Interview with Chris McBride, author of a best seller on the protection of South African white lions. In the Zoos of Pretoria and Johannesburg, following the laws of genetics, selective breeding has guaranteed the survival of this species of white felines.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

I am in Melmoth, 70 km north-west of Richards Bay, Natal, and I have in front of me Chris McBride, author of the famous book, The white lions of Timbavati.

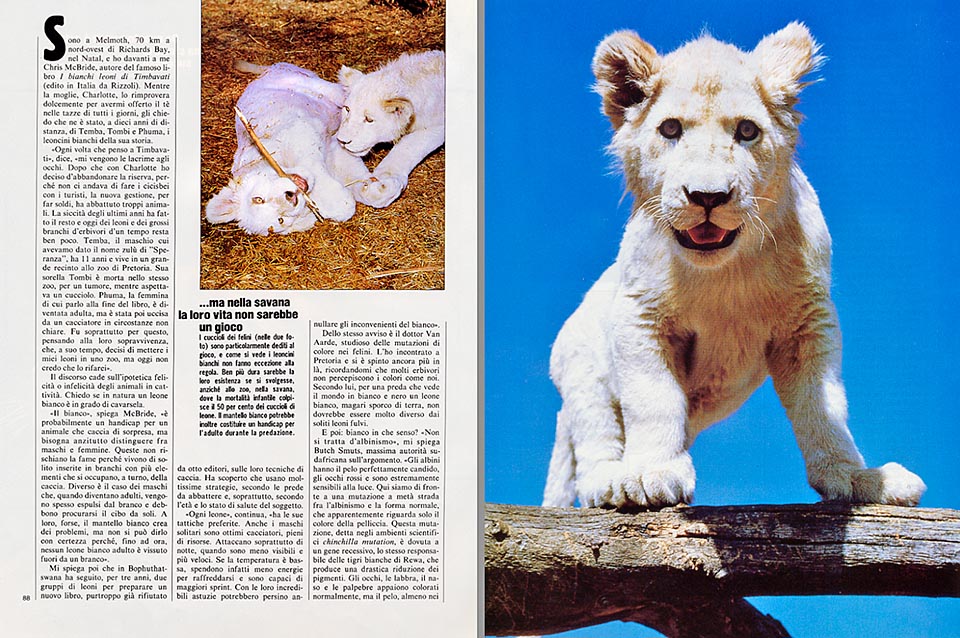

While his wife, Charlotte, sweetly reproaches him for having offered me the tea in all-days cups, I ask him at once what has happened, after ten years, of Temba, Tombi and Phuma, the white lions of his story.

“Every time I think to Timbavati”, he says, “tears come to my eyes. After that with Charlotte, I have decided to leave the reserve, because we did not want to act as cavalier servente with the tourists, the new management, in order to make money, has killed many animals. The drought of the last years has completed the job, and today very few of the lions and of the huge herds of herbivores of the old time are left.

Temba, the male to which we had given the name from the Zulu word “hope”, is 11 years old and lives in a big enclosure in the zoo of Pretoria, and the sister, Tombi, has passed away in the same zoo, due to a cancer, while pregnant. Phuma, the female of which I talk at the end of my book, has grown up, but later on has been killed by a hunter in unclear circumstances.

It was especially for this reason, thinking to their survival, that, at the right moment, I decided to place my lions in a zoo, but today I do not think I would do the same thing again.”

We are talking of the hypothetical happiness of misery of animals in captivity, and I ask him if in nature, leaving on a side the man, a white lion would be able to survive.

“The white colour,” McBride continues, “is probably a handicap for an animal which hunts by surprise, but we have, first of all, to make a distinction between males and females.

The latter don’t risk any hunger, as, normally, they live in herds with several individuals which take care, by turns, of hunting.

The case of males is different, as, when they become adults, they are often expelled from the herd, and must find the food by themselves. For these ones, maybe, the white mantle causes some problems, but we cannot be sure of this, because, till now, none of the adult white lions has lived out of the herd.”

He explains me, than, that in Bophuthatswana he has followed, for three years, two groups of lions to prepare a new book, unluckily already refused by eight editors, about their hunting techniques.

He has discovered that they use many strategies, depending on the preys to catch, and, mainly, on the age and the health status of the subject.

“Each lion”, he goes on, “has its own preferred tactics and even if alone, males are very good hunters, full of resources.

They attack mainly during night time, when they are less visible and faster. If the temperature is low, they spend in fact less energies to cool down and are capable of effecting major sprints. With their incredible tricks, they could even cancel the drawbacks of the white colour.”

Of the same opinion, is Dr. Van Aarde, who studies the colour mutations among the felids. I have met him in Pretoria, and he has gone even further ahead, remembering me, rightly, that many herbivores do not perceive the colours as we do.

After him, for a prey which sees the world in white and black, a white lion, maybe also dirty of soil, should not be much different from usual tawny lions.

He suggests me than to interview Dr. Butch Smuts, the maximum South African authority on the matter, who has just published an article about white lions.

“It’s not matter of albinism,” Butch Smuts tells me, in his office, between a telephone call and another, “albinos have the hair perfectly candid, red eyes and are extremely sensitive to light, but of a mutation half-way between albinism and the normal form, which apparently concerns only the colour of the fur.

This mutation, called in the scientific environment “chinchilla mutation”, is due to a recessive gene, the same which is responsible of white tigers of Rewa, which causes a drastic reduction of pigments.

Eyes, lips, nose, and eyelids, appear normally coloured, but hair, at least in young individuals, is totally white.

Later on, in adults, time passing, it tends to become yellowish or brown-sepia, but a “chinchilla” lion, even if aged, will be always different from a normal lion.”

“Recessive gene”, I interrupt him, ” means that, in order to appear, it must be carried by both parents?”

“Right, and such a coincidence in nature, is, obviously, quite unusual.”

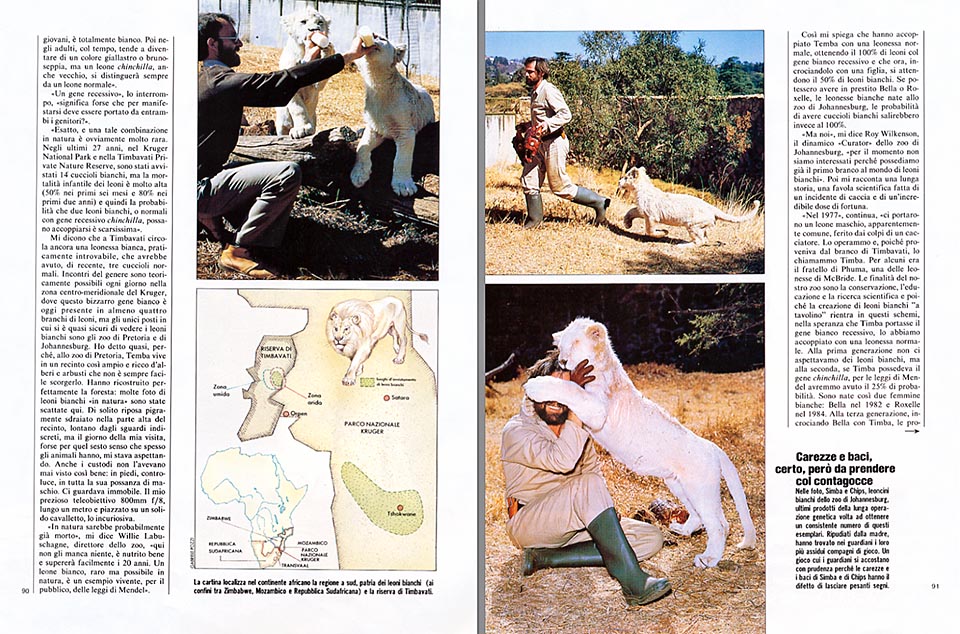

During the last 27 years, 14 white puppies have been sighted in the Kruger National Park and the Timbavati Private Nature Reserve, but the death-rate of young lions is very high (50% in the first six years and 80% in the first two years), and therefore the probability that two while lions, or normal ones, but with the recessive “chinchilla” gene, could mate is very scarce.

They tell me that at Timbavati, there is still a white lioness going around, practically untraceable, which should have had, recently, three normal puppies.

Similar encounters are theoretically possible every day in the central-southern Kruger area, where this odd white gene is nowadays present in at least four herds of lions, but the only places where one can be almost sure to see white lions, are the zoos of Pretoria and Johannesburg.

I said almost, because in the zoo of Pretoria, Temba lives in an enclosure so vast and rich of trees and bushes, that it is not always easy to perceive it. They have perfectly reconstituted the “bush”, and many photos of white lions, “in nature”, have been done here. Usually, it rests lazily, lying down in the upper part of the enclosure, away from indiscreet looks, but on the day of my visit, perhaps for that sixth sense that often animals hold, it was waiting for me.

Also the watchmen had never seen it so well: standing on the border of the “bush”, against the light, in his full virility. It was looking at us, motionless. My precious 800 mm, one metre long, and placed on a solid easel, was rendering it curious or, maybe, it was reminding similar “trifles”, in front of which had been sitting, when young, for the book of McBride.

“In nature it should have already passed away”, says Willie Labuschagne, director of the zoo, “here, nothing is missing, it’s well nourished and will easily live more than 20 years.

Personally, I am contrary to expose monstrosities or circus phenomena, such as the cross breeding of a lion and a tiger, or a two-headed chicken, but if the task of a zoo is to show the various taxonomic realities, a white lion, rare, but possible in nature, is part of its duties.

Furthermore, white lions are a living example, for the audience, of Mendel’s law.”

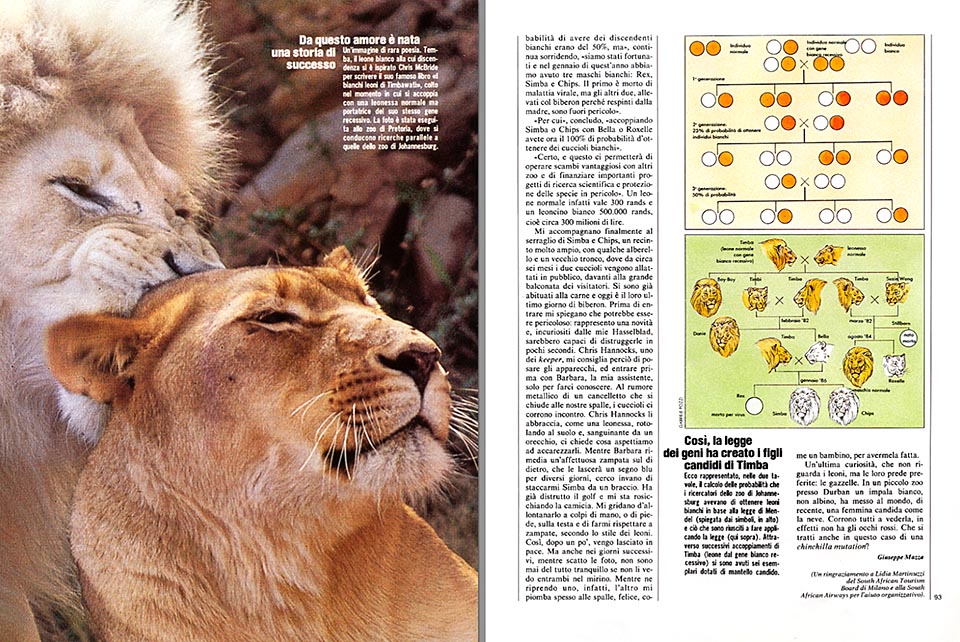

So, he explains to me that they have mated Temba with a normal lioness, getting the 100% of lions with the recessive gene, and that now, cross breeding it with a daughter, they expect the 50% of white lions. If they might borrow Bella or Roxelle, the white lionesses born in the zoo of Johannesburg, the chances of having white puppies would instead increase to 100%.

“But”, Roy Wilkenson, the energetic Curator of the zoo of Johannesburg, tells me, “for the moment, we are not interested in the thing, because we hold already the first herd in the world of white lions.”

He then tells me a long story, a scientific tale composed of a hunting accident and an incredible quantity of luck.

“In 1977”, he goes on, “They took us a male lion, apparently common, injured by the shots of a hunter. We have operated it, and, as it was coming from the herd of Timbavati, we named it Timba. Somebody thought it was the brother of Phuma, one of McBride lionesses.

The finalities of our zoo are the conservation, the education and the scientific research, and since the programmed production of white lions was part of these outlines, we have mated it with a normal lioness, hoping that Timba would bear the white recessive gene.

For the first generation, we were not expecting white lions, but at the second, if Timba held the “chinchilla” gene, for Mendel’s law we would have the 25% of probabilities.

Thus, two white female were born: Bella, in 1982, and Rowelle, in 1984.

At the third generation, cross breeding Bella with Timba, the chances of having white descendants were of the 50%, but”, he goes on, smiling, “we have been very lucky, and in January of this year, we got three white males, Rex, Simba, and Chips.

The first has perished of a viral sickness, but the other two, nursed with a milk bottle, because rejected by their mother, are now out of danger.”

“Therefore”, I conclude, “by mating Simba or Chips with Bella of Roxelle, you have now the 100% of probability to get white puppies…”

“Sure, and this will enable us to operate beneficial exchanges with other zoos, and to finance important projects of scientific research and protection of the species in danger.”

“A normal lion,” adds in fact Denise Woods, the girl of the South African Tourism Board, who has organized my interviews, “is worthy 300 Rands, and a white young lion, 500.000 Rands, that is about 150.000 Euros.”

They take me, finally, to the cage of Simba and Chips, a very spacious enclosure, for two puppies, with some small trees, and an old trunk, where, since about six months, they are nursed in public, in front of the big visitors’ balcony.

They are already accustomed to eat meat, and today is the last day of the milk bottle. Before entering, they tell me it might be dangerous: I am a newness, and, curious for my Hasselblads, they could be able to destroy them in a few seconds.

Chris Hannocks, one of the keepers, suggests me to lay down the cameras, and to enter first with Barbara, my assistant, only to make us known.

At the metallic sound of the small gate closing behind us, the puppies run towards us.

Chris Hannocks embraces them, like a lioness, rolling on the ground, and, bleeding from one ear, asks us what we are waiting for, to caress them. While Barbara gets a blow of a paw on her lower back side, which will leave a blue mark for several days, I try in vain to pull off Simba from my arm. It has already destroyed the sweater and is gnawing my shirt.

They cry to me to pull it off with hand blows, or foot, on the head, and to make myself respected, like lions do, with blows with the paws.

So, after a while, I am left in peace, but also during the following days, when I was shooting photos, I was never completely calm, if I could not see them in the view-finder.

While I was filming one, in fact, the other was rushing upon me, happy for having cheated me.

A last peculiarity, in this subject, which does not concern, this time, the lions, but their preferred prey: the gazelles. In a small zoo near Durban, a white impala, not an albino, has given birth, recently, to a female as candid as the snow. Everybody run to see it, and it does not have red eyes.

Is it also in this case, a “chinchilla mutation”?

NATURA OGGI – 1986