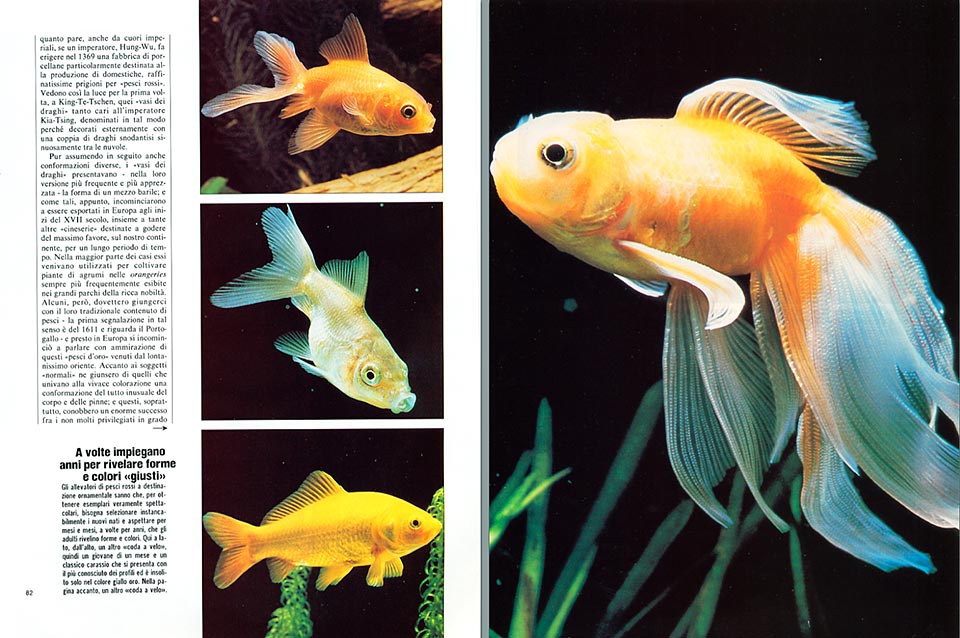

Anybody can easily recognize, in springtime, the adult female of a goldfish. It’s full of eggs, and, seen frontally, looks more roundish, more swollen than the males, which exhibit, moreover, on the opercula and on the hard ray of the pectoral fin, some horny protuberances, “pearls” to persuade, with exciting caresses or rough scratchings, the females to lay.

With the idea to breed them one day, and mainly to fertilize a 12 square metres philodendron, which lives, since years, in symbiosis with two 400 litres aquaria, I had purchased, four years ago, three little goldfish, “three tails”, as my daughters say, three hungry musketeers, always ready to fight for a small piece of meat or a grain of boiled rice, which, later, should have revealed us their sex, and from which I hoped to isolate a couple.

The darkest, almost black, had been christened Nero, then there were Monsieur Rose, after the name of our neighbour of the upper floor, with an orange-pinky livery, and Red Queen, with some little black dots, which was growing up at sight, eating everything before the others, with grace and regal authority.

Nero died one day, suddenly, of an indigestion, or of a stroke, and since then, Monsieur Rose, which in the meantime, growing up, had been found to be a madame, started quarrelling with Queen.

And we had to separate them in two pools, with shred find, after a vigorous disinfection with methylene blue.

Months elapsed, and on last April, Queen, even if being alone, covered the Java moss of the aquarium, with hundreds of eggs, repeating the operation in May.

Strange thing, it did not eat them, as usually goldfish do, but surveyed them, with the zeal of a cichlid, deceived by the fact that nothing was arising.

“Come on, daddy, find her a husband!”, my daughters were repeating in choir, and so came the idea of a reportage: to go to Bologna, where, since more than 100 years, goldfish are nursed, to photograph a model fish-breeding, and come back with some adult males for Queen and some fecundated eggs. Just to save the service, in case, who knows, the pretenders should not like Queen.

I phone Nerio Brintazzoli, an old friend of the Euraquarium, the Italian wholesale dealer of exotic fishes, I leave the daughters to the ultra eighty years old grandparents, and, accompanied by my wife, after 9 years that, due to the children, I rely on other assistants, we reach Bologna.

For South Africa, Australia or the round-the-world tour, it’s always easy to find “volunteers”, biology students or naturalists who can stay away even for a full month, but goldfish in Bologna, in May, do not attract anyone.

“The breeding of Carassius auratus in Emilia”, Nerio Brintazzoli explains at once to me, “originated during the second half of the nineteenth century, along with the cultivation of hemp.”

Countrymen were cutting it in September, and it was going to the rettery, for the extraction of the fibres. But, once the cycle was completed, these ponds, very rich of plankton, were practically left not utilized. The long process of decomposition had created billions of microscopical algae, infusorians, daphnia, and other crustaceans ideal for the “first ten months diet” of goldfish, and the only thing to be done, was to introduce, in May-April, the sires, two males for each female, to lay the snares, by the end of August, on thousands of sparkling little fishes, destined to a remunerative expanding market.

Aquariology was moving the first paces, and the goldfish, sturdy, fit also for cold waters, and poor of oxygen, was the ideal guinea-pig. Furthermore, it was not expensive at all, and this, still now, is his only shortcoming, the reason which often makes them martyrs for the “torture of the round bottle”, and does not allow producers and dealers to care them as they should.

Less than 200 Liras at the origin, and parasites such as the Argulus foliaceus, or the Lernaea (to be removed with very diluted products for dogs), are often familiar. They suck the blood, the wounds get infected, and when the poor, very resistant goldfish, after some weeks of almost fast in the crowded pools of the dealers, arrives in the domestic aquarium, is, quite often, in poor conditions.

“About the death of a goldfish”, Nerio comments, while we reach a breeding pilot centre, “there would be often material for writing a degree thesis.”

Mrs. Anna Maria Pancaldi, manager, shows us all the secrets of the profession. Huge basins with plants for the oxygenation for the warm periods, stabling pools, for disinfecting and selecting the fishes before placing them in the market, a cabinet for analysis, and even a small cannon loaded to blank, to frighten the herons and other predatory birds.

There is not much to do against coronellas and ringed snakes, and while my wife stumbles in an enormous specimen, just sliced by a mowing-machine, we reach through a path, the pond where the pairings happen.

In a corner they have thrown some hay to steep, and females come every morning to lay, pursued by the males. We can have a glimpse of them just for a moment, while they bend their back out of the water, and disappear with a splash. Impossible to photograph them, but we pick up the eggs, and after having placed them in small sacks with 2/3 of oxygen, we close them in a thermic box, close to Regina’s husbands.

They reach Monte Carlo, during the evening. The males go into 400 litres pools with two wonderful females, and the eggs in a small, 20 litres aquarium, well oxygenated, with the company of a couple of ears to produce infusorians.

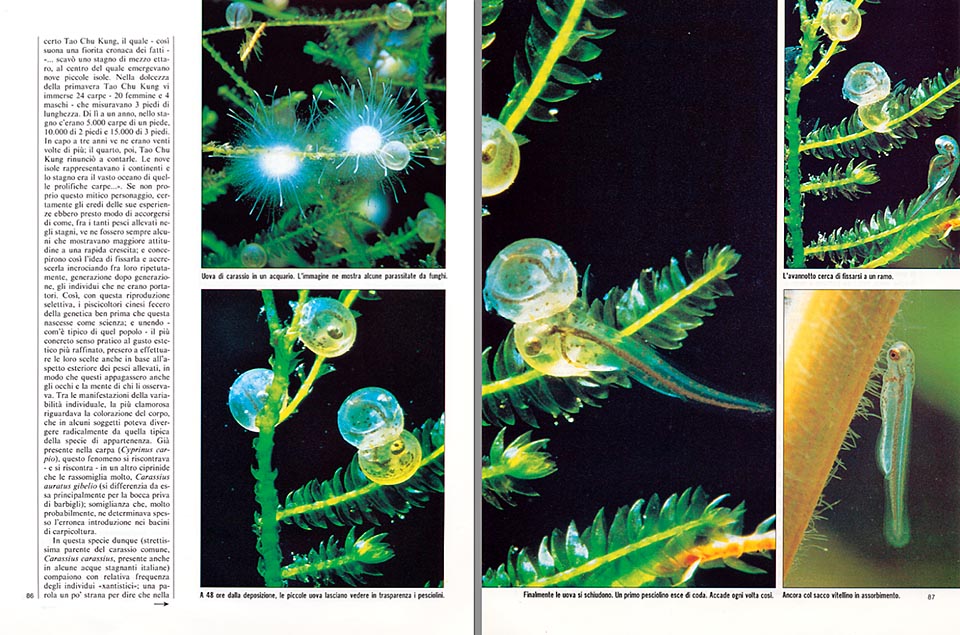

The following morning, through a special lens which magnifies the subject on the film, to 10 times, I notice that the eggs by now contain some embryos, and while I regret for not having photographed them at once, in order to immortalize the full cycle, I am called by my daughters.

In my working room, Regina is mating. She has chosen Monegasque, a young comet goldfish, half white, half red, like the flag of the Principality, and ignores the two wonderful marbled goldfish, which pursue Regina awkwardly, bright as kaleidoscopes.

Monegasque is more rapid, and disappears, embraced by Regina. The eggs fall by hundreds. Will they be fecund?

In any case, I isolate them, with the usual Java moss, in another small aquarium.

And this time, I photograph them immediately: they are transparent, with, in the centre, a yolk with nacreous reflects, perfectly spherical.

By the evening, it has already changed of shape, and after two days, the fry are well visible, with dark eyes and the tail refolded on the head.

The small pool with the eggs from Bologna is swarming of new born, and my eggs, those filmed in all the phases and which, luckily, have not yet been attacked by worms, might open at every time.

After hours and hours of exhausting wait, one of the four fry gives a start and gets out by the tail, with a leap.

I remain stuck to the view-finder, but still three quarters of an hour elapse. At last, the moment has come: the customary tail raises from a shell, and then we can see the yolk sac, and the head of the new born which falls down in a moment which seems an eternity.

I hold my breath and I shoot a photo after the other, with the most probable diaphragm. The fry assemble, slowly, on the glass of the aquarium. They don’t move and twinkle as stars on a blue sky. They will be a thousand, perhaps more, and they rest for hours, after the labour of the delivery.

The water of the small pool is rich of infusorians, swarming with limneas and Planorbarius, which eat voraciously the putrefying ears, but it’s time to take them out and place, on a side, some support cultures: concentrations of paramecia and rotifers, obtained with the method of the bottle and the cotton plug, and small vases of microscopic small eels, which grow up in a mixture of corn flakes, milk, and yeast.

Also the yolk of a boiled egg, reduced to powder with the fingers, encounters immediately the favour of the young.

I have rescued hundreds of them, for the puddles of water in the gardens of friends of Monte Carlo and surroundings, but the most handsome, the “three tails”, (this form is recessive and also in the unions between goldfish, the 80% of the kids are normal at birth), did remain in the aquarium.

In three months, they have reached the size of 2 cm; they are still hazel coloured, but, quite soon, slowly, they will assume the splendid livery of the species.

NATURA OGGI – 1989

→ To appreciate the biodiversity within the Osteichthyes, the BONY FISH, please click here.