Text © Prof. Pietro Pavone

English translation by Mario Beltramini

Vanda cerulea. Orchids are one of the richest and more diffused families in the vegetable kingdom. The flower is formed by 3 sepals, one up and two on the sides down, 2 often very similar petals, and labellum in centre near the pollinodes column, two sacs full of pollen grains they entrust to the pronubes with incredible tricks © G. Mazza

The family of the Orchidaceae Juss.,1789, gets its name from the genus Orchis (from the Greek ὄρχις = testicle, due to the spherical and paired tuberiform roots that appear in some species). It was Theophrastus (371-287 BC) to call in this way these plants as he was convinced that the tuberized roots had curative properties against impotence. As a matter of fact, the orchid in the past was considered as an aphrodisiac plant and a harbinger of fertility.

The two roots, that have been interpreted as a “tuberized rhizome”, are separate and represent a perfect system of survival of the plant. The vegetative part gets its nourishment alternatively from one tuber at the time, giving the possibility to the other to store energy resources and then, later on, to render them available, in particular when are exhausted those necessary for the heavy engagement for flowering and for the fruitification of the many seeds.

In order from left, Bulbophyllum lobbii, Dendrobium nindii, Epidendrum ciliare and Pleurothallis aspergillum. These 4 genera are surely the richest in the family. The genus Bulbophyllum has the record with 1,867 species. Then, the genera Dendrobium with 1,509, Epidendrum with 1,413, and Pleurothallis with 551 species © Giuseppe Mazza

The family belongs to the Monocotyledons; it is one of the most diffused and richest in the vegetable kingdom and contends supremacy with the dicotyledon Asteraceae. The Orchidaceae include more than 28,000 species distributed in about 763 genera that correspond to about 10% of all known seed plants (Spermatophytes). The richest genera are Bulbophyllum with 1,867 species, Epidendrum with 1,880 species, Dendrobium with 1,509 species and Pleurothallis with 551 species.

In Europe and in the Mediterranean Basin are reported more than 300 species of Orchidaceae whilst the spontaneous Italian flora amounts to about 180 of them. From the introduction of the tropical species in the cultivations starting from the 19th century, the horticulturists have produced more than 100,000 hybrids and cultivars.

Coelogyne swaniana, Dendrobium farmeri and Isabelia pulchella. Most orchids are epiphytic as growing anchored to trees or shrubs © Giuseppe Mazza

The species of the family are easily recognized from the other plants because of some very evident characters: the bilateral symmetry of the flower (zygomorphic flowers), the resupination of the flower through a 180° twisting of its elements, the merged stamens and the carpels, and the very small seeds.

Most of the species of orchids are epiphyte, that is, growing anchored to trees or shrubs, in particular the tropical and subtropical ones. Other species, those of the temperate environments, are terricolous and are found in habitats like prairies and forests. Some species, such as Angraecum sororium Schltr., Dendrobium kingianum Bidwill ex Lindl., Paphiopedilum godefroyae (God.-Leb.) Stein, P. armeniacum S.C.Chen & F.Y.Liu, are lithophytes, that is, growing on rocks.

The orchids are perennial grasses, without permanent woody structure and may have a monopodial or sympodial growth.

Others, like Paphiopedilum micranthum, Barkeria halbingeri and Phalaenopsis pulcherrima are lithophyte as growing on the rocks © Giuseppe Mazza

In the monopodial growth, the stem sprouts from one single bud, the leaves form every year from the apex and the stem elongates consequently. The stem of these ones, with monopodial growth, can reach several metres of length, such as, for instance, in Vanda (V. dearei Rchb.f.) and in Vanilla (V. polylepis Summerh.).

In the sympodial growth, part of the plant is newly formed and another, the rear one, is older. The adjacent buds, when they reach a certain dimension, bloom and then stop growing. In the epiphyte species the growth occurs laterally instead of vertically. This allows to follow the surface of the support on which it grows. The new buds, with their own leaves and roots, sprout close to those of the previous year, like in the genus Cattleya, and elongate the rhizome.

Aerides lawrenceae and Vanda limbata are monopodial orchids as the stem starts from one single bud developing on only one vertical axis, at times very long © G. Mazza

Bulbophyllum nummularioides with tiny flowers and pseudobulbs where stores water and food for the difficult moments. This orchid instead is sympodial, as, growing, develops horizontally, on the sides, from buds under the apical. It’s many epiphytes case, looking for a large stem support in the branches © Giuseppe Mazza

In the warm and constantly humid climates, many terricolous orchids do not have the necessity to have pseudobulbs; conversely, these are necessary in the epiphytic species that, having to grow on a support, enlarge the basal part of the stem storing carbohydrates and water, in order to resist during the periods of lack of humidity and of nutrients.

As a matter of fact, the epiphytic orchids hold modified aerial roots that at times may be even some metres long. In the oldest parts of the roots is present a sort of spongy epidermis called velamen, that has the function of absorbing the humidity of the air. The velamen is formed by dead cells and can be of grey-silvery, white or brown colour. Under it stands the ectoderm formed by one layer of cells with thickened walls called transfusional cells (or tilosomes) followed by the conducting elements of the wood (xilems) and of the libro (phloem).

The variously sized pseudobulbs are smooth or have longitudinal grooves. In Grammatophyllum speciosum, the biggest world orchid, they reach 3 m © Giuseppe Mazza

Several epiphytes become completely dormant for months and have the acid metabolism of the Crassulaceae (CAM) (Crassulacean Acid Metabolism), that presents the absorption of CO2 during the night and the photosynthesis, with the Calvin Cycle, during the day keeping closed the stomatic openings in order to reduce the loss of water through the transpiration.

The cells of the epidermis of the root, in order to firmly grasp the support on which to grow, form at right angles in respect to the axis of the root. The nutrients necessary to the epiphytic species come from powders, organic debris, animal droppings and other substances that gather on the surfaces of support.

The surface of the pseudobulbs is smooth with longitudinal grooves and its size is very variable.

Chiloschista lunifera with aerial roots. In some species they are very long. At times they do the photosynthesis, and the oldest part has a silver gray, white or brown spongy coat, the velamen, that absorbs air humidity © G. Mazza

In some species of Bulbophyllum (B. pecten-veneris Seidenf., and B. speciosum Schltr.), the single pseudobulbs are small, of spherical shape with one or two leaves at their apex, whilst in the largest orchid in the world, the famous Grammatophyllum speciosum Blume (Giant Orchid), can reach three metres. Some species of Dendrobium (D. carronii Lavarack & P.J. Cribb, D. delacourii Guillaumin, D. mutabile (Blume) Lindl.) have pseudobulbs, similar to canes, with short or rounded leaves over all their length; other orchids have hidden or very small pseudobulbs, completely enclosed in the leaves. When ageing, the pseudobulb loses the leaves and becomes dormant though furnishing food to the plant until its death. Normally, it may live up to five years.

The Orchidaceae usually have simple leaves with parallel veins, excepting some Vanilloideae whose veins are reticulated. The leaves can be ovate or lanceolate and have variable dimensions on the same plant. Usually, the morphology of the leaves adapts to the characteristics of the habitat.

The heliophilous species growing in open areas, or the species of occasionally dry sites, have coriaceous leaves and the laminae are covered by a protective waxy cuticle. The sciaphilous species, that love the shade, do have long and thin leaves.

In most orchids the leaves are perennial, that is living several years, whilst in few others, especially those with leaves equipped with ribs (plicate leaves), like in the genus Catasetum, fall annually and new ones take form alongwith the new pseudobulbs.

Some genera like Aphyllorchis, Taeniophyllum and Dendrophylax (among which D. lindenii Benth. ex Rolfe known as “Ghost orchid”) have roots provided of chlorophyll for the photosynthesis and have no leaves. Other ones, like those of the genus Corallorhiza, have roots in fungal symbiosis where the fungus issues the sugars necessary for the growth of the orchid, acting as nutritional bridge between this one and the plants doing the photosynthesis.

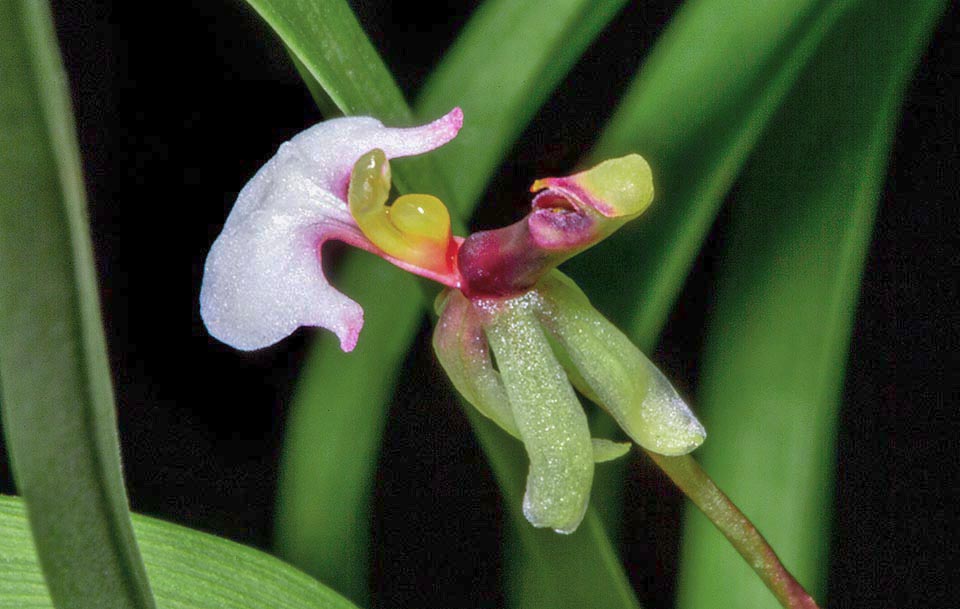

The flowers of the Orchidaceae are very complex to adapt to the pollination done by very specific and particular insects. Like most flowers of the Monocotyledons, their perianth is formed by an external verticil of 3 petaloid pieces, almost always free, and a second inner verticil of which 2 free elements are placed laterally and one rear element that, by rotation (resupination) of 180°, moves forward with a broadened shape in order to be a platform for the pollinators, called labellum that often extends in a nectariferous spur.

The orchid flowers are very complex, at times pitiless, to adapt pollination by very specific and particular insects. Can be solitary, like Bulbophyllum dearie (top left), or united in spike inflorescences like Pinalia multiflora (top right), racemose like Habenaria medusa (down left), or panicle like Renanthera philippinensis (down right) © Giuseppe Mazza

The labellum can be entire or divided in 2 or 3 hems. In Malaxis the flower undergoes a 360° rotation, consequently the floral elements get back to the starting point.

The resupination is a derived character (apomorphy) exclusive to the only phyletic line of the Orchidaceae and that has interested also the fertile part of the flower. Some orchids have lost secondarily this resupination, like, for instance, Epidendrum secundum Jacq.

The free sepals are found in Cattleya, the two lower ones are united and the lip assumes the shape of a shoe in Paphiopedilum (Venus slipper); all sepals are merged in Masdevallia and can be expanded or joined together thus getting a tubular shape.

The orchids lateral sepals, usually free, may unite to form with the labellum fanciful shoe-shaped structures to trap the insects, as in this Paphiliopedilum armeniacum (down left), or merge to the dorsal sepal to form a tube expanded on the three sides or completely closed like in Masdevallia mendozae (down right) © Giuseppe Mazza

The flowers with an abnormal number of petals or lips (peloric flowers) form by anomalous genic expression usually induced by environmental stress.

The flowers can be solitary or grouped in spike, raceme or panicle inflorescences, located at the extremity of the stem with sympodial growth in the terricolous orchids, whilst they form at the axilla of the leaves in the epiphyte forms. The floral stem can be basal, that is produced by the tuber, like in Cymbidium; apical, if formed at the apex of the main stem such as in Cattleya, or axillary at the axilla of a leaf, like in Vanda.

The primitively three stamens have remained as such only in the genus Neuwiedia. With the evolution the stamens reduce to two, the central one being sterile and reduced to staminode in the Cypripedioideae.

Colour apart, the Cephalanthera rubra flowers evoke with misleading form, those of the bellflowers, thus exploiting their pronubes © Giuseppe Mazza

All other species of the family Orchidaceae have only one central stamen, the other two are reduced to staminodes. The filaments of the stamens are always fused (adnate) to the style forming a cylindrical structure called gynostemium or column. The fusion is total in the Orchidoideae and in the Epidendroideae, partial in the Apostasioideae and in the Vanilloideae. The stigma is asymmetric having the lobes folded towards the centre of the flower, on the bottom of the column.

The pollinic granules are freed one by one in the Apostasioideae, Cypripedioideae and Vanilloideae whilst in the other subfamilies, which are the majority, the anther carries two pollinia (also called pollinodes, in Latin pollinia) formed by globular waxy (at times floury) aggregates of pollen supported by a filamentous structure called caudicle (i.e. Dactylorhiza, Habenaria) at whose base stands a viscous gland called retinaculum or viscidium that serves to stick the pollen to the body of the pollinators.

In order from left, Ophrys insectifera, Ophrys apifera and Ophrys scolopax. These genus orchids do even better imitating the shape, pattern and odour of some insects’ females. Males, thinking they rest on a stem, come for mating but it is impossible so leave deceived to an analogous flower with their smelly load © Giuseppe Mazza

In the orchids producing pollinia, the pollinator enters the flower, touches the viscidium, that sticks to its body, usually on the head or on the abdomen and extracts the pollinium connected to it, then when the pollinator rests on another flower of the same species, the pollinator adheres to the stigma of the latter pollinating the same.

In the orchids with single anther stands the rostellum, a thin extension involved in the complex mechanism of the pollination. The gynoecium has three carpels united at the margins (tricarpellate ovary), forming one only cavity, at whose edges stick the ovules (parietal placentation) excepting the Apostasioideae: these have an axillary placentation where the ovules stick to the central placental sutures forming a column.

Where pollinators miss, some orchids like Neottia nidus-avis self-pollinate. The caudicles dry up and the pollinodes fall straight on the stigma © Giuseppe Mazza

The orchids have developed systems of zoogamous pollination highly specialized with the risk of missed visit whereby the flowers remain receptive for very long periods and every time the pollination occurs, thousands of ovules can be fecundated.

Basically, there are three types of calls that are real deceptions: visual, tactile and olfactive. The visual trick is done with the transformation of the labellum in shapes and colours that perfectly imitate the abdomen of the female individuals of the pollinating insects. In fact, the male believing to find the female, rests on the flower mistaking it for its sexual partner. So, it begins the courting movements and tries to couple with the flower (pseudo copula). In the meantime, the insect hits with its head the two pollen masses (pollinia) that adhere to it. Not satisfied and desperately looking for the female, it moves to another flower fulfilling the pollination.

Where cold comes suddenly and the corolla has not even time to open, in orchids like Limodorum abortivum fecundation may occur also with closed flower © G. Mazza

In the genus Ophrys we observe very sophisticated mechanisms for calling the pollinators. At times the pollination is so extreme that it attracts only one species of insect, or at most, two and if the pollinator is missing, the vegetal species risks extinction. But some, as, for instance, Ophrys apifera Huds., if pollinators are absent, adopts the self-fertilization (autogamy); in fact, the long caudicles supporting the pollinodes, drying-up, bend downwards eventually reaching the stigmatic cavity that, in this way, is pollinated.

Epidendrum radicans Pav. ex Lindl., an orchid that does not produce any food reward, has transformed its flower to render it similar (visual trick), to that of various plants of other families that, instead, produce nectar. The pollinating insects are in this way deceived and, laying on them, provide the pollination of the orchid.

To carry pollen the Catasetum fimbriatum attracts by very perfumed chemical substances the male hymenopterans. This genus, native to Central and South America, has inflorescences with unisexual flowers and this is singular in Orchidaceae family. In fact, after the growth conditions, develop male or female flowers © Giuseppe Mazza

Similarly, Cephalanthera rubra (L.) Rich. that has the perigone formed by 6 pieces, imitates the flower of various species of Campanula and utilizes the pronubes of these species for its pollination without giving in return any reward.

Besides the visual trick, many orchids have developed the chemical trick. The flowers can produce attractive odours and even nectar in the spur of the labellum, on the margins of the sepals or on the septa of the ovary. Some orchids produce also the pheromones released by the females of the pollinating insects; with this strategy, the male gets close to the flower and, thinking of being mating, performs, instead, the pollination.

The species of the genus Drakaea have the labellum similar in shape and size to the females of wasps of the subfamily Thynninae (Vespoidea). It is the males who pollinate these orchids.

Proplebeia dominicana fossil, a small bee conserved in amber, lived 15-20 million years ago, has on the back the pollinia of a fossil orchid © Santiago Ramirez

The females of these wasps do not have wings and so are unable to fly. When they get out from the ground, they climb a blade of grass, and rub their legs to free the pheromone that attracts the males. The male perceives the pheromone, flies into the wind till when it encounters the female, then holds it, raises it and mates while flying up to bring it into the shrubs with the flowers rich in nectar. After having fed it, it leaves it on the soil in order it can lay the eggs inside the larvae of coleopterans (Scarabaeoidea) before dying.

The species of Drakaea (i.e. Drakaea elastica Lindl.) have transformed their labellum in way that the male of the wasp is mistaken by its shape that resembles to the female and so, when the male tries to fly away with the labellum, making move backwards the stem supporting it, the pollinia stick without being able to detach the labellum. The male gets tired and flies away. It is however necessary that another male comes to visit the flower and follows the same procedure. Only in this way the pollen deposits on the stigma and the plant is pollinated.

The Meliorchis caribea probably was one of the first orchids to invent pollinia. Still now in some species, like Vanilla planifolia here on the left, the pollinic grains are freed singularly, but as they have thousands of ovules to fertilize, almost all modern orchids prefer to carry them grouped in mass with two sacs, called pollinia, supported by a filamentous structure, the caudicle. The pollinia are stuck to the pronubes insects with the viscidium, a viscous gland, here on the top of the right photo © Giuseppe Mazza

Also in the genus Ophrys, the labellum has a shape and smell imitating the body of the receptive females. The labellum reproduces the abdomen of the insect female with the typical hairiness and, in the centre, with the glossy and glabrous macula. This structure has an attraction of sexual type, as the insect male, seduced by visual stimuli, but also tactile and olfactory, believes to be mating with the female, but actually it does not do anything else than pollinate the flower.

In the cold regions, if there are no pollinators, some orchids (Neottia nidus-avis (L.) Rich., Epipactis muelleri Godfery, etc.) do the self-pollination. The caudicles dry up and the pollinodes fall directly in the stigma. In Holcoglossum amesianum (Rchb.f.) Christenson the anther rotates to insert in the cavity of the stigma performing the self-fertilization. The plant, not producing perfume or nectar, saves energy that can be destined to something else but meets the problems linked to the poor genetic variability.

Aerides odorata and Coryanthes verrucolineata. Very often the insects are attracted by the nice irresistible scents that often have to do with their sexuality. Some are fed in exchange for the pollinic transport, others are imprisoned or are even tortured. The unfortunate males of Englossa genus land hoping to be given a good meal and instead they fall in well filled with a liquid that hinders them to fly. Plodding follow an obligatory path that sticks them firmly, when exiting, the two pollen sacs © Giuseppe Mazza

Also Paphiopedilum parishii reproduces by self-fertilization by means of the deliquescence of the anther that gets in touch directly with the stigma without the necessity of pollinator. In some orchids, like Limodorum abortivum (L.) Sw., the self-fertilization may occur even without the opening of the flowers (cleistogamy).

In the Cypripedioideae the labellum has the shape of a sac, similar to a slipper, that has the function of trapping the visiting insects who, obliged to pass through the only one exit, go beyond the staminoid fertilizing the flower.

Many neotropical orchids of continental tropical America, like Stanhopea (S. florida Rchb.f., S. candida Barb. Rodr., S. costaricensis Rchb.f., S. tricornis Lindl.), Catasetum (C. macrocarpum Rich. ex Kunth,) and Notylia (N. pentachne Rchb.f.) are pollinated by male hymenopterans (Eufriesea spp., Euglossa spp. and Eulaema spp.) attracted by very perfumed chemical substances emitted by these plants, that the males collect for utilizing them, maybe as precursors of own pheromone, in the territorial exhibition and in the courting done to attract the females and mate.

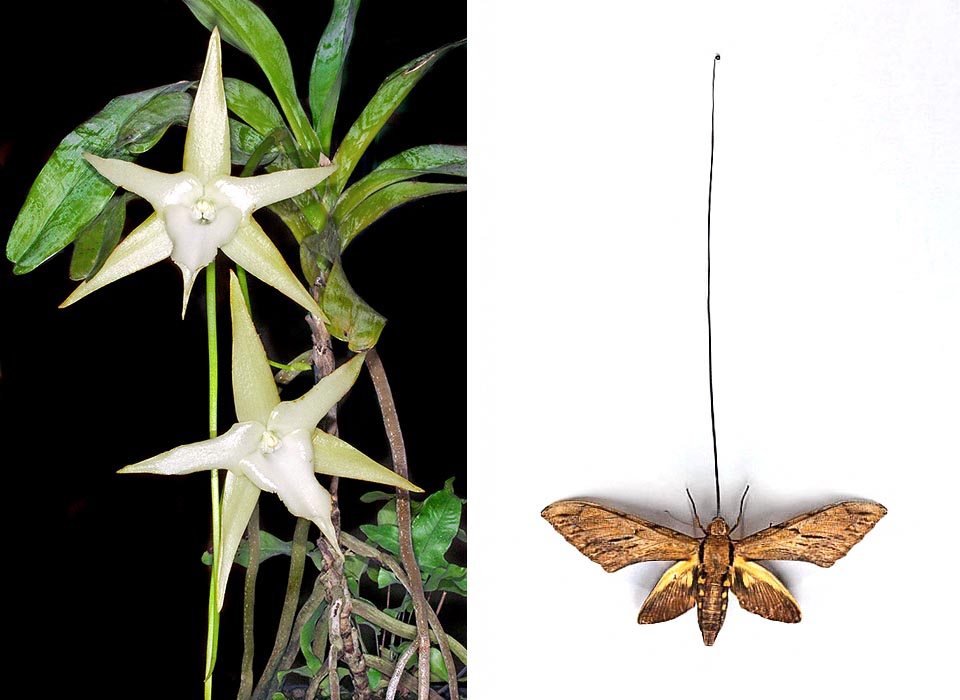

Angraecum sesquipedale instead is a king orchid, but only for one special client. It is currently known as Darwin’s orchid because in 1862 he wrote: ‘…. in many flowers sent to me by Mr. Bateman, I have found eleven and a half inches long nectaries and only the lower part up to one and a half inch long full of nectar. We can wonder what for can serve a nectary of such disproportionate length …. we are amazed … but in Madagascar must exist moths whose proboscis can be up to ten or eleven inches long!’. Darwin hypothesis was confirmed in 1903 by the entomologists Rothschild and Jordan who found the lepidopter pollinating this orchid, described as Xanthopan morganii praedicta © John Varigos (left) and © nickgarbutt.com (right)

Another strategy to attract the pollinators is done by Epipactis veratrifolia Boiss. & Hohen., species native to Middle East, Africa and Asia, that is pollinated by various species of Hoverflies. These dipterans usually nourish of aphids who, when in danger, release chemical substances for warning their similars. The Hoverflies recognize these substances and proceed towards the source of the odour. The orchid exploits this way of stocking of food emitting the same odour of the chemical substances released by the aphids. In this way it attracts the females first, that gather around the flowers thinking of having found a good meal, and immediately after, the males that take advantage for mating.

Dendrobium sinense Tang & F.T.Wang, species endemic to the Chinese island of Hainan, is pollinated by Vespa bicolor, a hymenopteran similar to a hornet as having no black stripes. The plant attracts the wasp producing an odorous substance similar to that released by the Asian honey bee (Apis cerana) when it is in situations of danger. Being Vespa bicolor carnivorous and having to nourish its own larvae with the Asian honey bee, is attracted by the possibility of meeting its prey but, deceived, finds only the flower of the orchid it pollinates.

Dendrobium nindii and Orchis purpuria fruits. Orchids fruits are dehiscent capsules with 3 or 6 longitudinal fissures keeping closed in both extremities © Giuseppe Mazza

The genus Catasetum native to Central and South America has inflorescences with unisexual flowers and this is a singularity in the family Orchidaceae. In fact, depending on the conditions of growth, develop male or female flowers. Catasetum maculatum Kunth has such different flowers that once it was thought that they were two separate species. The difference of the flowers interests the dimension as well as the colours. The female flowers are yellowish green, the male ones are multicoloured. Some days after opening, the male flowers emit strong odours to attract the pollinators.

Rhizanthella slateri M.A.Clem. & P.J.Cribb grows in Australia completely underground and is a rare example of saprophyte orchid, having no chlorophyll. Only the flowers, when ripe, rise from the litter, in order to allow the pollination, which is done by ants, flies and other insects.

The fruits of the orchids develop from the fecundated ovary and are typically a capsule dehiscent by means of three of six longitudinal fissures, remaining close on both extremities.

Cymbidium finlaysonianum open fruits. The orchids seeds usually are microscopic and very numerous. When they are ripe, they go away like spore particles. They have no secondary endosperm feeding embryo and for germinating they need to get in symbiosis with the fungi that are offering them the necessary nutrients © Giuseppe Mazza

The seeds are usually microscopic and are very numerous. When ripe they go away like spore particles. They do not have the secondary endosperm that gives the food to the embryo and consequently they must enter in symbiosis with mycorrhizal fungi belonging to various orders of basidiomycetes that furnish them the nutrients necessary for germination.

All species of orchids, in order to have the seeds germinating, need the input of fungi (mycoheterotrophy) belonging to the basidiomycetes (i.e. Rhizoctonia, Tulasnella, Ceratobasidium, etc.) thanks to which they obtain the carbon instead of getting it from the photosynthesis.

Besides sexual reproduction, the Orchidaceae may reproduce also asexually. Some species of the genera Phalaenopsis, Dendrobium and Vanda, reproduce by offshoots, equipped with roots, emitted by the nodes of the stem. These buds are the so-called keiki, Hawaiian word meaning “child”.

Some species of the genus Gymnadenia (i. e. Gymnadenia rubra Wettst.,) can reproduce without resorting to a gamic act but by apomixis, that is that vital seeds form without the necessity of fertilization.

The parthenogenesis is an example of apomixis as the female gamete develops (without fertilization) originating a new individual who will have exclusively maternal characters.

In 2014 in the magazine Nature Genetics has appeared the first article concerning the sequencing complete of the genome of the orchid Phalaenopsis equestris (Schauer) Rchb.f., epiphyte orchid, native to Philippines and Taiwan, very utilized by the horticulturists because of the beauty of the flowers having colours going from the white to the intense pink. The complete sequencing has been reached thanks to the project “Orchid Genome Project”, coordinated by the researchers Lai-Qiang Huang and Zhong Jian Lic of the Tsinghua University of Beijing. It is the first plant with metabolism CAM (Crassulacean Acid Metabolism) of which has been sequenced the genome. It has been noted that the assembled genome contains 29.431 genes codifying proteins. Moreover, the researchers have located the so-called genes MADS-box, C / D-class, B-class AP3 and AGL6-class, that play an important rôle in the development of the flower. Reconstructing the history and genetic evolution of this plant, it has been noted that in the genome are present also old events of duplication of vast sequences of the DNA that might be involved in the development of the photosynthesis CAM as a mechanism adaptive to the environment. The duplication is the mechanism through which parts of the genome are copied more than once and join the genome itself, elongating it. The duplicated genes may accumulate mutations without major problems as the original gene is always present and active, therefore the possible mutation, even if dangerous, in the copy does not create problems to the organism. It is possible that in the orchids these duplications have allowed the creation of more genes able to perform synergistic or antagonistic actions influencing the final structure of the flower. The quantity and quality of the genes expressed, therefore, determine exactly the differences.

The complete sequencing of the Phalaenopsis equestris genome has shown the presence in orchids of duplicate genes to adapt quickly the flower characteristics to a possible change of the pronubes and also these have often adapted to the flower structure to ensure the reward. Here, we talk of coevolution © Giuseppe Mazza

The duplicated genes represent an investment and a remarkable cost for the organisms, and usually are eliminated. If, instead, they are conserved and maintained active, that means that, somehow, they are useful offering, rather, advantages and for this reason the selection keeps them. As the orchids, for reproducing, need that the pollination is made by pronubes of species of different groups, (hymenopterans, coleopterans, lepidopters, hummingbirds), it is the structure of the flower that interacts with the pronubes. If changes occur for the mutations of its morphology, it can be determined greater or lesser attraction towards the pronubes. The presence of the numerous duplicate genes, with the time has permitted to make the most of this mechanism, generating, from time to time, structures suitable to sustain increasingly targetted strategies.

It is also true that between the orchids and the pronubes has happened a process of joint evolution (coevolution) that has interacted so strongly to become a strong selective factor for both species influencing each other. In fact, in the orchids having nectar, on one side the plant tries to increasingly adapt to the pronube, on the other, this latter modifies in a way to ensure its reward.

The leaves can be thin and deciduous as in Dendrobium pseudolamellatum, left, or last several years, coriaceous or waxy, as in Dendrobium ramificans © Giuseppe Mazza

However, if inside a species of a so specialized orchid, due to the interaction with a particular pronube, takes place a mutation on the labellum, and it changes in way to be exchanged for the female of the pollinator, the plant will not have to produce nectar and consequently will get an energy saving it will be able to invest, as an example, in producing seeds. And now, it is possible that, despite the orchid has modified its flower rendering it similar to the female of its pronube and even able to resist the long waits (many orchids have long lasting flowers), this has not been sufficient and so the plant has been obliged to reinforce the call mechanism.

This is what happens in Ophrys sphegodes Mill., besides having the labellum similar to the female of Andrena nigroaenea (Andrenidae, Hymenoptera) emits all pheromones identical to those released by the females of this insect, in this way attracting many males, has guaranteed its own pollination.

In 1964 was discovered, trapped in an amber of the Dominican Republic, a small bee, without sting and described as Proplebeia dominicana Wille et Chandler dating back to the Early and Middle Miocene (about 15-20 million years ago).

And there are orchids nice for the leaves, like Lepanthes calodyction or Trichosalpinux rotundatache, protecting, like jewels, tiny flowers © Giuseppe Mazza

Stuck to the wing of this fossil bee, the paleontologists have seen and then described in 2007, a mass of pollen on the back of the insect, belonging to a species of unknown and extinct that the discoverers did call Meliorchis caribea close to the modern genera Ligeophila, Kreodanthus and Microchilus of the subtribe Goodyerinae.

This has been the first fossil orchid discovered and that has allowed to evaluate the origin of the Orchidaceae. The genic sequencing has shown that the common ancestor of the family lived in the Late Cretaceous (76-84 million of years ago) and, after the massive extinctions of the Cretaceous – Paleocene (about 65-95 million of years ago), elements of this family discovering new free territories had a radiation leading them to colonize all continents.

The sequencing has also confirmed that the subfamily Vanilloideae is a basal branch. Moreover, as the subfamily has diffused all over the world, it is quite possible that the origin of the Orchidaceae dates back to about 80-100 million years ago when the continents were on the way of separating.

Needless to say that man took advantage of the imaginative beauty, always present in the orchids world, to create countless hybrids, like Papilionanthe ‘Miss Joaquim’, the beautiful and famous Singapore national flower, right, born from crossing Papilionanthe kookeriana, picture left, and Papilionanthe teres, in the center © Giuseppe Mazza

This is corroborated by the fact that the orchids are cosmopolitan, present in almost all habitats excluding the glaciers and the deserts. The richest diversity of genera and of species of orchids is located in the tropics, but even beyond the Arctic Polar Circle, to southern Patagonia, and two species, Nematoceras are present in Macquarie Island, not far from Antarctica.

The presently known genera have the following distribution: Oceania 50 to 70 genera; North America 20 to 26 genera; tropical America 212 to 250 genera; tropical Asia 260 to 300 genera; tropical Africa 230 to 270 genera; Europe and temperate Asia 40 to 60 genera.

The systematics of the Orchidaceae is traditionally based on the structure of gynoecium and of the androecium that are united together (gynostemium). Yore, the number of anthers has led to the division of the family in three groups, often recognized as subfamilies, or tribes. The Polyandrae whose flowers are almost regular with 3(5) stamens and 3 stigmas all pollinable; the Diandrae with zygomorphic flowers with 2 stamens and 3 pollinable stigmas and the Monandrae with zygomorphic flowers, one only stamen and 2 pollinable stigmas, the third is transformed in rostellum ovehanging the anther and on which is fixed the (retinaculum) or viscidium, the sticky disk of the pollinodes.

The Cattleya hybrids due to their showy colours and the big size, are now present in the shops of all florists with hundreds of varieties © Giuseppe Mazza

More recently, the studies of morphological taxonomy have recognized five subfamilies but with the advent of the DNA research not all have been supported by the molecular phylogenetics. The new studies continue more and more to clarify the relationships among the membres subjecting them to constant change. The system APG III (2009) and APG IV (2016) (Angiosperm Phylogeny Group) inserts the family Orchidaceae in the order of Asparagales. The systematics here adopted follows M. W. Chase et al. (2015). In brackets is shown the number of the species present in the single genera.

Nowadays, inside the family Orchidaceae are recognized five subfamilies all monophyletic: Apostasioideae, Vanilloideae, Cypripedioideae, Orchidoideae and Epidendroideae. The subfamily Epidendroideae includes about 576 genera and 21,000 species and represents the greatest part of the Orchidaceae.

The taxonomy of the Orchidaceae is not a simple thing and with its man-like look this Orchis purpurea seems to smile to the botanists worrying to group them in subfamilies, tribes, subtribes, genera and species © G. Mazza

The subfamily Apostasioideae forms the basal evolutive branch of the Orchidaceae.

Therefore, it is the oldest one. It is characterized by the presence of three fertile anthers or two fertile anthers and one filamentous staminode.

It includes the genera Apostasia with 6 species and Neuwiedia with 8 species. They are terricolous orchids diffused in tropical Asia, in the Indian-Malay archipelago and in northern Australia.

The subfamily Vanilloideae includes species whose phylogenetic position has long been controversial.

It is characterized by the presence of only one fertile stamen. It consists of 14 genera and about 1470 species typical to the tropical regions of Asia, Australia and the Americas.

The species of the tribe Pogonieae have the border of the labellum fringed (laciniate). The colour of their petals and sepals is pink or rarely white or bluish. Their sepals have an oblong, elliptic or strictly lanceolate shape.

The species of the tribe Vanilleae are climbers with long flexible stems, of reddish colour, with monopodial growth, with aerial roots that form in the nodes and anchoring on the host plant.

The flowers are gathered in racemose inflorescences of white to green colour. The labellum is tubular and surrounds the gynostemium on whose apex stands the anther (i.e. Vanilla chamissonis Klotzsch). The blooming is very short, as is usually lasting one day.

The tribe Pogonieae has 5 genera: Cleistes (64), Cleistesiopsis (2), Duckeella (3), Isotria (2), Pogonia (5) totalling 76 species.

The tribe Vanilleae has 9 genera: Clematepistephium (1), Cyrtosia (5), Epistephium (21), Eriaxis (1), Erythrorchis (2), Galeola (6), Lecanorchis (20), Pseudovanilla (8), Vanilla (105) , totalling 169 species.

The subfamily Cypripedioideae has a world-wide distribution and regroups species, mainly terricolous, with two fertile anthers and one shield-shaped staminode and one sac-like lip. It includes the genera: Cypripedium (51), Mexipedium (1), Paphiopedilum (86), Phragmipedium (26), Selenipedium (5) for a total of 169 species. The species Cypripedium calceolus L. is present in Italy.

The subfamily Orchidoideae includes perennial herbaceous plants up to 2 m tall.

The subfamily Cypripedioideae is cosmopolitan. Includes mainly terricolous species, with two fertile anthers and a shield-shaped staminode © Giuseppe Mazza

They have an underground rhizome that regenerates annually with new roots and adventitious stems. They have zygomorphous and pentacyclic flowers. The perigone is formed by two verticils of petals, also the stamens are on two verticils, of which one is atrophied. The style stands on only one verticil. The species of this family have an almost cosmopolitan distribution, excluding the polar and desert zones and live in quite different habitats. The European species prefer the shady zones, cool and humid of the underwoods or open of alpine type (i.e. Chamorchis alpina (L.) Rich.), whilst the tropical ones live in humid and warm environments of the equatorial forests. This subfamily is quite numerous and together with the subfamily Epidendroideae represents the most recent evolutive level of the Orchidaceae. With the more primitive subfamily of the Vanilloideae it belongs to the clade Monandrae due to the presence of only one fertile stamen.

The taxonomy of the Orchidoideae has undergone various reshuffles during the years.

Present in Ecuador and Peru, Porphyrostachys pilifera belongs to the subfamily Orchidoidae © Giuseppe Mazza

With the new cladistic and molecular analysis have been improved the phylogenetic affinities even if not in a definitive way. It includes the tribes Codonorchideae, Cranichideae, Diurideae, Orchideae and 21 subtribes.

The tribe Codonorchideae has only the genus Codonorchis with two species, C. canisioi Mansf. of Brazil (State of Rio Grande do Sul) and C. lessonii (d’Urv.) Lindl. of Argentina, Chile, Falkland Islands. They are small terricolous orchids, with rapid growth, having 2-4 basal leaves and with the floral axis of pale green colour, erect (up to 40 cm), carrying only one, very delicate, white flower, almost regular, with three sepals and three petals with small violet dots. The two species distinguish because of some vegetative and floral characteristics. C. canisioi Mansf. is a species under risk of extinction due to the fires and the pastureland.

The tribe Cranichideae includes terricolous and epiphyte herbaceous perennial species a few decimetres up to 2 m tall. The tropical species are epiphyte, with temporary roots often covered by the velamen that allows the plant to absorb the air humidity. The leaves, the basal ones arranged in rosette, entire, ovate-oblong with pointed apex, the cauline ones of lanceolate-linear shape, are spiralled, green, often reduced and wrapping the stem (amplexicaul). In some species, the leaves do not have chlorophyll and appear of pale brown colour or are reduced to scales. The flowers grouped in spikes or in raceme inflorescences. The disposition of the flowers can be spiralled or unilateral. Normally, the flowers are resupinate, that is, rotated by 180° with labellum down, but in other species, like in Prescottia stachyodes (Sw.) Lindl. and Catasetum maculatum Kunth, there is no resupination.

The tribe Cranichideae divides in the following subtribes:

– Subtribe Chloraeinae with the genera: Bipinnula (11), Chloraea (52), Gavilea (15);

– Subtribe Cranichidinae with the genera: Aa (25), Altensteinia (7), Baskervilla (10), Cranichis (53), Fuertesiella (1), Galeoglossum (3), Gomphichis (24), Myrosmodes (12), Ponthieva (66), Porphyrostachys (2), Prescottia (26), Pseudocentrum (7), Pterichis (20), Solenocentrum (4), Stenoptera (7);

– Subtribe Galeottiellinae with the only genus Galeottiella (6);

– Subtribe Goodyerinae with the genera Aenhenrya (1), Anoectochilus (43), Aspidogyne (60), Chamaegastrodia (3), Cheirostylis (53), Cystorchis (21), Danhatchia (1), Dossinia (1), Erythrodes (26), Eurycentrum (7), Gonatostylis (2), Goodyera (98), Halleorchis (1), Herpysma (1), Hetaeria (29), Hylophila (7), Kreodanthus (14), Kuhlhasseltia (9), Lepidogyne (1), Ligeophila (12), Ludisia (1), Macodes (11), Microchilus (137), Myrmechis (17), Odontochilus (25), Orchipedum (3), Pachyplectron (3), Papuaea (1), Platylepis (17), Rhamphorhynchus (1), Rhomboda (22), Schuitemania (1), Stephanothelys (5),Vrydagzynea (43), Zeuxine (74);

Goodyera repens, present in the conifer mountain woods of Central-North Italy, belongs to the Gooderinae © Giuseppe Mazza

– Subtribe Manniellinae with the only genus Manniella (2);

– Subtribe Pterostylidinae with the genera Pterostylis (211), Achlydosa (1);

– Subtribe Discyphinae with the only genus Discyphus (1);

– Subtribe Spiranthinae with the genera: Aracamunia (1), Aulosepalum (7), Beloglottis (7), Brachystele (21), Buchtienia (3), Coccineorchis (7), Cotylolabium (1), Cybebus (1), Cyclopogon (83), Degranvillea (1), Deiregyne (18), Dichromanthus (4), Eltroplectris (13), Eurystyles (20), Funkiella (27), Hapalorchis (10), Helonoma (4), Kionophyton (4), Lankesterella (11), Lyroglossa (2), Mesadenella (7), Mesadenus (7), Nothostele (2), Odontorrhynchus (6), Pelexia (77), Physogyne (3), Pseudogoodyera (1), Pteroglossa (11), Quechua (1), Sacoila (7), Sarcoglottis (48), Sauroglossum (11), Schiedeella (24), Skeptrostachys (13), Sotoa (1), Spiranthes (34), Stalkya (1), Stenorrhynchos (5), Svenkoeltzia (3), Thelyschista (1), Veyretia (11).

The tribe Diurideae regroups terricolous species of the southern hemisphere, distributed in Australia, New Zealand and New Caledonia, with peripheral representatives in Malaysia, parts of Oceania, Japan, East Asia and South America. The floral structure has had great importance for the systematics of the orchids and, in paticular, the shape of the column, and the position of the pollinia and of the related structures in respect to the rostellum and to the stigma. Also other parts of the plant have been studied, as the tubers and the shape of the leaves, but not all authors have been in agreement.

Even molecular studies have recognized the presence of tubers in the basal lineages of the Orchidoideae hypothesizing that their presence in the Diurideae and Orchideae can be relatively primitive (plesiomorphous) or convergent.

As a consequence, the Diuridaee remain difficult to characterize morphologically and are also problematic their possible affinities inside the family. New and recent studies hypothesize that the common ancestor of the tribe Diurideae has been pollinated by bees attracted deceptively to visit the flowers, having not nectar, because of their resemblance to the flowers furnishing nectar or pollen. Therefore, it is possible that the species and their descendants who have attracted the pollinators in offering nectar, with the false promise of sex or that have completely given up to the crossed pollination (autogamous species), have evolved several times from such predecessors.

The tribe Diurideae includes 9 subtribes.

– Subtribe Acianthinae. with the genera Acianthus (20), Corybas (132), Cyrtostylis (5), Stigmatodactylus (10), Townsonia (2);

– Subtribe Caladeniinae with genera Adenochilus (2), Aporostylis (1), Caladenia (267), Cyanicula (10), Elythranthera (2), Ericksonella (1), Eriochilus (2), Leptoceras (1), Pheladenia (1), Praecoxanthus (1);

Dactylorhiza sambucina, frequent in two colours in the alpine pastures, belongs to the tribe of Orchideae and to the subtribe of the Orchidinae © Giuseppe Mazza

– Subtribe Cryptostylidinae with the genera Coilochilus (1), Cryptostylis (23);

– Subtribe Diuridinae with the genera Diuris (71), Orthoceras (2);

– Subtribe Drakaeinae with the genera Arthrochilus (15), Caleana (1), Chiloglottis (23), Drakaea (10), Paracaleana (13), Spiculaea (1);

– Subtribe Megastylidinae with genera Burnettia (1), Leporella (1), Lyperanthus (2), Megastylis (7), Pyrorchis (2), Rimacola (1),Waireia (1);

– Subtribe Prasophyllinae with the genera Genoplesium (47), Microtis (19), Prasophyllum (131);

Dactylorhiza sambucina close-up. Anacamptis pyramidalis and Orchis militaris are also membres of the subtribe of the Orchidinae © Giuseppe Mazza

– Subtribe Rhizanthellinae with the only one genus, the Rhizanthella (3);

– Subtribe Thelymitrinae with genera Calochilus (27), Epiblema (1), Thelymitra (110).

The tribe Orchideae is the largest in the subfamily Orchidoideaewith more than 2,100 species. During the last twenty years have been clarified many affinities of its membres but are still necessary other studies to solve the relationships between some of its subtribes.

Moreover, it has been ascertained that the subtribe Orchidinae has diversified in the Mediterranean Basin during the last 15 million of years. Whilst the systems of pollination have changed in numerous instances in the last 23 million of years. The studies indicate that the ancestral species of this subtribe were plants pollinated by hymenopterans misled by the food and this has influenced the evolutive history of the subtribe Orchidinae in the Mediterranean. Furthermore, it has been ascertained that the beginning of the sexual deception could be linked to the increase of the dimensions of the size of the labellum and that the diversification of the species of this subtribe has developped parallelly to the diversification of the bees and of the wasps that started in the Miocene about 23 million of years ago.

In Gymnadenia conopsea, subtribe Orchidinae, frequent in Eurasia, we find, though reduced in small rural orchid, the long nectariferous spurs of Angraellum sequipedale, and analogously pollinated by moths with their suitable proboscis © Giuseppe Mazza

The tribe includes more than 2,000 species and is divided in 4 subtribes.

– Subtribe Brownleeinae with two genera Brownleea (8) and Disperis (78);

– Subtribe Coryciinae with the genera Ceratandra (6), Corycium (15), Evotella (1), Pterygodium (19);

– Subtribe Disinae with the genera Disa (182), Huttonaea (5) and Pachites (2);

– Subtribe Orchidinae with the genera Aceratorchis (1), Anacamptis (11), Androcorys (10), Bartholina (2), Benthamia (29), Bhutanthera (5), Bonatea (13), Brachycorythis (36), Centrostigma (3), Chamorchis (1), Cynorkis (156), Dactylorhiza (40), Diplomeris (3), Dracomonticola (1), Galearis (10), Gennaria (1), Gymnadenia (including the genus Nigritella), (23), Habenaria (this genus is not monophyletic) (835), Hemipilia (includes species previously assigned to the genera Amitostigma e Ponerorchis) (13), Hsenhsua (1), Herminium (19), Himantoglossum (11), Holothrix (45), Megalorchis (1), Neobolusia (3), Neotinea (4), Oligophyton (1), Ophrys (34), Orchis (21), Pecteilis (8), Peristylus (103), Physoceras (12), Platanthera (136), Platycoryne (19), Ponerorchis (55), Porolabium (1), Pseudorchis (1), Roeperocharis (5), Satyrium (86), Schizochilus (11), Serapias (13), Silvorchis (3), Sirindhornia (3), Stenoglottis (7), Steveniella (1), Thulinia (1), Traunsteinera (2), Tsaiorchis (1), Tylostigma (8), Veyretella (2).

Subfamily Epidendroideae

The subfamily Epidendroideae includes almost the 80% of the species of orchids, with its 576 genera and about 21,000 species. The species, present in the tropical and subtropical areas, are epiphyte, at times with pseudobulbs, those in the temperate zones are terricolous. For their growth, some species require mycorrhizical fungi. Mycoheterotrophic species distinguish, like mycoheterotrophic and Cephalanthera austiniae (A.Gray) Heller, Cephalanthera exigua Seidenf and Neottia nidus-avis (L.) Rich. without chlorophyll with fleshy roots and without radical hair, and mixotrophic, species, such as Limodorum abortivum (L.) Sw. and Platanthera minor (Miq.) Rchb.f. more or less green with long roots, more or less hairy that have mycorrizhical relations with species of the genera Russula and Ceratobasidium (Basidiomycota) In particular, P. minor, subjected to the analysis of stable isotopes, has shown that the input to the mixotrophic feeding of the fungal carbon varies from 50% to 65%. It is possible that the mycoheterotrophy by the mixotrophy may have evolved independently from autotrophic ancestor.

The species of the subfamily are characterized by one only fertile anther (clade Monandrae, term with which in the past was defined the subfamily.

They are perennial grasses, terricolous, epiphyte or lithophyte or, rarely, climbers, sympodial or monopodial, with short or long rhizomes. At times with absent leaves (achlorophyllous) or reduced in scales. Roots with velamen, smooth to warty, round or flat. The stems are usually leafy, with one or more internodes, often swollen at the base (pseudobulbs). The leaves, if present, are entire, usually alternate, often fleshy or coriaceous. The inflorescences are erect or pendulous, racemose or panicle-like, with many flowers or only one. The flowers can be small or big, mainly resupinate, glabrous to hairy. The sepals are usually free but at times united at the base and adnate at the foot of the column. The petals are often big, similar or not so much to the sepals; the lip is entire, variously lobed, with or without basal spur or nectary. The column can be short or long, at times merged with convex and ascending anther on the borders like a hat. The shape of the anther is given by the extension of the column or, as in Vanda by the anterior flexion of the anthers. The pollinia are floury or waxy on the viscidium, if present. The stigma, viscous with rostellum, usually transversal, has one to three lobes, bent with a beak over the apex of the gynostemium. The fruit is a capsule with 3 or 6 fissures that free many seeds, powdery, with no endosperm, winged at times. Many species of the subfamily are very flashy and are often utilized in the hybridization.

The small Epipactis atrorubens has very vast distribution from Europe to Japan. Belongs to the Neottieae, inserted in the endless Epidendroideae subfamily boasting 576 genera and about 21.000 species, almost the 80% of the extant orchids © Giuseppe Mazza

The systematics of the Epidendroideae is rather complex and is subject to continuous reshuffles.

Presently, the subfamily, for systematic convenience, is divided in two major groupings: Epidendroideae superior and Epidendroideae inferior. The Epidendroideae superior have evolved after the Epidendroideae inferior and are partly monophyletic and partly polyphiletic, like the tribes Arethuseae and Epidendreae.

The Epidendroideae inferior include the tribes: Neottieae, Sobralieae, Tropidieae, Triphoreae, Xerorchideae, Wullschlaegelieae, Gastrodieae, Nervilieae, Thaieae some of which divided in subtribes.

The Epidendroideae superior regroup the tribes: Arethuseae, Malaxideae, Cymbidieae, Epidendreae, Collabieae, Podochileae, Vandeae, these also divided in subtribes.

Tribe Neottieae

The tribe Neottieae has a cosmopolitan distribution, whose species are located mainly in the temperate and subtropical zones of the northern hemisphere. It counts about 180 species, being many of them totally or partially unable to produce the photosynthesis. The habitat is quite various: in temperate zones in the chestnuts woods and in the beech ones (i.e. Cephalanthera) or, in cool and shady zones of the woods rich in humus (i.e. Neottia). The species of the genus Epipactis, with paleoarctic distribution, are present in the woods and in the open humid areas.

The tribe Neottieae includes the genera Aphyllorchis (22), Cephalanthera (19), Epipactis (49), Limodorum (3), Neottia (64), Palmorchis (21).

Tribe Sobralieae

It is a small tribe with 4 genera and about 269 species typical to the neotropical flora (South America). Most of the species of these four genera form long stems like canes, but the species differ in the dimension of the flower and the structure of the inflorescence. The molecular data support the monophyly of Elleanthus, Epilyna and Sertifera but not of Sobralia, that decidedly is a polyphyletic genus characterized by relatively big flowers. With few exceptions, the species of Sobralia are all pollinated by the bees and mainly do not offer any reward. The species of Elleanthus and Sertifera, that have small flowers, are mostly pollinated by hummingbirds but do offer rewards.

The tribe Sertifera, includes the genera Elleanthus (111), Epilyna (2), Sertifera (7), Sobralia (149).

Tribe Tropidieae

The tribe has a pantropical distribution: the genus Corymborkis (6) is mainly diffused in America with two species in Africa (Corymborkis corymbis Thouars, C. minima P.J. Cribb) and one in Asia (C. veratrifolia). The genus Tropidia (31) has species present mainly in South-East Asia, only one is located in North and Central America.

Dendrobium glumaceum is a Borneo and Philippine epiphyte or lithophyte with odd 20-50 cm long inflorescences © Giuseppe Mazza

Tribe Triphoreae

The species of this tribe are terricolous, rhizomatose with fleshy roots. They have thin stem, with several small leaves arranged alternately. The inflorescence is in cluster or corymb, carried at the axil of the higher leaves and formed by few small flowers. At times the inflorescence is reduced to only one flower. The flowers are ephemeral, inconspicuous. The gynostemium is long, erect or slightly arcuate. Are present four white oblong and powdery pollinia, without caudicle, the staminodes are totally incorporated in the part of the column and the stigma is ventral, trilobed or more or less concave at the base. Triphora trianthophora (Sw.) Rydberg is the most known species of this tribe.

It divides in two subtribes. The subtribe Diceratostelinae with the genus Diceratostele and the only species D. gabonensis Summerh., and the subtribe Triphorinae with the genera Monophyllorchis (1), Pogoniopsis (2), Psilochilus (7), Triphora (18).

Dendrochilum latifolium var. macranthum looks like the previous species. Also here the spikes are formed by tiny flowers. © Giuseppe Mazza

Tribe Xerorchideae

This tribe includes terricolous orchids of South America grouped in only two species (Xerorchis amazonica Schltr. and X. trichorhiza (Kraenzl.) Garay). They present 8 pollinia and thin bamboo-like stems and persistent leaves.

Tribe Wullschlaegelieae

It includes the only genus Wullschlaegelia with two species having a neotropical distribution going from southern Mexico to large part of southern America. They are terricolous orchids, having no chlorophyll, that get the nutrients from fungi of the soil (mycoheterotrophic).

Tribe Gastrodieae

Arundina graminifolia and Coelogyne fimbriata. These two genera, with Dendrochilum, are inserted in Arethuseae that includes epiphyte, lithophyte or terricolous species © Giuseppe Mazza

This tribe includes terricolous saprophytic (mycoheterotrophic) herbaceous species, without leaves, with tuberose rhizome, fusiform. Auxopus is diffused in tropical Africa and in Madagascar with plants having long, fleshy and thickened underground rhizomes. The flowers are not too evident inflorescences of brown colour.

The sepals and the petals have grown at the base. The labellum is white, wider than the other petals, smooth or slightly bilobed edges. Didymoplexiella is a genus with 8 species native to North-West Asia, some extending northwards in Japan and in southern China. Didymoplexis, includes species known as ‘crystal orchids’ due to the short-lasting white flowers. The rhizome is fleshy and the floral axis is erect with one or few resupinate flowers. The sepals and petals are united at the base, forming a bell-shaped tube. The labellum is quite ample and has a callous yellow band along its median line. The species of this genus are native to Africa, Madagascar, South-East Asia, Australia and various islands of Pacific.

Easy to grow, Brazilian Brassavola flagellaris is much required by collectors due to the perfumed long-lasting inflorescences © Giuseppe Mazza

Gastrodia is a genus diffused in Asia, Australia, New Zealand, tropical Africa and in various island of the Pacific and Indian oceans. It counts terricolous, mycoheterotrophic, leafless orchids, with tuberous and cylindrical rhizome. The inflorescence is erect, terminal, of yellow to brown colour. The sepals and the tepals are merged to form a tubular structure open at the apex; the labellum presents a gynostemium, with two pollinia having no caudicle. Also Uleiorchis is a mycoheterotrophic genus with two species native to Central and South America.

The tribe Gastrodieae includes the genera Auxopus (4), Didymoplexiella (8), Didymoplexis (17), Gastrodia (60), Uleiorchis (2).

Tribe Nervilieae

The species of this tribe are distributed in the tropical, subtropical and warm temperate regions of Eurasia, Africa, Australia and the islands of the south-western Pacific.

Sobralia xantholeuca. This genus, with more than 150 species, is the largest of Sobralieae tribe © Giuseppe Mazza

They are terricolous herbaceous plants, not too tall, with aerial rhizome and stems. Some species are aphyllous. From the rhizome can depart secondary roots of sympodial type ore same are absent. The aerial part of the stem is erect and if there is no chlorophyll (aphyllous stems) is of brown colour.

The leaves are absent in the subtribe Epipogiinae and are reduced to brownish membranous scales.

This subtribe has, therefore, saprophytic species. Instead, they are present in the subtribe Nerviliinae and are almost always basal or ovate or heart-shaped; the cauline ones are very reduced and amplexicaul.

The foliar lamina appears with very evident and clear veins; hairy on the upper side and violaceous in the lower one.

The inflorescence is a spike of racemose type with few or many flowers located in the axil of scaly bracts. Depending on the genus of belonging, the flowers can be resupinate or not. The anther is sloping over the apex of the gynostemium and is provided of a beak.

The fruit is a capsule containing numerous tiny seeds that require fungal symbiosis to germinate. In addition to sexual reproduction, these orchids are able to reproduce vegetatively thanks to the rhizome which is capable of giving rise to new individuals through adventitious buds.

The tribe Nervilieae is divided in two subtribes.

– Subtribe Nerviliinae with the only genus Nervilia (67);

– Subtribe Epipogiinae with the generai Epipogium (3) and Stereosandra (1).

Tribe Thaieae

The only species of this tribe is Thaia saprophytica Seidenf. diffused in temperate and tropical Asia. It is a terrestrial orchid with green violaceous sepals, petals green too and bright green labellum with one white longitudinal line at the centre.

Tribe Arethuseae

This tribe includes herbaceous species, epiphyte or lithophyte or, more rarely, terricolous, with globose or long stems, having or not pseudobulbs, and with roots covered by the velamen. The leaves may be one or more, usually coriaceous and alternate. The flowers, solitary or united in inflorescence, have free petals (Coelogyne mayeriana Rchb.f.) or partially united on the base. The labellum, with or without spur, is entire or trilobed, at times shaped like a sac, often inserted at the base of the column. The stigmatic cavity contains 4 to 8 pollinia.

The tribe has species present in south-eastern Asia, Oceania, North America and Caribbean.

Glomera acutiflora is a small New Guinea epiphyte with solitary 1,5 cm flowers. The genus, with more than 130 species, is inserted in Arethuseae tribe © Giuseppe Mazza

This tribe has two subtribes.

– Subtribe Arethusinae with the genera Anthogonium (9), Arethusa (1), Arundina (2), Calopogon (5), Eleorchis (1).

– Subtribe Coelogyninae with the genera Aglossorrhyncha (13), Bletilla (5), Bracisepalum (2), Bulleyia (1),Chelonistele (13), Coelogyne (200), Dendrochilum (278), Dickasonia (1), Dilochia (8), Entomophobiade (1),Geesinkorchis (4), Glomera (131), Gynoglottis (1), Ischnogyne (1), Nabaluia (3), Neogyna (1), Otochilus (5), Panisea (11), Pholidota (39), Pleione (21), Thunia (5).

The tribe Malaxideae is a major cosmopolitan tribe formed by almost 2,000 species and is distributed all over the world, excluding the polar and the desert regions. It abounds in the tropical regions, particularly in Australia and in tropical Asia, in the tropical Americas and in Africa. The tribe has a big number of species either terricolous or epiphytic with quite different vegetative organs but the morphology of the flowers is similar. The terrestrial genus Crepidium has the leaves significantly plicate, whilst the epiphytic genera have them conduplicate except Oberonia and some species of Liparis.

Inflorescence of Oberonia cholichophylla and very enlarged detail of flowers. This species belongs to the tribe Malaxideae, boasting 2000 species © Giuseppe Mazza

Typically, the flowers are very small, with a terminal anther usually having 4 pollinia, only four species do have two of them. The flowers take form on a terminal inflorescence. Many species of Malaxideae are pollinated by the midges of fungi and few are pollinated by ants and ichneumon wasp (Hymenoptera). Interesting is the flowering of Bulbophyllum nocturnum J.J.Verm., de Vogel, Schuit. & A.Vogel, an epiphytic species discovered in 2011 in New Britain (Papua New Guinea), characterized by flowers opening only during the night and closing in the day.

The tribe Malaxideae is divided in two subtribes.

Subtribe Dendrobiinae with the genera Bulbophyllum (1,867), Dendrobium (1,509);

Subtribe Malaxidinae with the genera Alatiliparis (5), Crepidium (260), Crossoglossa (26), Crossoliparis (1), Dienia (6), Hammarbya (1), Hippeophyllum (10), Liparis (426), Malaxis (182), Oberonia (323), Oberonioides (2), Orestias (4), Stichorkis (8), Tamayorkis (1).

Liparis condylobulbon enlarged flower. This epiphyte and lithophyte orchid of humid South-East Asia forests, has inflorescences with 15-35 flowers of 4-5 mm. It belongs to the Malaxidinae subtribe where Liparis is by far the most numerous genus with 426 described species © Mazza

Tribe Cymbidieae

The tribe Cymbidieae subdivided in 10 subtribes has about 186 genera and more than 2000 species. It regroups terricolous or epiphytic species spreading in all the tropical regions of the World. Common characteristic is the sympodial posture and the presence of two pollinia.

– Subtribe Cymbidiinae with the genera Acriopsis (9), Cymbidium (71), Grammatophyllum (12), Porphyroglottis (1), Thecopus (2), Thecostele (1);

– Subtribe Eulophiinae with genera Acrolophia (7), Ansellia (1), Claderia (2), Cymbidiella (3), Dipodium (25), Eulophia (200), Eulophiella (5), Geodorum (12), Grammangis (2), Graphorkis (4), Imerinaea (1), Oeceoclades (38), Paralophia (2);

– Subtribe Catasetinae with the genera Catasetum (176), Clowesia (7), Cyanaeorchis (3), Cycnoches (34), Dressleria (11), Galeandra (38), Grobya (5), Mormodes (80);

– Subtribe Cyrtopodiinae with one only genus Cyrtopodium (47);

– Subtribe Coeliopsidinae with the genera Coeliopsis (1), Lycomormium (5), Peristeria (13);

– Subtribe Maxillariinae with the genera Anguloa (9), Bifrenaria (21), Guanchezia (1), Horvatia (1), Lycaste (32), Maxillaria (658), Neomoorea (1), Rudolfiella (6), Scuticaria (11), Sudamerlycaste (42), Teuscheria (7), Xylobium (30).

– Subtribe Oncidiinae

This subtribe counts almost 1,000 species and about 65 genera, distributed in tropical America, in the Caribbean and in Florida. Most of them are epiphytic, but some are terricolous. They are perennial, great and long-lived plants with short and robust pseudobulbs that may weigh even 1 kg or more.

The species of this tribe are important elements of neotropical flora and colonize areas going from the sea level up to 4,000 m of altitude in the Andes. The size of the flowers is quite variable and the various species are utilized by different pollinators. The rewards are nectar, oils and scents, but the mimicry is the most diffused pollination strategy. The chromosomic number goes from the lowest (2n=10) to the highest known in the orchids (2n=168).

The subtribe Oncidiinae includes the genera Aspasia (7), Brassia (64), Caluera (3), Capanemia (9), Caucaea (9), Centroglossa (5), Chytroglossa (3), Cischweinfia (11), Comparettia (78), Cuitlauzina (7), Cypholoron (2), Cyrtochiloides (3), Cyrtochilum (137), Dunstervillea (1), Eloyella (10), Erycina (7), Fernandezia (51), Gomesa (119), Grandiphyllum (7), Hintonella (1), Hofmeisterella (2), Ionopsis (6), Leochilus (12), Lockhartia (28), Macradenia (11), Macroclinium (42), Miltonia (12), Miltoniopsis (5), Notylia (56), Notyliopsis (2), Oliveriana (6), Oncidium (311), Ornithocephalus (55), Otoglossum (13), Phymatidium (10), Platyrhiza (1), Plectrophora (10), Polyotidium (1), Psychopsiella (1), Psychopsis (4), Pterostemma (3), Quekettia (4), Rauhiella (3), Rhynchostele (17), Rodriguezia (48), Rossioglossum (9), Sanderella (2), Saundersia (2), Schunkea (1), Seegeriella (2), Solenidium (3), Suarezia (1), Sutrina (2), Systeloglossum (5), Telipogon (205), Thysanoglossa (3), Tolumnia (27), Trichocentrum (70), Trichoceros (10), Trichopilia (44), Trizeuxis (1), Vitekorchis (4), Warmingia (4), Zelenkoa (1), Zygostates (22).

Ecuador and Peru epiphyte or terricolous, Cyrtochilim serrartum, tribe Cymbidieae, has about 3 m inflorescences and 6-7 cm waxy flowers © Giuseppe Mazza

Subtribe Stanhopeinae

This subtribe includes the genera Acineta (17), Braemia (1), Cirrhaea (7), Coryanthes (59), Embreea (2), Gongora (74), Horichia (1), Houlletia (9), Kegeliella (4), Lacaena (2), Lueckelia (1), Lueddemannia (3), Paphinia (16), Polycycnis (17), Schlimia (7), Sievekingia (16), Soterosanthus (1), Stanhopea (61), Trevoria (5), Vasqueziella (1).

Subtribe Zygopetalinae

Includes the genera: Aetheorhyncha (1), Aganisia (4), Batemannia (5), Benzingia (9), Chaubardia (3), Chaubardiella (8), Cheiradenia (1), Chondrorhyncha (7), Chondroscaphe (14), Cochleanthes (4), Cryptarrhena (3), Daiotyla (4), Dichaea (118), Echinorhyncha (5), Euryblema (2), Galeottia (12), Hoehneella (2), Huntleya (14), Ixyophora (5), Kefersteinia (70), Koellensteinia (17), Neogardneria (1), Otostylis (4), Pabstia (5), Paradisanthus (4), Pescatoria (23), Promenaea (18), Stenia (22), Stenotyla (9), Vargasiella (1), Warczewiczella (11), Warrea (3), Warreella (2), Warreopsis (4), Zygopetalum (14), Zygosepalum (8).

Like tribe Malaxideae also tribe Cymbidieae has more than 2000 species. Here Brazil Gomesa radicans, with its white crescent shaped flower © Giuseppe Mazza

Tribe Epidendreae

It is the greatest tribe of the subfamily Epidendroideae. It regroups more than 8,000 cosmopolitan species. It includes one of the most numerous genera of the Neotropics: Epidendrum, together with a heterogeneous group of small plants, the Pleurothallidinae. The species of this tribe display various types of reproductive strategies due to the shape of the flower as well as due to the modalities of pollination.

For instance, in Cattleya the flowers have transformed in traps, they imitate the shape of the female of the pollinating insect or emit their scent during the reproductive season or they create sacs or spurs rich of sugary secretions. Encyclia and Protechea have fleshy-waxy flowers to attract bees and wasps; Isochilus has thin stems, similar to canes, with flat leaves, distichous, narrow and small sessile flowers carried at the apex of the cane. The base of the bulb is incongrous and the small tubular flowers are united in racemose inflorescences to attract the hummingbirds. In Stelis cypripedioides that has small flowers, fleshy, resupinate, with sepals patially merged and pubescent inside, have been discovered crystalline deposits (presumably calcium oxalate) that play a rôle in the visual signalling.

According to the current systematics, the tribe Epidendreae is formed by six subtribes: Agrostophyllinae, Calypsoinae, Bletiinae, Ponerinae, Pleurothallidinae, Laeliinae.

Epidendrum atacazoicum, E. hugomedinae and E. macrum. In the Epidendreae tribe, rich of 8000 species, stands out genus Epidendrum with 1413 species © Giuseppe Mazza

Furthermore, with the recent addition of the genus Earina, of Asian origin, and of the North American Calypso, the tribe is not any more exclusive of the Neotropics as was previously thought. Also in the Epidendreae, the most evident element of the flower is the labellum that shows a clear diversity of shape and colour. Another important element is the column, formed by androecium, stigma and style with only one stamen with pollen granules variously aggregated in pollinia. Commonly, the position of the labellum and of the column are important for obliging the pollinator to approach the flower in way that the pollinia are placed in correspondence to the pollinator. The pollinia can change orientation after the removal done by the pollinator so that it is placed correctly upon the next visited flower. The pollinia have acquired a remarkable complexity among the Epidendreae: in fact , they have different appendages like the viscidium (or retinaculum) that adheres to the pollinator, replaced, in some species, by a liquid on the rostellum and pollinia with floury or elastic caudicles. Anoother important characteristic is the cap of the anther that covers the pollinia, and in most species, this falls following its removal done by the pollinator.

According to the phylogenetic studies, it is thought that the position of the anther, erect and parallel to the axis of the column is a primitive condition as observed in many Orchidoideae whilst most of the Epidendroideae are a derived condition. It has been seen that the anther is erect during the initial development and then it bends from 90° to 120° due to elongation of the column, in way it stops, like a cap, on the apex of the column. Hence, it assumes a different position, and this is considered as the most important final character of the subfamily Epidendroideae.

Cattleya maxima and Cattleya leuddemanniana with fruits. The Cattleya genus belong with 113 species to subtribe Laeliinae. The flowers at times are deceptive traps for insects, imitating the pronube shape or its scent. Some to seduce them often offer a tempting meal, with sacs and spurs rich of sugary secretions © Giuseppe Mazza

Analogously, in five of the six subtribes of the Epidendreae, the anther has been identified as derived character (Xynapomorphy), that is obtained with the reorientation during the first phases of the growth of the anther or due to the extension of the column and the inflection of the mature anther. During the last phase of development. The degree of flection varies among the species and the greatest inversion is found in those pollinated by birds.

The Epidendreae number about 80 genera and more than 8,000 species divided in 6 subtribes.

Subtribe Bletiiae with the genera Basiphyllaea (7), Bletia (33), Chysis (10), Hexalectris (10);

Subtribe Laeliinae with the genera Acrorchis (1), Adamantinia (1), Alamania (1), Arpophyllum (3), Artorima (1), Barkeria (17), Brassavola (22), Broughtonia (6), Cattleya (113), Caularthron (4), Constantia (6), Dimerandra (8), Dinema (1), Domingoa (4), Encyclia (165), Epidendrum (1413), Guarianthe (4), Hagsatera (2), Homalopetalum (8), Isabelia (3), Jacquiniella (12), Laelia (23), Leptotes (9), Loefgrenianthus (1), Meiracyllium (2), Microepidendrum (1), Myrmecophila (10), Nidema (2), Oestlundia (4), Orleanesia (9), Prosthechea (117), Pseudolaelia (18), Psychilis (14), Pygmaeorchis (2), Quisqueya (4), Rhyncholaelia (2), Scaphyglottis (69), Tetramicra (14);

Encyclia garciana and E. cochleata belong to the Laeciinae subtribe. The genus Encyclia flowers, that has 165 species, are fleshy-waxy to attract bees and wasps © G. Mazza

Subtribe Pleurothallidinae with the genera Acianthera (118), Anathallis (152), Andinia (13), Barbosella (19), Brachionidium (75), Chamelophyton (1), Dilomilis (5), Diodonopsis (5), Draconanthes (2), Dracula (127), Dresslerella (13), Dryadella (54), Echinosepala (11), Frondaria (1), Kraenzlinella (9), Lepanthes (1085), Lepanthopsis (43), Masdevallia (589), Myoxanthus (48), Neocogniauxia (2), Octomeria (159), Pabstiella (29), Phloeophila (11), Platystele (101), Pleurothallis (551), Pleurothallopsis (18), Porroglossum (43), Restrepia (53), Restrepiella (2), Sansonia (2), Scaphosepalum (46), Specklinia (135), Stelis (879), Teagueia (13), Tomzanonia (1), Trichosalpinx (111), Trisetella (23), Zootrophion (22);

Subtribe Ponerinae with the genera Helleriella (2), Isochilus (13), Nemaconia (6), Ponera (2);

Subtribe Calypsoinae with the genera Aplectrum (1), Calypso (1), Changnienia (1), Coelia (5), Corallorhiza (11), Cremastra (4), Dactylostalix (1), Danxiaorchis (1), Ephippianthus (2), Govenia (24), Oreorchis (16), Tipularia (7), Yoania (4);

Subtribe Agrostophyllinae with the genera Agrostophyllum (100), Earina (7).

Spathoglottis plicata and Ascidiana longifolia belong to the so-called superior Epidendroideae, respectively to Colliabeae and Podochillae tribes © Giuseppe Mazza

Tribe Collabieae

This tribe includes the genera canthephippium (13), Ancistrochilus (2), Ania (11), Calanthe (216), Cephalantheropsis (4), Chrysoglossum (4), Collabium (14), Diglyphosa (3), Eriodes (1), Gastrorchis (8), Hancockia (1), Ipsea (3), Nephelaphyllum (11), Pachystoma (3), Phaius (45), Pilophyllum (1), Plocoglottis (41), Risleya (1), Spathoglottis (48), Tainia (23).

Tribe Podochileae

It includes the genera Appendicula (146), Ascidieria (8), Bryobium (8), Callostylis (5), Campanulorchis (5), Ceratostylis (147), Conchidium (10), Cryptochilus (5), Dilochiopsis (1), Epiblastus (22), Eria (237), Mediocalcar (17), Mycaranthes (36), Notheria (15), Octarrhena (52), Oxystophyllum (36), Phreatia (211), Pinalia (105), Poaephyllum (6), Podochilus (62), Porpax (13), Pseuderia (20), Ridleyella (1), Sarcostoma (5), Stolzia (15), Thelasis (26), Trichotosia (78).

Masdevallia davisii belongs to the subtribe Pleurothallidinae © Giuseppe Mazza

Tribe Vandeae

This tribe contains about 2,000 species with more than 150 genera.

They are pantropical epiphytes, rarely lithophyte, and are found in tropical Asia, in the Pacific islands, in Australia and in Africa. Many of these orchids are important on the horticultural point if view, in particular Vanda and Phalaenopsis.

They have mostly stems with monopodial growth, even if, in some genera, the growth can be sympodial (i.e. Hederorkis and Polystachya).

The leaves have a fleshy consistency, but in some species they can be absent (i.e. Campylocentrum, Dendrophylax).

The flowers, united in racemose axillaty inflorescences, are very perfumed, especially during the night, and are variously coloured. They can be white (Angraecum atlanticum Stévart & Droissart), white-greenish (Angraecum sesquipedale, Thouars), yellow, orange (Ascocentrum miniatum (Lindl.) Schltr., Ossiculum aurantiacum P.J.Cribb & Laan), blue (Vanda coerulea Griff. ex Lindl.), pink, violet or even red in Renanthera philippinensis (Ames& Quisumb.) L.O. Williams.

The systematics of this tribe is still mainly based on the morphology of the flower that, however, can be the outcome of convergence phenomena and consequently not always valid for the phylogenetic relations.

The extant molecular proofs, in particular for the relations among the membres of the tribe Vandeae, are limited and in need of further deepening.

The tribe is divided in 4 subtribes with more than 2,000 species.

– Subtribe Adrorhizinae with the genera Adrorhizon (1), Bromheadia (30), Sirhookera (2);

– Subtribe Polystachyinae with the two genera Hederorkis (2), Polystachya (234);

Subtribe Aeridinae with the genera Acampe (8), Adenoncos (17), Aerides (25), Amesiella (3), Arachnis (14), Biermannia (11), Bogoria (4), Brachypeza (10), Calymmanthera (5), Ceratocentron (1), Chamaeanthus (3), Chiloschista (20), Chroniochilus (4), Cleisocentron (6), Cleisomeria (2), Cleisostoma (88), Cleisostomopsis (2), Cottonia (1), Cryptopylos (1), Deceptor (1), Dimorphorchis (5), Diplocentrum (2), Diploprora(2), Dryadorchis (5), Drymoanthus (4), Dyakia (1), Eclecticus (1), Gastrochilus (56), Grosourdya (11), Gunnarella (9),Holcoglossum (14), Hymenorchis (12), Jejewoodia (6) , Luisia (39), Macropodanthus (8), Micropera (21), Microsaccus (12), Mobilabium (1), Omoea (2), Ophioglossella (1), Papilionanthe (11), Papillilabium (1), Paraphalaenopsis (4), Pelatantheria (8), Pennilabium (15), Peristeranthus (1), Phalaenopsis (70), Phragmorchis (1), Plectorrhiza (3), Pomatocalpa (25), Porrorhachis (2), Pteroceras (27), Renanthera (20), Rhinerrhiza (1), Rhinerrhizopsis (3), Rhynchogyna (3), Rhynchostylis (3), Robiquetia (45), Saccolabiopsis (14), Saccolabium (5), Santotomasia (1), Sarcanthopsis (5), Sarcochilus (25), Sarcoglyphis (12), Sarcophyton (3), Schistotylus (1), Schoenorchis (25), Seidenfadenia (1), Seidenfadeniella (2), Singchia (1), Smithsonia (3), Smitinandia (3), Spongiola (1), Stereochilus (7), Taeniophyllum (185), Taprobanea (1), Thrixspermum (161), Trachoma (14), Trichoglottis (69), Tuberolabium (11), Uncifera (6), Vanda (73), Vandopsis (4);