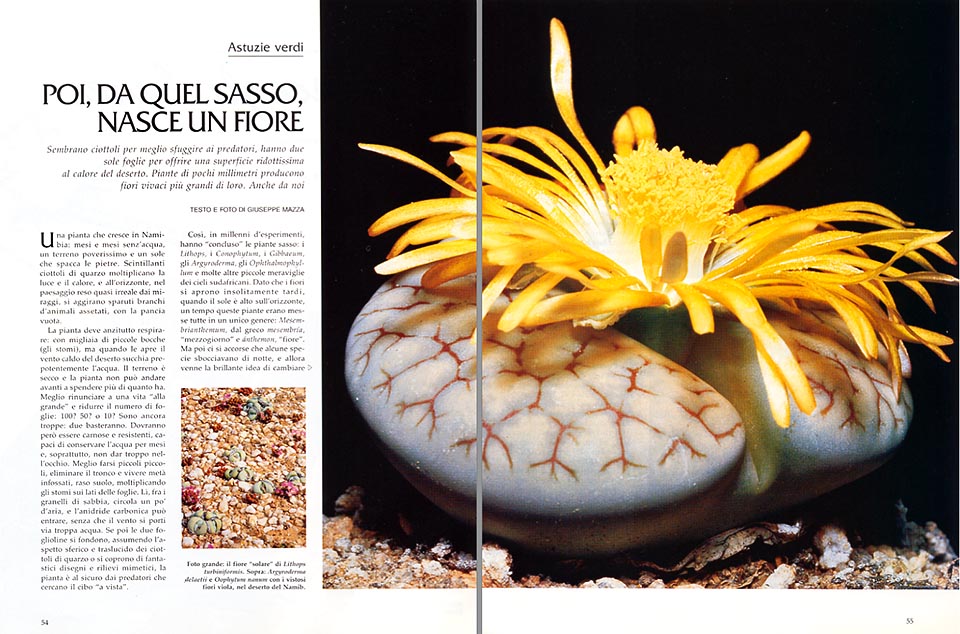

And then from a stone a flower blossoms. They resemble pebbles to avoid predators. They have only two leaves to offer the lowest surface to the heat of the desert. Plants few millimetres big they produce flowers, of bright colours, which are bigger than themselves. How to cultivate them. Fruits are “ intelligent ” capsules which open only when it rains.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

Let us imagine to be a plant, and to be growing up in Namibia: months and months without any water, a very poor soil and a blazing sun. Glittering quartz pebbles multiply the light and the heath, and on the horizon, in the landscape rendered almost unreal by the mirages, meagre herds of thirsty animals going around, the belly empty.

We have, first of all, to breath, as the plants do, of course, with thousands of small mouths, the stomata, but, when we open them, the hot wind of the desert is sucking, overbearingly, the water.

The ground is dry, and we cannot go ahead in spending more than what we have. Better to renounce to a life in “grand scale”, and reduce the number of leaves: 100?, 50?, or 10?

No, no, they are still too many: two will suffice! They will have to be, however, pulpy and resistant, capable to keep the water for months, and, above all, not to strike the eye too much.

Better to become small, small, eliminate the stem and live half sunken, close to the ground, multiplying the stomata on the sides of the leaves. There, between the grains of sand, there is some air, which is circulating, and the carbon dioxide can enter, without the wind taking off too much water.

If then, the two small leaves join, assuming the spherical and translucent aspect of the quartz pebbles, or they cover up with fantastic drawings and mimetic relieves, we are even safe from the predators, which look for the food “at sight”.

In this way, in experiments which have lasted for millennia, have “concluded” the pebble plants: the Lithops, the Conophytum, the Gibbaeum, the Argyroderma, the Ophthalmophyllum and many other small wonders of the South African skies.

As the flowers open unusually late, when the sun is high on the horizon, time ago, these plants were placed in a unique genus: Mesembrianthemum, from the Greek mesembria, “midday”, and anthemon, “flower”. But, later on, they realized that some species were blossoming during the night, and then the brilliant idea came to change the name from Mesembrianthemum to Mesembryanthemum, from mésos, “central”, émbryon, “embryo”, and anthemon, “flower”.

Without any traumata and showy changes, altering the “i” into “y”, the scientific rigour was saved.

But, while they were proceeding in the explorations, the number of the species was increasing: 500, 1.000, 2.000 and more. At a certain moment, as it happens for the too “heavy” stocks quoted in Wall Street, the botanists were compelled to effect a “split”, and in 1973, the enormous group was, finally, divided into 125 new genera.

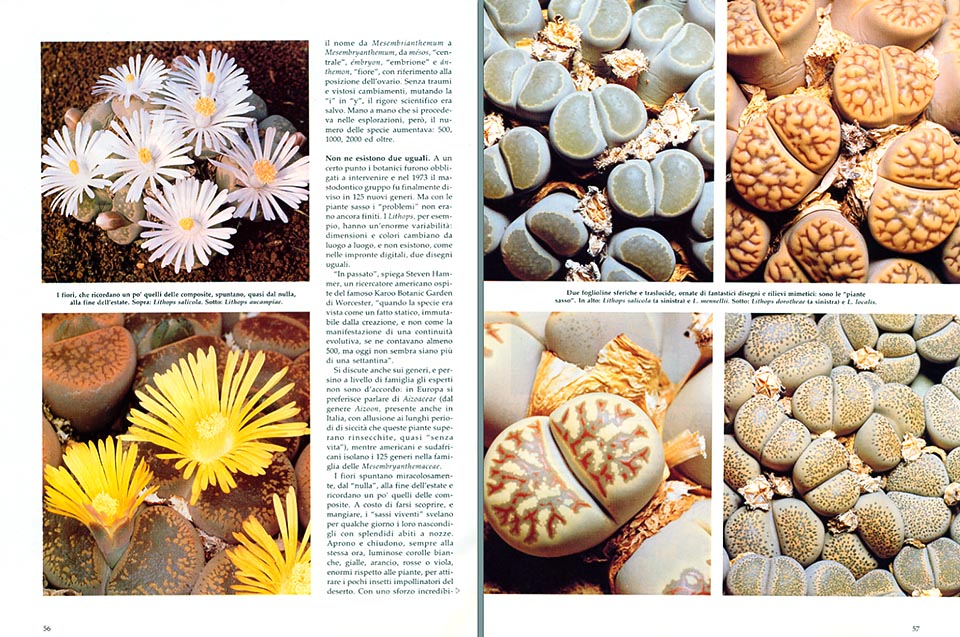

But, with the pebble plants, the “problems” were not yet over. The Lithops, for instance, have a great variability: dimensions and colours change depending on the location, and do not exist, as it happens for the fingerprints, two identical drawings.

In the past, Steven Hammer, an American researchers, guest of the famous Karoo Botanic Garden of Worchester, explains to me, when the species was considered as a static event, not changeable since the creation, and not as the manifestation of an evolutionary continuity, they were counting at least 500 of them, but nowadays, it seems that they are not more than 70.

They discuss also about the genera, and even at the level of family, the experts are in disagreement: In Europe, they prefer to talk of Aizoacea (from the genus Aizoon, present also in Italy, alluding to the long periods of drought which these plants overcome withered, almost “lifeless”), whilst Americans and South Africans isolate the 125 genera of the “split”, in the family of the Mesembryanthemaceae.

The flowers come out, miraculously, from the “nothing”, the the end of summer, and somewhat recall those of the asteraceae.

At the cost of being discovered, and eaten, the “living stones”, disclose for some days their hiding-places, with splendid wedding dresses. They open and close, always at the same time, bright white, yellow, orange, red or violet corollas, enormous, if compared to the plants, to attract the few pollinating insects of the desert.

With an incredible effort, the Conophytum minusculum, casts out from a little body of only 5-8 mm, showy red flowers of a diameter of 13-14 mm, and, usually, every “stone” has its regular guest, of which it knows very well the habits. It knows that early in the morning the insects sleep, and, just not to incur in any unnecessary risk, it opens late, in the hours when the pollinating species is active.

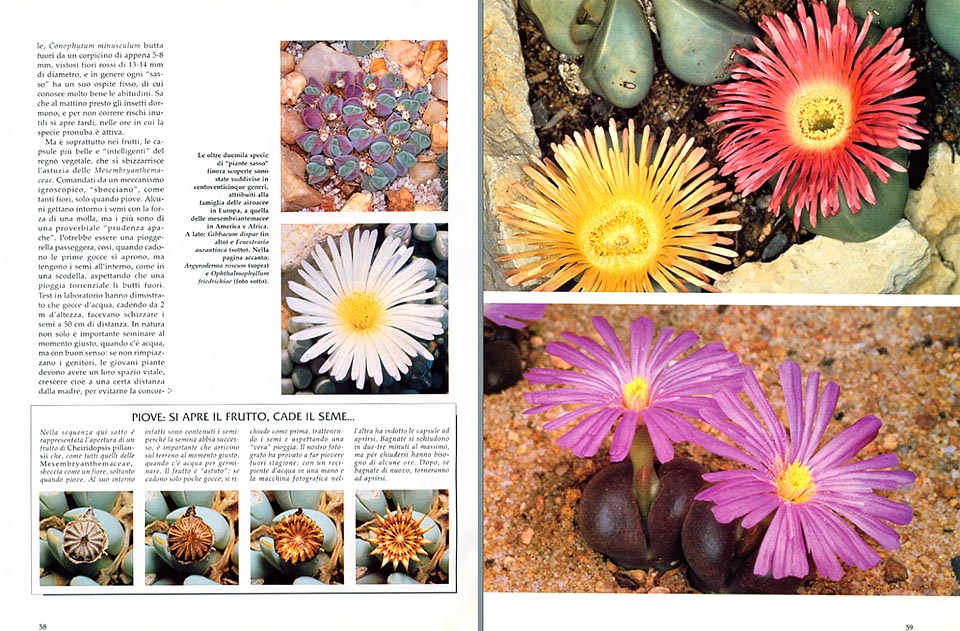

But it is chiefly in the fruits, the most beautiful and “intelligent” capsules of the vegetable kingdom, that the shrewdness of the Mesembryanthemaceae unfetters. Controlled by an hygroscopic mechanism, they “blossom”, like many flowers do, only when it rains. Some of them throw around the seeds with the strength of a spring, but most of them hold a proverbial patience, recalling us that of the Apaches.

“It might be a transient light rain”, they think, and when the first drops fall, they open, but keeping the seeds inside, like in a bowl, waiting for a torrential rain to throw them out.

Laboratory tests have proved that drops of water, falling from a height of two metres, made the seeds to spring up to 50 cm of distance. In the wild, it is important not only to sow at the right moment, when there is water, but with common sense: if they do not replace the parents, the young plants must have a personal vital space, that is, to grow at a certain distance from the mother, in order to avoid its competition.

Other capsules, not less cunning, use the “technique of the flush”: they fill up of water, till when they burst, and the water, then, pours out, in one go, through special small ducts, more or less choked up of seeds. In this way, they are not thrown out all together, but dispersed little by little, by successive showers, with more possibilities of success.

And if the rain ceases at once, and the sun comes back?

If the first drops are a false alarm, then, unique case in nature, the fruit closes again, perfectly, and waits for better days.

You will see, if you water them, they open at once, Mr. Busy Wiese, an expert in succulent plants of Vanrhynsdorp, owner of two estates literally covered of succulent plants, had told me.

You take the road N7, direction Springbok, had been his last words, and after 20 Km, turn to the right. When you see some white dots, of quartz, there, you will find the Argyroderma delaetii, and the small Oophytum nanum in blossom.

So, with the Hasselblad on one side, and a small pot of water on the other, I had a good time in creating out of season rains, in order to photograph the opening of the capsules.

When moistened, they open in 2-3 minutes, at the most, but for closing, they need some hours.

I have taken a couple of the to Monte-Carlo, for the enjoyment of my daughters, and they have repeated the show. Then, we have scattered, with solemnity, the seeds on a sandy soil, prepared following a well tested recipe of the Jardin Exotique, and, after 5-6 days of patient nebulizations, in order to dissolve the germinative inhibitors which wrap up the seeds (this is one of the last incredible ruses of the pebble plants, to be really sure that the water is sufficient), the first small leaves did appear.

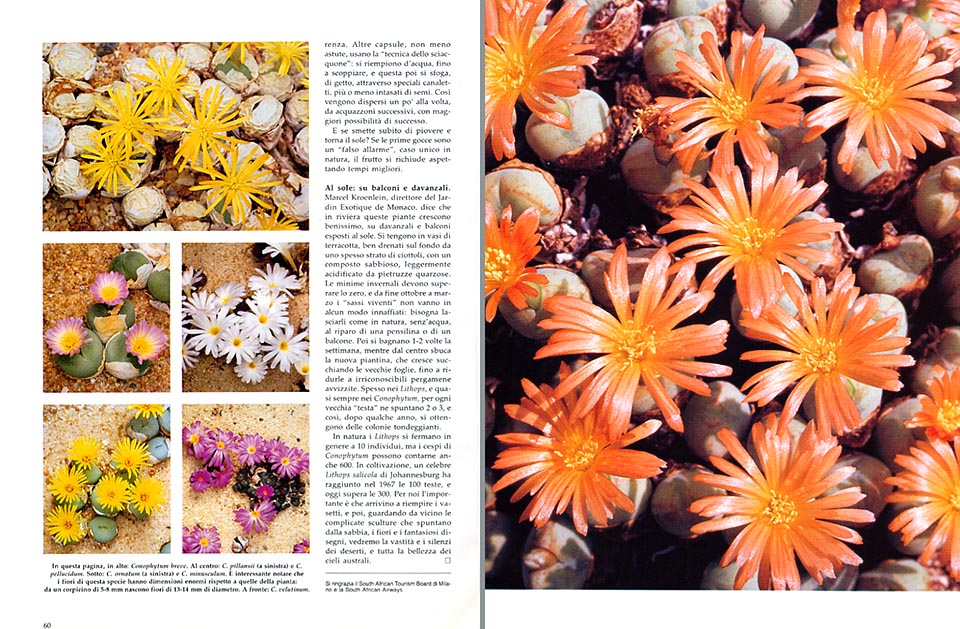

As Marcel Kroenlein, director of the Jardin Exotique de Monaco has confirmed to me, these plants grow up very well in the Riviera, on the window-sills and balconies exposed to the sun.

They must be kept in terracotta pots, well drained, in the bottom by a thick stratum of pebbles, with a sandy compound, slightly acidified by small quartzy stones.

The minimum winter temperatures must always be over the zero, and from the end of October to March, the “living stones” must necer be watered: they must be left as in the wild, without water, at the shelter of a roof, or a balcony.

Then, they must be watered 1-2 times per week, while, from the centre, the new small plant comes out, which grows up sucking the old leaves, reducing them to not recognizable withered parchments.

Often in the Lithops, and almost always in the Conophytum, for each old “head”, there are 2 or 3 coming out, and so, after a few years, you can get some roundish colonies.

In the wild, the Lithops generally stop to 10 individuals, but the tufts of Conophytum can have even 600 of them. When cultivated, where food and water are not missing, a celebrated Lithops salicola of Johannesburg has reached, in 1967, the 100 heads, and now has more than 300 of them. A real record for the Guinness Book of Records!

For us, it is important that they can fill up the small pots, and then, while looking closely at the complicated structures which come out from the sand, the flowers and the fanciful drawings, we shall see the wideness and the silences of the deserts, and all the beauty of the southern skies.

GARDENIA – 1987