Together with shape and colour, perfume is one of the weapons used in the vegetable kingdom to attract insects, even in a range of several kilometers.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

The first terrestrial plant was not perfumed.

The ferns were not so, as they were entrusting their progeny to the spores and the water, with microscopic small reproductive plants and spermatozoa which were reaching the destination by swimming, and also the mosses were not, even if from their humid small cushions comes out a typical odour of wood.

By sure, also in the forests of the Mesozoic, this odour was not missing: stench of dead plants, of dead bodies, which were spreading around, as it happens nowadays, their unmistakable calls.

Ancient crustaceans, molluscs, flies and coleoptera were rushing, attracted by the liquids to be sucked, and by the tissues softened by the bacteria, but the first flower was not yet born, and the plants in the van, those which had invented the pollen, were entrusting it to the wind.

They had realized some revolutionary “mini spatial capsules”, from where, once reached the stigma, the masculine element was coming out, like an astronaut, through a tunnel, fecundating the ovule without any contact with the outer world.

And in order to push them farther, some species, like the conifers, had applied to them some air bags which were carrying them high in the sky, like hang-gliders.

The pollen granules were going up, till 5.000 metres of altitude, and even more, with the risk of losing, under the ultra-violet rays, their germinative power, but then they were landing at hundreds of kilometres far away, effecting fantastic exchanges of genes between very distant populations.

Most important, on the other hand, was the risk of missing the target. Almost all the Charming Princes, which were leaving hibernated in their nice space capsules, did not wake up at all any more.

For waking up, they needed the kiss of the “princess of the stigma” (in this “tale”, the roles, are, oddly, reversed), but the chances of receiving it were of one or two of a million.

Nevertheless, the trees were not giving in, and like the American bombers of the last war, were compensating with the quantity the inaccuracy of their launching. Still now, in Europe, one square centimetre of land receives about 27.000 granules of pollen per year, and at the time that the wind was the only means of transportation, their number had to be really impressive.

“There must be well a less demanding and more accurate system”, some plants were thinking, and, as the sky was full of coleoptera, a cycadacea had the idea to exploit them.

Even if it was going on in giving the wind billions of granules of pollen, it rendered them sticky, and did perfume them intensely with the usual odours of the wood. The coleopteron was coming, attracted by the aroma; instead of the rotten vegetables, it found strange small spheres with the same taste, and after having eaten a few of them, was leaving, satisfied, loaded of “space capsules”, which could, in this way, reach more easily the destination.

They were not, by sure, sweet fragrances, but, anyway, the were “perfumes”.

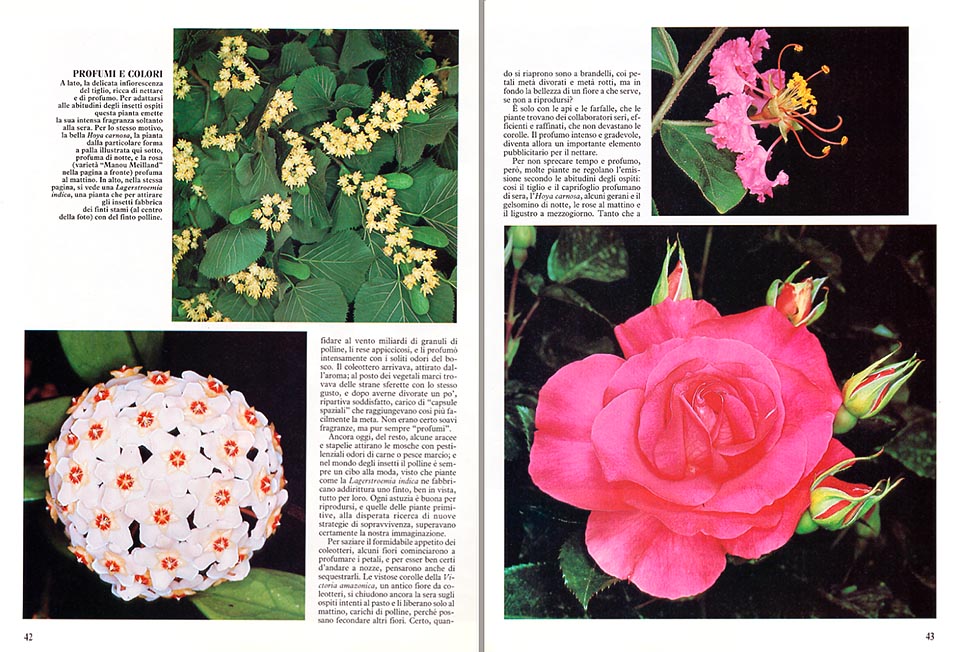

Still now, on the other hand, some Araceae and Stapelia attract the flies with stinking odours of rotten meat or fish; and in the world of the insects, the pollen is always a food in fashion, as plants like the Lagerstroemia indica even fabricate one false, well in sight, all for them. Every ruse is good for the reproduction, and those of the primitive plants, at the desperate research of new strategies of survival, were surely overcoming our imagination.

For satiating the formidable appetite of the coleoptera, some flowers began to perfume the petals, and in order to be quite sure to get married, thought also to kidnap them.

The showy corollas of the Victoria amazonica, an old coleoptera flower, still close, stoically, the evening, on the guests intent upon the meal, and release them only in the morning, loaded of pollen, so that they can fecundate other flowers. By sure, when they open again, they are in tatters, with the petals half eaten, and half broken, but after all what’s the use of the beauty of a flower, if not for its reproduction, and once reached the purpose, it has no meaning at all.

It is only with the bees and the butterflies, that the plants get serious, efficient and refined collaborators, which do not devastate the corollas.

The perfume, always more intense and pleasant, becomes then an important advertising element for the nectar: the rich and bloodless meal invented by the flowers for the postmen of the pollen. And if the corolla is the signboard of the restaurant, the perfume is the background music, or the odour of the roast, if it’s matter of a small country inn.

We shall never know if in the meadow, exist one or more stars restaurants for insects, by sure, the competition is much, and each species has its own menu and its own clients.

In order not to waste time and perfume, many plants even adjust their emission, depending on the habits of the guests.

And so, the lime-tree and the honey-suckle are perfumed in the evening, the Hoya carnosa, some geraniums and the jasmine, the night, the roses, the morning, and the privet, by noon.

So that a botanist had the idea of creating a watch for the blind, based on the fragrances of the flowers.

Surely, the insects perceive the perfumes in a much more intense and different way than is: we might say that with their antennas they can see them, almost touch them, and to the male of the silkworm it suffices only one molecule of Bombykol, the substance emitted by the female, to locate with precision its position, even if at a distance of several kilometres.

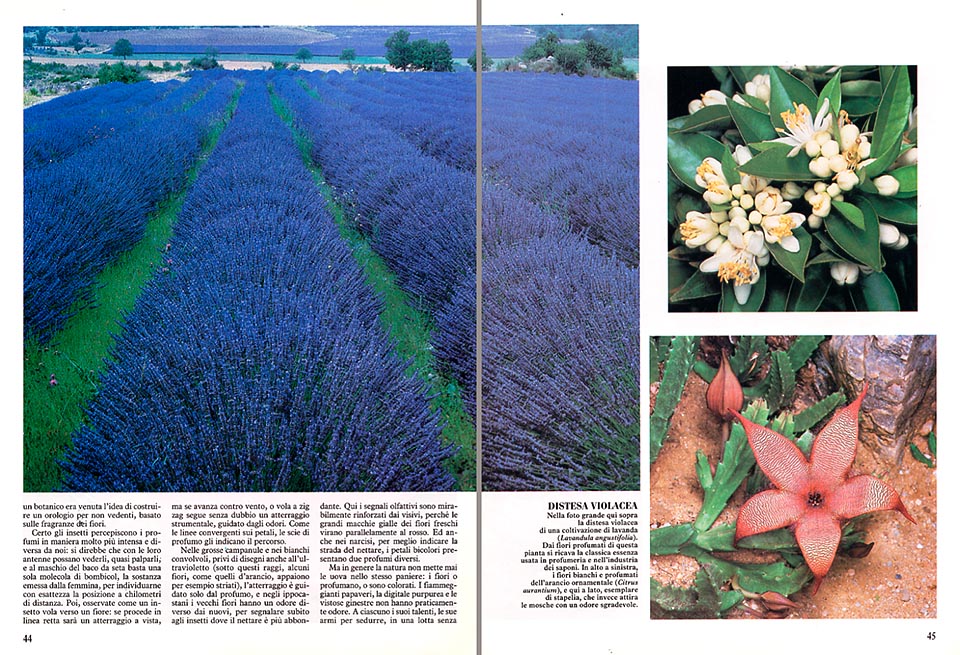

Then observe how an insect flies towards a flower. If it proceeds following a straight line, the landing will be at sight, but if it goers ahead on the wind, or flies zigzagging, is doing, without any doubt, an instrumental landing, guided by the odours.

Like the converging lines on the petals, the tracks of perfume indicate the way, and what it must do, so that the pollination takes place in the right way.

In the big bell flowers, and in the white convolvuluses, lacking of drawings even at the ultra violet (under these rays, some flowers, like those of the orange, look, for instance, striped), the landing is guided only by the perfume, and in the horse-chestnuts the old flowers have an odour different from the new ones, to inform at once the insects as to where the nectar is more copious.

Here, the olfactory signals are admirably reinforced by the visual ones, because the wide yellow dots of the fresh flowers are turning, in a parallel way, to the red. And also in the narcissi, for better indicating the way of the nectar, the two-coloured petals present two different perfumes.

But, usually, the nature never places the eggs in the same basket: the flowers either are perfumed, or are coloured.

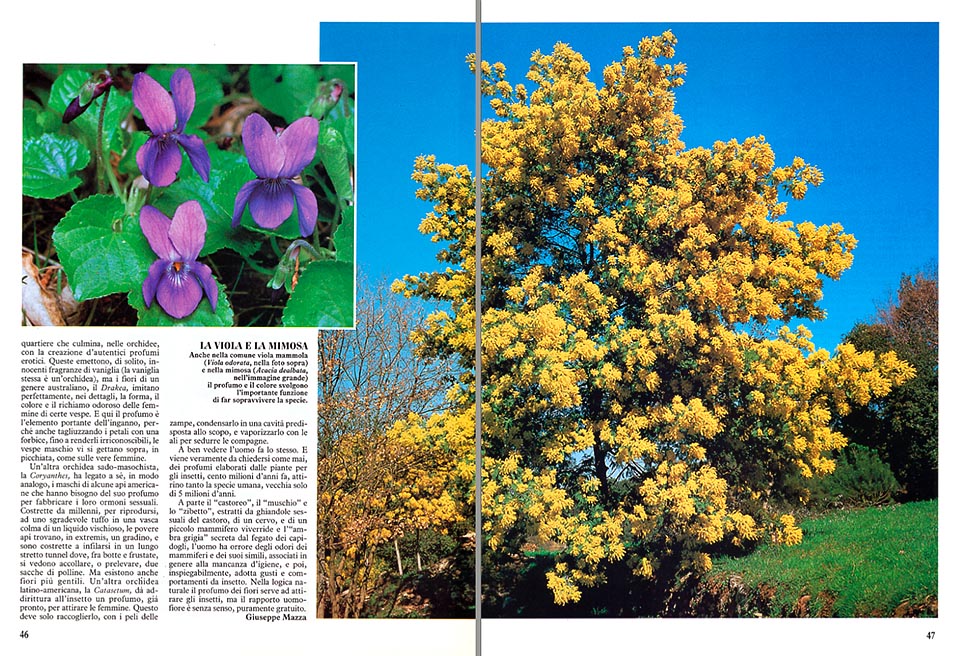

The blazing poppies, the foxglove and the showy brooms do not have, practically, any odour. Each one has its own gifts, its weapons for seducing, in a struggle without quarters, which culminates, in the orchids, with the creation of authentic erotic perfumes, for “the insect who has never to ask”.

These emit, normally, innocent fragrances of vanilla (the vanilla itself, is an orchid), but the flowers of an Australian genus, the Drakea, imitate perfectly, in the details, shape, colour and the odorous call of the females of certain wasps.

And here the perfume is the load bearing element of the deceit, because, even cutting the petals with the scissors, till to render them not recognizable, the male wasps throw themselves over them, diving, as they would do on real females.

Another sadomasochist orchid, the Coryanthes, has tied to itself, in a similar way, the males of some American bees which need its perfume for developing their sexual hormones. Obliged, since millennia, for reproducing, to an unpleasant dive in a basin full of a viscous liquid, the poor bees find, in extremis, a step, and are compelled to slip into a long, narrow, tunnel where, between blows and lashes, get, or are taken, two bags of pollen.

But also flowers more gentle do exist. Another Latin American orchid, the Catasetum, gives even to the insect a perfume, already prepared, for attracting the females. This has only to pick it up, with the hair of the legs, to condensate it in a cavity arranged beforehand for this purpose, and to vaporize it on the wings, to seduce the females.

If we look well, the man is doing the same thing. And we can really ask ourselves how, some perfumes elaborated by the plants for the insects, hundred million years ago, attract so much the mankind, which is only five million years old.

Apart the “Castoreum”, the “Musk” and the “Civetone”, extracted from the sexual glands of the beaver, of a deer and of a wild cat, and the “Grey Amber”, secreted by the liver of the sperm whales, the man is horrified by the odours of the mammals and of his likes, associated normally to the lack of hygiene, and then, inexplicably, adopts tastes and behaviours typical of the insects.

In the natural logic, the perfume of the flowers is of use for attracting the insects, but the relationship man-flower is absurd, purely gratuitous, even if, judging from the prices of the perfumes, this “gratuitousness” has not lasted long time.

SCIENZA & VITA NUOVA – 1989