Family : Anatidae

Text © Dr Davide Guadagnini

English translation by Mario Beltramini

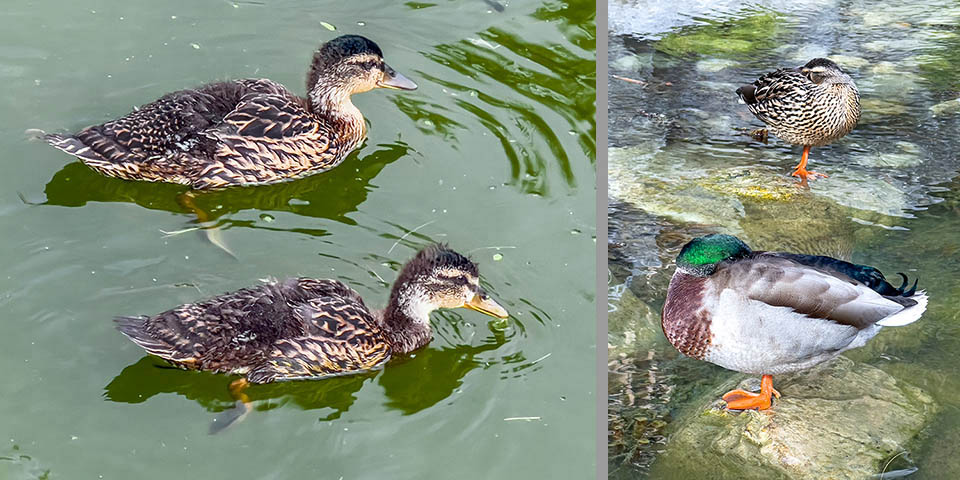

Anas platyrhynchos male in nuptial livery. Draws females attention but predators too © Giuseppe Mazza

The well known Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos Linnaeus 1758) is a bird belonging to the order of the Anseriforms (Anseriformes), family of the Anatids (Anatidae), genus Anas, species Anas platyrhynchos. The ornithologists distinguish today three subspecies: the Anas platyrhynchos platyrhynchos Linnaeus 1758; the Anas platyrhynchos conboschas Christian Ludwing Brehm 1831; and the Anas platyrhynchos diazi Robert Ridgway 1886. A fourth subspecies, the Anas platyrhynchos oustaleti, officially extinct from 1981, lived on the Mariana Islands in the Pacific Ocean.

The name of the genus “anas” is the name the old Romans were giving to the ducks.

The name of the species “platyrhynchos”, comes from the Greek “platys” = broad and “rygcos” = bill, with reference to the bill, decidedly broad and flat of this bird.

Zoogeography

The mallard is the most diffused species of duck (several million of individuals) as wild species and also as domestic as it has originated countless races of domestic ducks. The wild population is present in a very ample belt of the arctic hemisphere (temperate and subtropical regions): North America, Europe and Asia. It has also been introduced in New Zealand and in Australia.

Its migrations extend from the Arctic Circle up to the Tropic of Cancer; in Europe, during the winter, the mallard reaches the North Africa, the Acores, the Canary and Madeira islands; in Asia, the species extends geographically up to India and Myanmar; in America, it lives in the central belt.

The domestic forms of the mallard (Anas platyrhynchos domesticus) are a great many and have been selected for the production of meat, eggs, feather dusters, as beauty and company animals, for keeping clean the paddy fields from aquatic plants and insects, as decoy animals. The first domestic forms have had their origin in Asia; in China the mallard is bred since thousands of years, and have diffused with a huge number of races, forms and variants which have colonized the whole world.

Females have shabbier livery to camouflage while hatching and caring ducklings © Giuseppe Mazza

Ecology-Habitat

It has quite a varied aquatic habitat: water expanses of different sizes and types, calm rivers, canals, swamps, ponds, meadows, irrigated plains from the sea level up to about 2000 m of altitude.

Driven by the frost, in winter, it may reach the estuaries, the brackish lagoons and the marine coasts.

In the wild, the mallard has mainly crepuscular habits, preferring to spend the central hours of the day hidden in wet sheltered locations and with thick vegetation.

At dusk, the flocks merge for reaching the pastures; these are paddy fields, ponds but also meadows or cultivated fields, where it feels comfortable and not menaced; it is, however, very active also during the day.

Usually, they are routine animals as they have their feeding always at the same time. Usually, during the evening flights, the duck fly low and fast. It lifts off easily and immediately from the water as well as from the land, the flight is fast.

The formations in flight organize in compact flock or in line during the migration. It walks well, with a gait only slightly clumsy; it may occasionally perch on trees while looking for sites for the nesting. The northernmost populations tend to hibernate in the central-southern belt of the planet. An increasing number of specimens tend not to migrate any more keeping sedentary.

Such a phenomenon is greater for the populations which have settled in anthropized sites or where, in any case, the human presence has favoured them in some way. This phenomenon is often accompanied by genetic pollution of the species which, where the man is present, gets in touch with the domestic forms or those living in a semi-wild state crossing with these last. It is now very easy to observe urbanized or semi-wild populations which present, inside them, a great variability of colouration and size (which tends to increase); such birds are obviously less suitable for performing migrations.

All this, biologically talking, in the species interest. Strong voice and broad bill © Giuseppe Mazza

Morpho-physiology

The mallard has a stocky and robust body, is about 50-60 cm long and weighs about 700-1500 g.

The wings are rather long, if compared to the body, and pointed but not much wide. The longest feathers are the second and third primary remiges; the second is emarginated on the inner vexillum, the third is emarginated on the outer vexillum and the fourth remige is slightly emarginated on the outer side. The scapular feathers are fairly long and pointed.

The tail is short, round and formed by 18-20 flight feathers; of these, the central ones have a curled shape in the male with nuptial livery (such structure is called commonly curl).

The tarsus of the paws is scutellate (variously sized flat and broad horny scales) in the front and reticulate (small sized horny scales) in the rear and a length of 36-46 mm. The paws are webbed (the membranes are placed between the fingers positioned forward), the big toe is not lobed as in the other species of dabbling ducks. The legs are positioned at about half of the body and have a nice bright orange colour.

The typical and wild form has a general structure of the body rather flat and low with not very long neck; the bill is almost straight and has about the same length of the head; about 40-58 mm long, broad and gradually flattened towards the apex which is round and has a small pointed structure called “nail”. The bill is higher than it is wide at the base and the inner margins of the two rhamphothecae are covered by transversal horny lamellae used for sifting the water and the sludge looking for foods and for their prehension. On the sides of the upper rhamphotheca, proximally, open the nostrils, small and oval.

For what concerns the wedding dress colouration, the male has the head and the distal part of the neck connected to it of an iridescent and metallic intense dark green colour.

In the mating time males are very insistent to to pluck and down the unwilling © Giuseppe Mazza

This green part clearly distinguishes from the rest of the body due to the presence of a collar of white feathers. The chest is of dark brown-brown-bright reddish colour. After the chest, the belly, the sides and the abdomen are grey, finely vermiculated in white-grey. The dorsal part of the livery, after the collar, is grey brownish reddish turning blackish brown with green reflections more or less from after the junction of the wings and joining the black of the rump. The rump and overtail are black with blue reflections; the tail is grey-whitish with the outer rectrices mostly white. The black of the overtail continues in the central flight feathers of the tail to form a triangle ending in the curled feathers thus forming this structure, typical of the males.

The feathers of the wings, primaries, secondaries and coverts, are grey-beige. The secondary feathers of the wings, along with the nearby coverts, at the dorsal level do form the typical speculum of the species which has a main colour metallic blue with violet reflections and, to a lesser extent, green. The speculum has a double border, white externally and black internally (in contact with the changing portion).

The black portion of the covert feathers which, above, overlaps to the coloured part forms a hoods design and below, the terminal black portions of the flight feathers form drawings like the “tip of fountain pen”.

The scapular feathers are finely vermiculated of grey white, and there is a reddish portion which, when the wing is closed, forms a sort of a lateral stripe, in the middle of the vermiculated grey colour, somewhat reminding the colour of the chest.

The axillary feathers and the inferior wing coverts are of cream colour. What has just been described is the so-called “nuptial” livery of the adult male. This species performs, in fact, two annual moultings and by the end of summer the bright liveries utilized by the males for courting and conquer the females is replaced by a decidedly more mimetic plumage that makes the males to look like their females.

Female can lay even 16 eggs hatched 26-28 days and is the only one caring the progeny © Giuseppe Mazza

When losing the feathers of the nuptial dress, the mallards lose also the remiges and the rectrices and, consequently, the capacity of flying. In this period of high vulnerability, it is useful to be inconspicuous.

The female has decidedly modest colours with respect to the male, important for camouflaging during the hatching and the breeding of the ducklings. The basal colour is tawny-brown striated and spotted of dark-blackish brown in a more or less thick way on all the plumage; forethroat and ventral part of the neck are tawny, apex of the head and dorsal parts of the body are more heavily spotted of dark as well as the chest.

An irregular dark line crosses the eye. The wings are similar to those of the male but browner, the speculum is the same for both sexes. The paws are always orange but with a tonality little weaker than the male.

The sexual dimorphism, in this species, is therefore very evident when the male exhibits the nuptial livery. To a minimally trained eye it is however easy to distinguish the males from the females also during the eclipse phase: the males, in fact, in comparison to the females do have a more greyish head and with thinner dark striations, always on the head, the apex is darker with the presence of a sort of wide blackish band, the chest is more reddish and spotted rather than striated of black.

Always different, between the two sexes, is the colour of the bill which s yellow-olive green with black apex (nail) and nostrils in the males (also during the eclipse phase). The bill of the females is on the contrary orange with a more or less ample blackish dorsal portion of the third central of the bill with the presence, or not, of spottings always blackish in the adjacent parts, also in the female the apex (nail) and the nostrils are dark. Also the vocalizations are different in the two sexes: the females are more boisterous and emit some noisy classical “qua, qua, qua”, especially if upset or annoyed, the males emit lower and deeper sounds, such as “quarchh, quech” more “dragged” and less neat.

The subspecies described so far is the nominal Anas platyrhynchos platyrhynchos, which, finally, is the one vastly more widespread.

It plucks for the nest and faces loudly aggressors ready for everything to save pullets © Giuseppe Mazza

The subspecies Anas platyrhynchos conboschas has a paler colouration in respect to the nominal species; it is slightly bigger (about 10% more) with slightly smaller bill. Its range is limited to the southern coast of Greenland.

The subspecies Anas platyrhynchos diazi called also Mexican duck, is by some considered as a separate species. Both sexes have colouration similar to that of the female of the nominal species, but usually it is darker.

It lives in Mexico and in southern USA and is menaced by hunting, by the reduction of the habitat and by diffusion of the nominal mallard with consequent genetic pollution. The females of the Mexican duck tend, in fact, to mate, when they are present, with the colourful mallards preferring these ones to the conspecific males.

Ethology-Reproductive Biology

The mallard nourishes of aquatic plants, algae, seeds and various herbaceous vegetables; but also of insects, annelids, crustaceans and other invertebrates. It nourishes in surface submerging the head and the neck and raising the tail thus giving the body a vertical posture.

The courting begins by late winter but it is not unusual to have depositions already in February-March. The males tend to be much insistent with the females ad it is not unusual to see groups of males running after the females getting to the point of plucking them on the head-neck due to the continuous tentative of copula interrupted by our pretenders. In this species rape cases have been reported and have been also registered cases where some females have been drowned by males who tried to copulate.

The mating takes place in water with the male getting over the female keeping in balance by seizing some feathers of the head-neck of the same with the bill; the female, who supports its weight, during the mating has the body more or less completely submerged with only the head, or little more, out from the water.

Accompanied by mum for 50 days, they grow fast and can reproduce after one year © Giuseppe Mazza

The mallard nests originally in wetlands, on the shores of lakes and banks of streams, in bushy zones, willow groves, grassy islets, reedbeds and prairies in the proximity of locations with water.

The populations living in lakes or in anthropized aquatic sites have developed a certain confidence: cases have been reported of females having nested in courtyards, on moored boats, on balconies, in pots, etc. The nest is mostly placed on the ground but also in cavities of trees, in other species abandoned nests etc., utilizing grasses, leaves and in general vegetal material for its realization. The brood type is formed by 10-12 (6-16) eggs and the nest is padded with down the female tears off from the abdomen.

The down is used by the mother for covering the eggs when she gets away for nourishing. The egg of the mallard has an average size of 57 per 41 mm (52-61 per 38-43 mm), has green-grey colour with smooth and rather translucent shell and weighs about 47-67 g (4 g of the shell). The hatching, which started once the spawning is completed, lasts 27 (26-28) days. The female takes care totally of the hatching and of the breeding of the progeny. The males, at most, keep close during the initial phases of the hatching, mating with other females available.

The colourful colour of the male seems having formed not only as mark of health and of strength for the reproduction but also for distracting the attention of possible predators on itself thus saving the life of the female to whom is entrusted, almost totally, the important task of the perpetuation of the species.

The just born ducklings are able to follow the mother who will take them to the nearest aquatic location where they will be able to find shelter and food. The upper parts of the pullets are brown-dark; the brown is present on the apex of the head, gets on the back of the neck and goes on dorso-laterally along the whole body. The face is yellow, but a brown stripe crossing the eye, and a point, always brown, in correspondence to the auricular zone. Yellow are also some spots on the back and one line of the wing between the remaining brown part. Always yellow are the lower parts of the body.

Just a month after birth the first feathers already appear. Parents can now watch them dozing on one leg © Giuseppe Mazza

At 50 days from birth, the flight feathers have almost grown and the young Mallards train their muscles for their first flight, starting and landing from a body of water © Giuseppe Mazza

The mother, when facing a possible predator menacing the young, stirs visibly shaking its wings and rails against the opponent or cackles loudly moving away with sprawling gait trying to draw the attention on itself in order to save the ducklings. The young, growing, will have a colouration similar to the mother’s one or of the male when eclipsed but duller and less well designed.

With the growth of the feathers, the sexes of the young when observed close, can be distinguished due to a greater presence of black on the apex of the males and for the slight diversity in the shapes of the black drawings and in the tonalities of brown of the chests which will be respectively dotted (and less striated) and more reddish in the males. The mother will stay with the young for about 50 days, during this time they will acquire the necessary maturity for being able to fly and to reach the independence. They will be ready for the reproduction by the year following their birth.

Synonyms

Anas boschas Linnaeus, 1758.

→ To appreciate the biodiversity within ANSERIFORMES click here.