Text © DrSc Giuliano Russini – Biologist Zoologist

English translation by Mario Beltramini

Male of Ostrich running at 60-65 km/h © Giuseppe Mazza

The order of the Struthioniforms (Struthioniformes), which included time ago also the cassowary, the nandu and the emu, has only the family of the Struthionids (Struthionidae), seen that nowadays the ornithological biologists have placed the nandu into the order of the Rheiforms (Rheiformi) and the cassowary and the emu into that of the Casuariiforms (Casuariiformes).

All corridor or ratite birds, unfit for flight, not keeled, seen that at thorax level the furcula is missing, the “keel”, which is the junction point of the pectoral muscles and the wing muscles necessary for the flight.

The Ostrich (Struthio camelus), about which here we treat, is bigger as structure than any other extant bird (whether flying or ratite) on the planet. An Arab legend says that it was born from the crossing between a camel and a bird.

Once, the ostriches were very much hunted for providing the women’s fashion industry which required a lot of candid feathers of the wings and the tail of the adult male specimens.

But, starting from the end of the first half of the XX century, due to the evolution of the fashion and to the breeding, such a practice did discontinue and with it also this danger of extinction.

This has allowed the populations of these splendid birds to reinvigorate in their habitats.

Unluckily, after the feathers, it was the turn of the meat and the eggs at alimentary-industrial level, not to forget the leather goods industry.

The consumption of meat and eggs of ostrich was a prerogative of the local tribes in their geographical zone. They were using them with parsimony, just for their nutritional needs, without killing for other reasons, utilizing the feathers for tribal purposes, but when the fashion of consuming meat and eggs came to life also in the western countries, the ostriches, again have risked the collaps of the species.

Luckily, these animals are easy to reproduce, and the growth of breeding farms in South Africa, Europe, Australia and America has saved, at least for the moment, this species in the wild. In any case, IUCN, CITES and Wwf are continuously checking the number of heads in wild state.

Ostriches mating. The male’s neck swells blazing © Giuseppe Mazza

The ostrich was already extinct, by the end of the XIX century, in some geographical areas, such as western India, Persia (Iran), where a particular race might be encountered, and by the beginning of the XX has disappeared also an Arabian autochthonous race, the Struthio camelus syriacus.

The hunting to the ostrich was done essentially by men on horseback, who, once identified the male of the group, with its particularly nice feathers, isolated the animal from the other members and were chasing it till when the poor bird, exhausted by fatigue, was compelled to stop or, however, to be captured by means of a lasso.

It was, and unluckily still is, utilized by some populations as hauling or even as pack animal, as it is very strong. An adult male ostrich is, in fact, capable to run carrying a man on the back, or pulling a cart loaded with goods!

Curiously enough, such employment did not develop in Africa, the origin country, but in south-eastern Asia where this bird was imported.

Presently the ostrich and the four races in which the species subdivides, is found in a vast semi-desert stripe south of Sahara, in part of north-western Africa south of Atlas, from Sudan to Tanzania and to Kenya in eastern Africa, up to the Horn of Africa and in the north-western area of the South African Republic.

The present four subspecies, known to the biologists, are the :

►Southern or South African, Ostrich (Struthio camelus australis Gurney, 1868).

►North African, or Sub-Saharan, Ostrich (Struthio camelus camelus Linnaeus, 1758).

►Masai Ostrich (Struthio camelus massaicus Neumann, 1898).

►Somali Ostrich (Struthio camelus molybdophanes Reichenow, 1883).

The ostriches love the wide spaces typical of the African savannahs and prairies. They are found in abundance also in the deserts, or at least by their edges. In these habitats, they are aided by their speed, which they may maintain even for long distances at 60-65 km/h, and by the excellent eyesight, which they can rotate to 360°, a remarkable radius which allows them to sight the dangers well in time.

They may be found, seldom, also close to the bush, for hiding to the sight of their most dangerous predator, the Lion (Panthera leo), one of the few capable to kill an adult male ostrich, as they are very strong birds, dangerous, courageous and aggressive, which may, with the nail of the foot, cut up the belly of a man or of a hyaena.

The legend, which is represented also in many nice cartoons and comics, after which a frightened ostrich hides the head under the sand, is just a legend and remains as such !

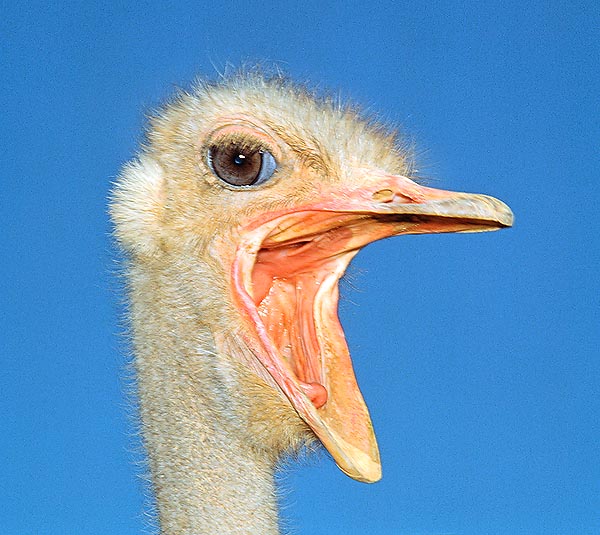

Pliable jaws for opening the wide beak. Omnivorous, the stones help in digesting © Giuseppe Mazza

These huge birds, when very much frightened, may at most run away for hiding into the thicket or bush.

The ostriches have a rather bulky trunk, with ample and convex back.

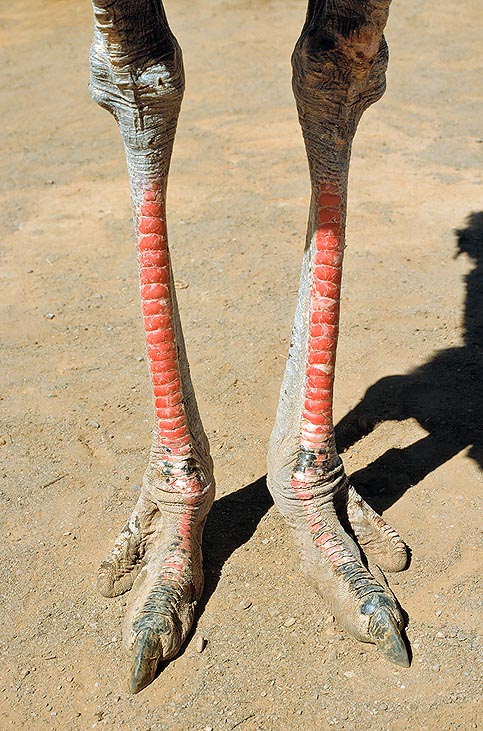

The legs, conversely, are very long and exceptionally robust, with thighs without feathers (only some bristles are present), and equipped with a powerful musculature.

The tarsi are covered by scales.

The foot, only case among the running birds, is provided of only two long and strong toes, which lay and an expanded pad, the inner toe is furnished of a fearful broad nail, flat and cutting like the blade of a razor.

Most of the body weight of the animal lays on this toe.

The neck, very long, is pink in the male and grey in the female, covered by feathers only in the third basal, whilst for the remainder it has only a sparse down, which is observed to be thicker on the head, which is small and flattened on the upper side.

The beak is quite robust and compressed above, with a strictly rounded apex.

The jaws are pliable, which allows the beak to open wide the two branches so much that the upper one almost touches the eyes.

A female defends the nest, simple depression in the soil © Giuseppe Mazza

On the back of the upper branch of the rhamphotheca (beak), are present two ample nares, the eyes are big with big black or burnt brown pupils, whilst the eyelids are furnished with long eyelashes, which protect the eyes from the powder debris and the sand.

The ears are lateral and covered, full of thread-like material. The plumage is long and soft but not too thick, and is practically absent at the centre of the chest.

The feathers of the body in the adult male are black (both primary and secondary coverts), whilst those of the wings and the tail are candid white: the female, on the contrary, has a much more eclipsed plumage, almost uniformly greyish; characters of stable sexual dimorphism.

The hairless part of the neck, besides showing a difference of colouration between male and female, is of different colouration also in relation to the race, varying from the mouse grey to the fawn or the marine-sand beige.

Among all species of the extant running birds, the one more related to the Struthio camelus is the Greater rhea (Rhea americana), South American ratite. The ostrich differs from this one as having only two toes on the feet, instead of three, most of the neck is hairless, and a bigger size.

Furthermore, in the male ostrich, the colouration of the livery is much more variegated than in the ñandu, male as well as female. A male adult ostrich may reach the height of 2,50 m and the weight of 100 kg; the female, the 2,10 m and about 80 kg.

The chicks, upon their birth, are already able to walk (apt-presocial offspring), and are already a forty cm tall.

The ostriches are genuine omnivores. They nourish of berries, rhizomes, tubers, roots, small plants, but also of invertebrates, insects, arthropods and also of small reptilians, even of some micro mammal of the savannah, during the arid seasons, when the vegetation is poor.

Just born, the ostrich is already 40 cm tall and in few days it may run © Giuseppe Mazza

They live more or less crowded groups.

The smallest ones are composed by one only male and a maximum of a dozen of females, the personal harem.

In the most numerous groups, we may count even several males, which are however always considerably less than the females, as it is a species distinctly polygamous.

We have to keep in mind that along with the anatid anseriforms, the ostriches stand among the few birds equipped of a sort of penis, by which they penetrate the vaginal cloaca of the female during the copulation.

The structure of this penile bone has on the back a carved duct through which the seminal liquid glides at the emission, reaching the cloaca of the partner.

Not only, such penis (see Psittaciformes), allows these birds to urinate liquid, thus enabling them to emit pheromones of sexual attraction, towards the chosen partner.

The ostriches do not build real nests, but they merely lay the big eggs in a little deep, but much ample, depression in the ground.

In this sort of shelters are laid the eggs by all the fecundated females of the harem.

There are no cases of hatching parasitism as the females of another harem cannot lay there their own eggs.

As an average, an egg may weigh even 1,5-2 kg !

The ostrich is the only 2-toed bird. The nail is wide, flat and sharp © Giuseppe Mazza

Each female lays, in an interval of time varying from one to three weeks, a number of eggs going for half a dozen to a maximum of twenty.

As this applies for all the fecundated females of a harem, the nest as an average contains a twenty eggs, but in some periods there can be even 80-100 laid eggs!

The hatching, lasting about forty days, is done by the females as well as the male. This last one, who usually is in service during the night, when the predation risks are bigger, usually cares them more than the partners. The eggs are in fact not only to be hatched and protected, but turned periodically with care for getting a perfect incubation.

The chicks, when just born, are about forty centimetres long and are covered by sparse sharp and rigid feathers, almost similar to quills.

Initially the eat the faeces of the parents, and then pass, after a few days, to an omnivorous diet. After a few days, they are able to run quickly, whilst as soon as out from the eggs they are able to walk. The sexual maturity for both sexes is reached only when four, five years old.

It is typical that a male of Struthio camelus, during the mating season, which begins in spring, for attracting the female to the coupling, besides the urination with consequent emission of pheromones, starts a dance of a complexity not inferior to that produced by the males of the Paradise Birds (Paradiseidae). First of all, it places in front of the partner, exhibiting its splendid livery. Then, it opens and closes continuously its majestic wings, and vibrates them of love, bending the trunk and the neck forward, waving it, and goes on in this way till when the female, seduced, cedes.

The ostrich in the wild may live 30-40 years, but in the South African farms, where nowadays is concentrated the 97% of their world population, is much more long-lived and may reach the eighty years.