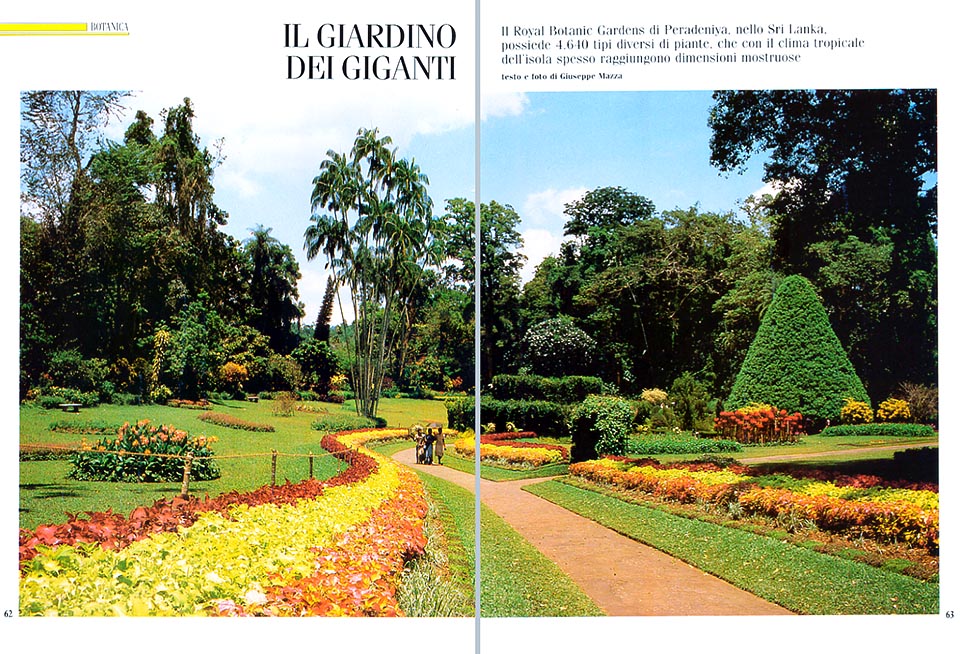

The garden of giants. The Royal Botanic Gardens of Peradeniya, in Ceylon, have 4.640 different kinds of plants which, due to the tropical climate of the island, often reach monstrous dimensions. 60 hectares and 600.000 visitors every year. A Ficus bejamina of 1.500 m2.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

Sixty hectares, more than 600.000 visitors per year, practically,

an immense greenhouse where the most difficult apartment plants blossom and assume gigantic dimensions.

The origins of the Royal Botanic Gardens of Peradeniya, a hamlet 6 km south of Kandy, in Sri Lanka, date back to the year 1371, the time of the Singhalese sovereign Wickrema Bahu III.

It was a royal garden till the beginning of 1800, and in February 1822, under the British rule, it became an experimental botanical garden, for testing, in the warm-humid climate of Ceylon, profitable cultivations, such as the gum and the spices.

But its first director, Alexander Moon, developed, at once, also the botanical aspect, starting a major systematic work: the “Catalogue of the Indigenous and Exotic Plants Growing in Ceylon”, with the description, remarkable for those times, of even 1.127 native plants.

Nowadays, the garden is in possession of 4.640 “Taxa”, that is various kinds of plants, between botanical species and cultivars.

At the entrance, they maintain that it can be visited in one hour drive, and suggest half a day on foot, but some days are needed only to “learn how not to get lost”, and in one week, you will be hardly able to see it all.

Got through the gate and the rowdy barrage of pedlars of spices and neck laces, we feel something like a sensation of diving in the past, to be visiting an “old lady”, perhaps somewhat in decline, but still rich of charm.

At the base of the trunks, memorial signboards remind that in 1901 King George V planted, along with the Queen Mary, the Cannonball Tree (Couroupita guianensis), that in 1891, the czar of Russia, planted a Ceylon Ironwood (Mesua ferrea), with very hard wood, heavier than water, or that Eduard VII, in 1875, gave as a present a “Bo tree” (Ficus religiosa), the sacred plant under which Buddha reached the illumination.

Some Singhalese stop, praying. I try not to disturb them, and I realize that all the garden resembles to a huge open air temple, a green shrine, where the man looks retrenched by the gigantic secular trees and by the dignified harmony of the drives.

Each plant, great or small, gains, itself, a value, and it seems almost a crime to walk over the humble flowers of the Sensitive plant (Mimosa pudica), which sprout between the grass of the wide English-cut lawn.

Groups of gardeners mow it continuously, by hand, with cadenced strokes of palm leaves. A decorous poverty of which the tourists do not laugh: they look, admired, in silence, almost uneasy, and do not dare to throw any rubbish, or to write anything on the trees as a souvenir.

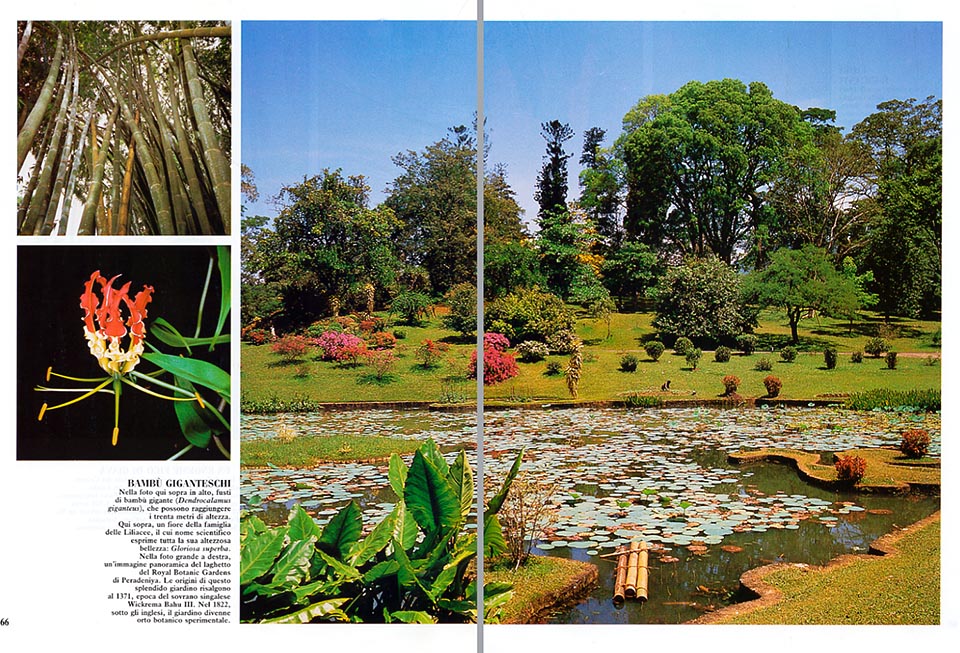

The huge green rings of the Giant Bamboos (Dendrocalamus giganteus), which, elsewhere, would have attracted hordes of engravers, here are incredibly untouched.

This graminae, even 30 metres tall, is the greatest existing “grass”, and during the rainy season, in June-July, grows up at the incredible speed of 30 cm per day.

In Sri Lanka it is used to build up scaffoldings, pots and canalizations, and, in war time, to oblige the prisoners to talk: they are cruelly tied over the buds, and run through, slowly, if they do not “speak out”, by the growing stems.

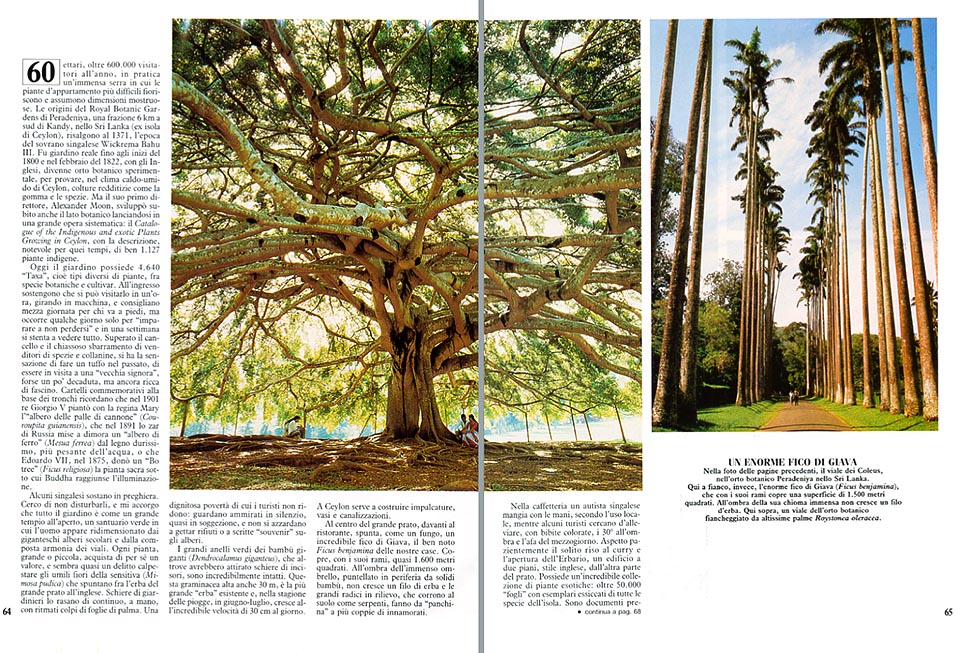

At the centre of the vast lawn, in front of the restaurant, stands, like a mushroom, an incredible Weeping Fig, the well known Ficus Benjamina, of our houses.

It covers, with its branches, almost 1.600 m2. In the shade of its immense umbrella, propped up, in periphery, by strong bamboos, does not grow a single blade of grass, and its big roots, in relief, which run on the ground like snakes, act as “benches”, to several pairs of sweethearts.

In the cafeteria, a Singhalese driver eats, using his hands, in accordance with the local habits, while some tourists try to relieve, with coloured drinks, the 30° in the shade and the sultriness of noon time.

I await patiently my usual rice and curry, and the opening of the Herbarium, a two-story building, English style, on the other side of the lawn.

It holds an incredible collection of exotic plants: more than 50.000 “sheets”, with dessicated specimen of all the species of the island. They are valuable documents, full of fascination, of the time when the photography did not exist, with notes done, with China ink, by the English botanists.

In the time of the computers, not much has changed in Sri Lanka, the colour films, difficult to be developed, are still a luxury, and, joking on my several Hasselblads, they introduce me to Mr. Premasuriya, the “living camera” of the National Herbarium.

He reproduces accurately, with pencils and water-colours, the most complicated details and the colours of his “pictures” do not fear the warmth, the humidity and the strain of the time.

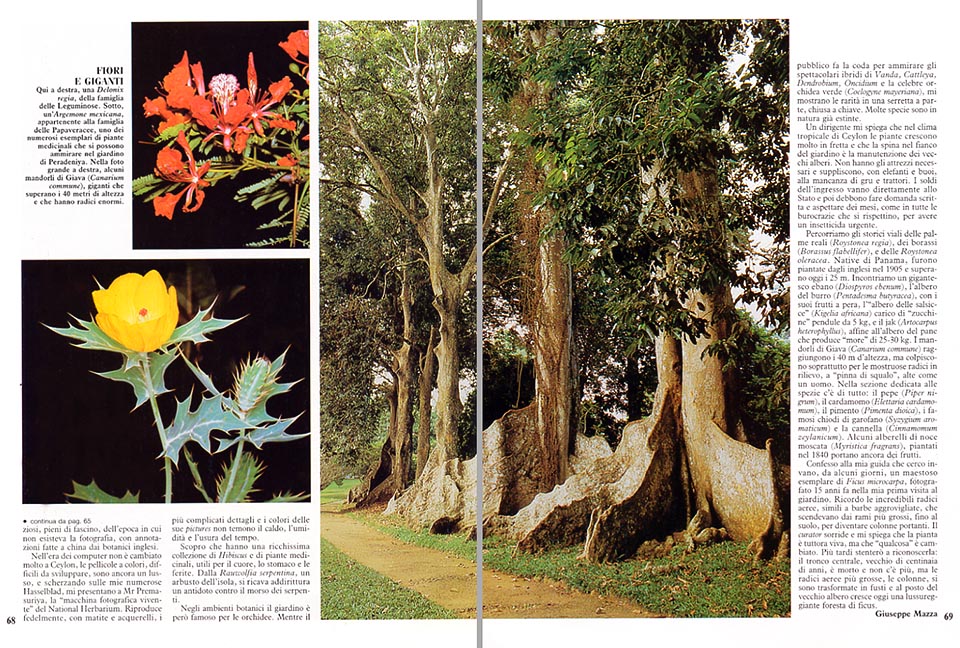

I discover that they have a very rich collection of Hibiscus, and of medicinal plants, useful for the heart, the stomach and the wounds. From the Rauwolfia serpentina, a shrub of the island, they even extract an antidote against the bite of snakes.

In the botanical milieu, the garden is, however, famous for the orchids. While the public is queueing for admiring the spectacular hybrids of Vanda, Cattleya, Dendrobium, Oncidium and the famous Green Orchid (Coelogyne mayeriana), they show me the rarities in a different, small greenhouse, which is kept locked. Many species are, in the wild, already extinct.

A manager explains to me that in the tropical climate of Sri Lanka, the plants grow up very quickly, and the main problem of the gardens stands in the proper up keeping of the old trees.

They do not have the necessary tools, and they compensate the lack of cranes and tractors, with elephants and oxen.

The money received from the admission tickets goes straight to the State, and then they have to apply in writing, and then wait for months, alike all respectable bureaucracies, for getting an urgent insecticide.

We go along the historical drives of the Royal Palm (Roystonea regia), of the Toddy Palms(Borassus flabellifer), and of Roystonea oleracea. Native of Panama, they were planted by the English in 1905, and now are more than 25 metres tall. We meet a gigantic Ebony (Diospyros ebenum), the Butter Tree (Pentadesma butyracea), with its pear-like fruits, the Sausage Tree (Kigelia africana), loaded of 5 kg pendulous “courgettes”, and the Jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus), similar to the Bread Tree, which produces berries weighing 25-30 kg each.

The Java almonds (Canarium commune), reache the 40 metres of height, but they strike mainly for the monstrous roots in relief, resembling to “shark fins”, as tall as a man. In the section dedicated to the spices, there is everything: the Pepper (Piper nigrum), the Cardamom (Elettaria cardamomum), the Allspice (Pimenta dioica), the famous Cloves (Syzygium aromaticum), and the Cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanicum).

Some small trees of Nutmeg (Myristica fragrans), planted in 1840, still bear fruits.

I tell my guide that I am looking, in vain, since some days, for a majestic specimen of Ficus microcarpa, which I had taken in photo 15 years before, during my first visit to the garden.

I remember the incredible aerial roots, similar to entangled beards, which were coming down from the largest branches, up tto the ground, thus becoming load-bearing columns. The “curator” smiles and explains to me that the plant is still alive, but that “something” has changed.

Later on, I will have difficulties to recognize it: the central trunk, several hundreds of years old, has passed away, and is not there any more, but the aerial roots are bigger, the columns have transformed in trunks, and, in lieu of the old tree, now there is a luxuriant forest of Ficus.

SCIENZA & VITA NUOVA – 1988