Appearances deceive. Until few centuries ago, these mysterious animals were classified as plants. Sea-anemones, actinias, corals, gorgonias and flowering worms.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

Animals or plants?

At sight, the showy “corollas”, and the “flowery branches”, might lead to think to some vegetables, and, at least till the beginning of 18th century, this was the scientific official position.

Today, we prefer to talk of “Anthozoans”, that is, of “Flower animals”, primordial creatures, often quite different between them, which have in common a body shaped as a “pouch”, with only one opening surrounded by stingy tentacles.

A mouth, which is of use also for expelling the remainders of digestion, and through which pass the sexual products.

Single individuals, like Sea anemones, or organized in colonies, like Madrepores and Corals.

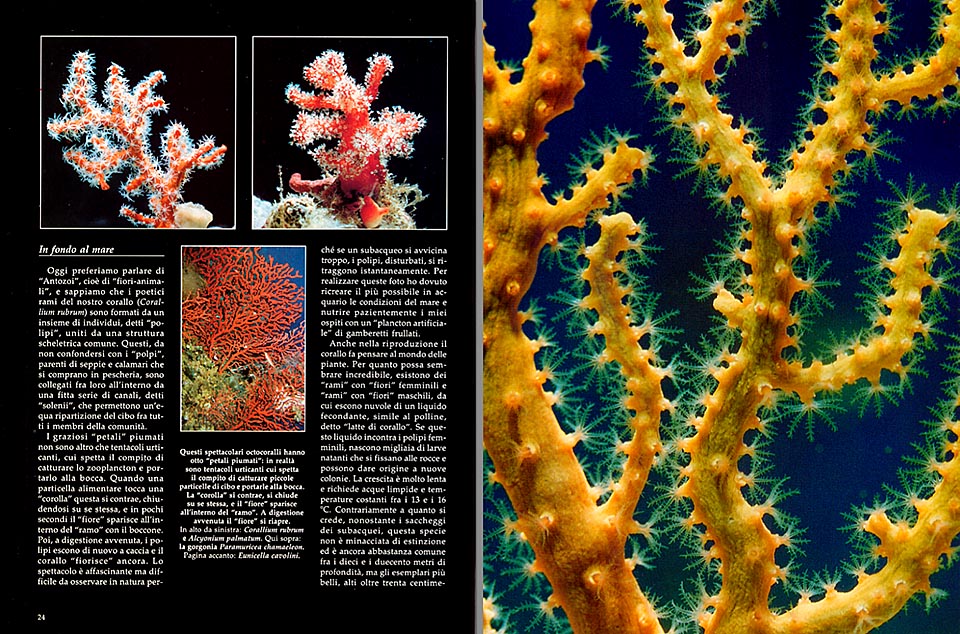

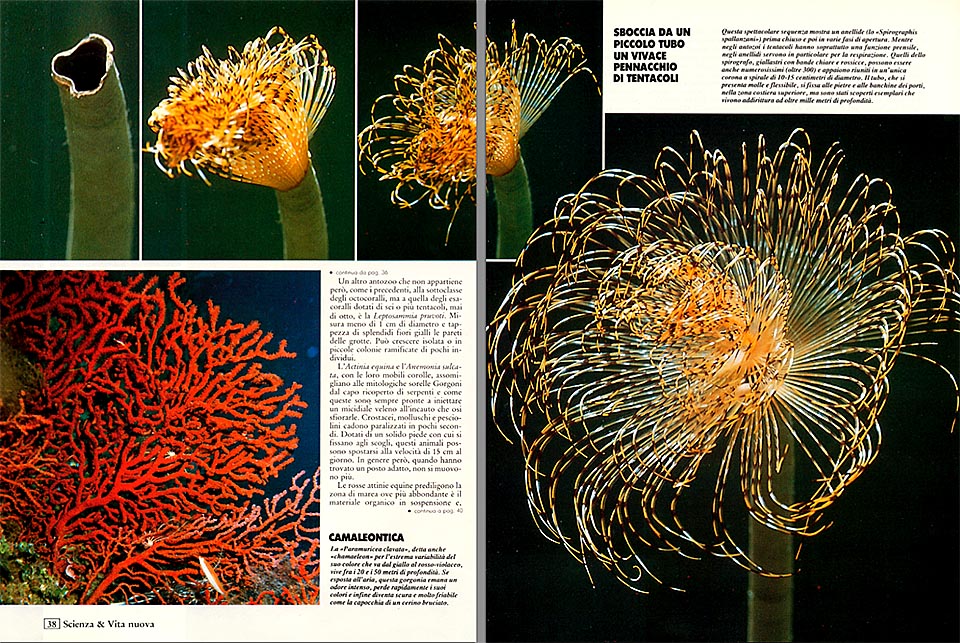

Now we know that the gorgeous branches of the Red Coral (Corallium rubrum), are formed by a whole of individuals, called “polyps”, united by a common skeleton-like structure and connected between them internally by a thick series of channels for the exchange of food between the members of the community.

The small feathered petals, even 1 cm large, are indeed stingy tentacles, which have the charge of catching the zoo plankton : microscopical crustaceans, eggs, small worms, fry, and the nutritive particles in suspension, which wander around carried by the currents.

As they touch the “flower”, this one contracts, and in a few seconds disappears with the bit, inside the “branch”. Then, once the digestion has taken place, they get out for hunting, and the coral is again in bud.

Also the way coral reproduces leads to think to plants. There are female branches and male ones, and from the flowers come out, like pollen, clouds of a fertilizing liquid, called “Coral milk”.

When this meets female polyps, thousands of floating larvae come to birth, and when settling down on the rocks, they will generate new colonies.

A species belonging exclusively to us, the Corallium rubrum, which lives only in the Mediterranean.

It grows only of 3-4 mm. per year, head down, on the deep sea rocks, or on the ceiling of submerged grottoes, between 10 and 200 metres of depth, where there is scarce light, waters are clear and temperatures constantly between 13 and 16°C.

It is not a species in danger. On the depths of Portofino promontory, you can count till 1000 colonies per square metre, but nicest specimen, with ramifications of 30-40 cm., are only a remembrance of the past, and to reform them 100 years will be needed.

To the same group of Octocorallia, the Anthozoans with eight arms polyps, do belong also the Gorgonians (Paramuricea clavata), with fan structures which can be bigger than a metre.

Unlike coral, they develop on only one layer, perpendicular to currents. At 20 metres of depth, where vertical currents prevail, they are almost parallel to the surface, whilst at 30 metres of depth, where the movement of the water is horizontal, they stand straight towards the sky.

True nets for plankton, the seize all what passes by, for the good and the bad; because sometimes larvae of sponges, shells and parasites are hidden inside it, causing then the death of the colony.

At sight, in the bottom of the sea, the branch seems blue: but the light of a torch is sufficient to disclose to divers lively carmine colours with violet gradation, or even yellow, or two coloured.

I has been noted that the populations of centre and north Italy are mainly red, whilst southwards, the tops of the branches become progressively yellow, and at the entrance of Messina straits, only lemon-yellow or orange-yellow colonies are growing.

Even if there have been seen red specimen with white polyps, unlike coral, these have the same colour as the branches. They measure 5-6 mm. Less numerous at the basis, and thick on the summit of ramifications, which, as scientific name suggests, assume the appearance of small clubs. But, above all, the whole structure is more elastic, and therefore, is not suited for being worked.

The calcareous skeletal elements, called “sclerites”, in fact, are not blended together like the coral, but disposed, like pimples, around the dens of the polyps, which go and come from a common fleshy structure, sustained by a brownish horny skeleton which gets black when in contact with air.

In the Hand of St. Peter (Alcyonium palmatum), the sclerites are, on the contrary, scattered in a expansible structure, fleshy and stubby, with conformations similar to the fingers of a hand.

It grows at a depth between 20 and 200 metres, in cold waters, where the current is stronger, settling down on the rocks or on sandy sediments, with a large foot. In the first case, the colony is red, pink or dirty-yellow, in the second case, it’s almost whitish.

It can reach 30-40 cm., and also here polyps show eight small tentacles. As usual, they catch the plankton, taking it inside the colony, but, thanks to special “pump polyps”, the community swells and deflates of water several times a day, doubling or triplicating in volume.

An impressive proceeding, parallel to normal in-out of polyps, with respiratory and nourishing functions.

For a diver, the sight of these colonies, often gathered together by dozens in a limited area, with the white polyps stretched out in the deep blue twilight of the sea, is really an unforgettable view, like a magic submarine blooming. Whilst the polyps are shrunk, they are unlikely seen on the bottom.

The proceeding can be observed well only in an aquarium.

At the beginning, the colony, wrinkled, with its pimply surface, extends, and the outline of the body takes visibly shape.

In transparency, if the light is good, it is sometimes possible to distinguish the calcareous needles which remind the skeleton of a hand seen through X-rays. Then, only when the colony is enlarged at the highest degree, the dots of the polyps opening with their feathered tentacles do appear. Due to the depth where this strange anthozoan lives, it is caught by the trailing nets.

And once, when it was discovered among the fishes, it was scaring, and in fact in various regions it is still called “Hand of the dead man”, or “Hand of the hanged man”. And, seen its alleged magic powers, men were convinced that, grilled, it was curing ll-fated people from thyroid goitre.

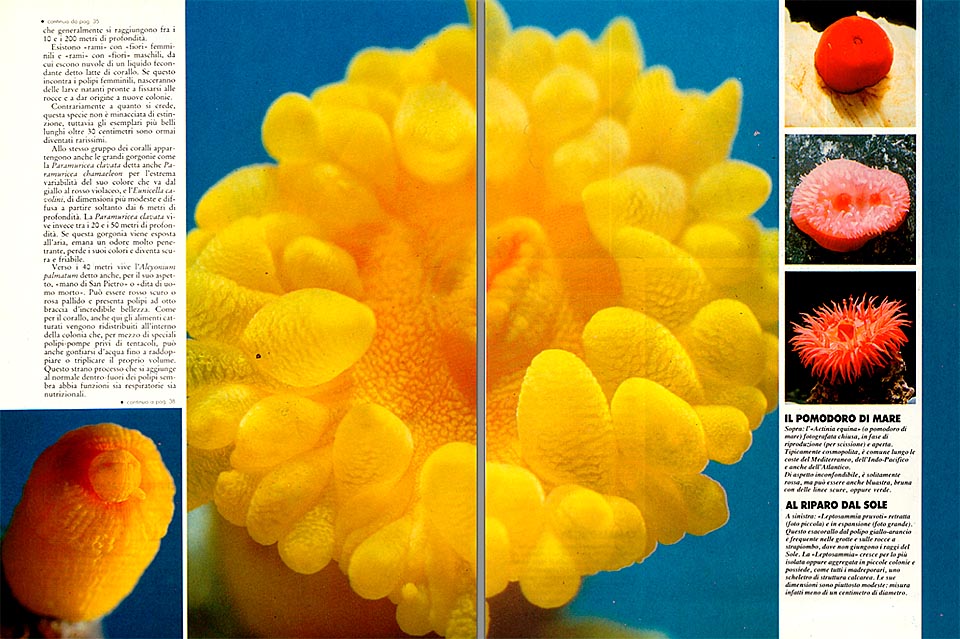

Anthozoans with six or multiple by six tentacles, belong to the group of the Hexacorallia. Colonial individuals, or large sized singles, like our Sea tomato (Actinia equina), or Sea anemones (Anemonia viridis), which number even 380 of them.

With a blazing red, but sometimes also green or brown, the Actinia equina lives idly anchored on the reefs. It can move, at the speed of 15 cm. a day, to reach better fish areas, in the strategic points of the surf and the passage of currents, but then, if she is well located, will not move for weeks.

During the day, or when comes to the surface with the low tide, it assumes, drawing back the tentacles, an almost spherical form. Indeed, we could say a small tomato, born nobody knows how on the rocks, but the smell of a fragment of fish or of a shrimp is sufficient to have the tentacles coming out in the open air, and the unusual fruit, 3 to 5 cm. wide, becomes a showy flower, even double in size.

It is slightly stinging for man, but taking it off carefully, by the foot, it can be transferred in a small marine aquarium, where it will live for years.

Being born to cook under the sun in the puddles of the reefs, it tolerates very well the temperature changes and the rather high temperatures of the dwellings. Does not need great care. A 30 cm. pool with a small filter under the sand and an aerator are sufficient. The water can be collected at sea, or prepared at home with the powders, and it is sufficient to restore the level, as soon as the water evaporates.

In nature, Sea tomatoes catch also small fishes, which they paralyse with their stinging darts; at home, a fragment of shrimp, once a week, will be quite o.k. As soon as it touches a tentacle, in a few seconds, all others will converge towards the prey, which is forcefully pushed to the centre of the flower, which opens monstrously, like a mouth. And, well fed, it can happen frequently that your guest multiplies by two.. a true cloning which renders it theoretically immortal.

But at sea, with several exceptions, sexual generation in the world of Actinia, is the rule. Males emit from the mouth and the tentacles clouds of spermatozoa. The females swallow them, and the fecundation takes place inside the maternal pouch.

We can almost talk of “care of the offspring”, because the young are not exposed to danger, but are expelled after long time, already autonomous, when they have formed a small crown of 12 tentacles, and, sufficiently great, they are strong enough for the big battle of the life.

Sea anemones (Anemonia viridis), differ from Actinias as they cannot retract the stingy tentacles, long even 20 cm and regularly placed around the mouth, on six concentric rows. An uneasy effect, which has justified, for these Anthozoans, also the popular name, very clear, of Hairs of serpent.

They have a mobile foot, wide up to 30 cm, and they settle down on the reefs in shallow waters, never under 25 metres of depth, because their showy moving arms shelter, inside, microscopic symbiotic algae, the Zooxanthellae, which, like all plants, need some light to live.

Depending on their nature and concentration, Sea anemones, look, therefore, pallid grey or green, with the top of tentacles often crimson or violet. It is not well known what is the use of this strange association born million of years ago at the beginning of life; it seems that algae profit of the carbonic gasses emitted by the animal, and that this one gets advantages from the oxygen and the mineral synthesis produced by these very simple plants.

Like Actinias, also Anemones can reproduce by scission, but their poison is very much stronger: it paralyses molluscs instantly, also crustaceans and rather big fishes, and can be dangerous also for the divers who enter without protection in their huge formations.

An antidote, in fact, does not exist, and the reaction, in any case painful and burning, is personal and unforeseeable, not to talk about anaphylactic risks. The one who has been hit, even if feebly, in the past, can in fact suffer from violent cramps, paralysis, and serious breathing problems, easily lethal for the one who is still plunging.

Like for jelly-fishes, it is necessary to rinse immediately with sea water the part affected, to remove eventual stingy filaments still present, and in more serious cases the help of a physician might be required.

While waiting, ammonia compresses may help to struggle against the poison, or half onion, followed by a slice of tomato, which will refresh and hydrate the skin.

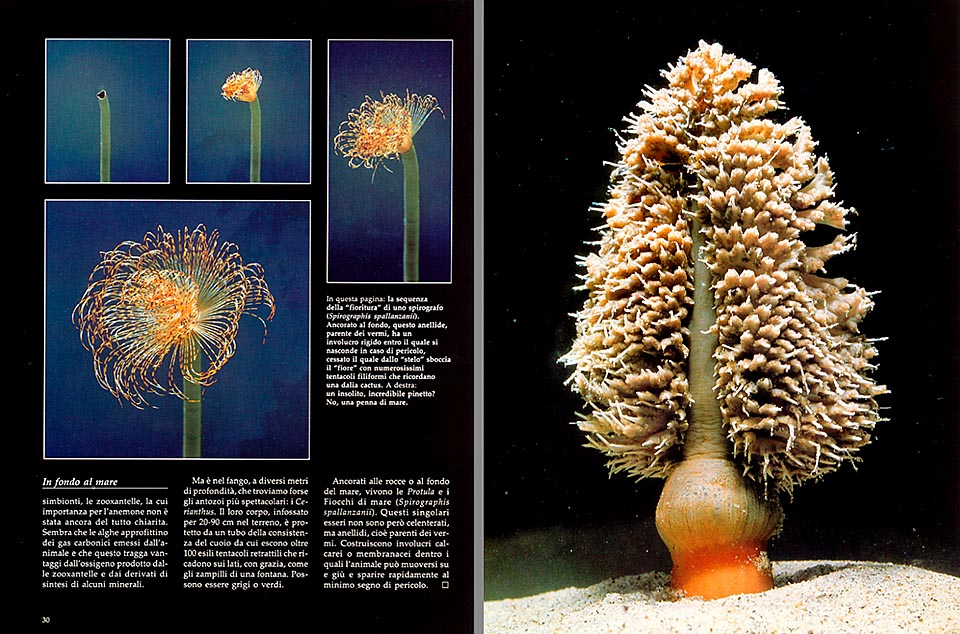

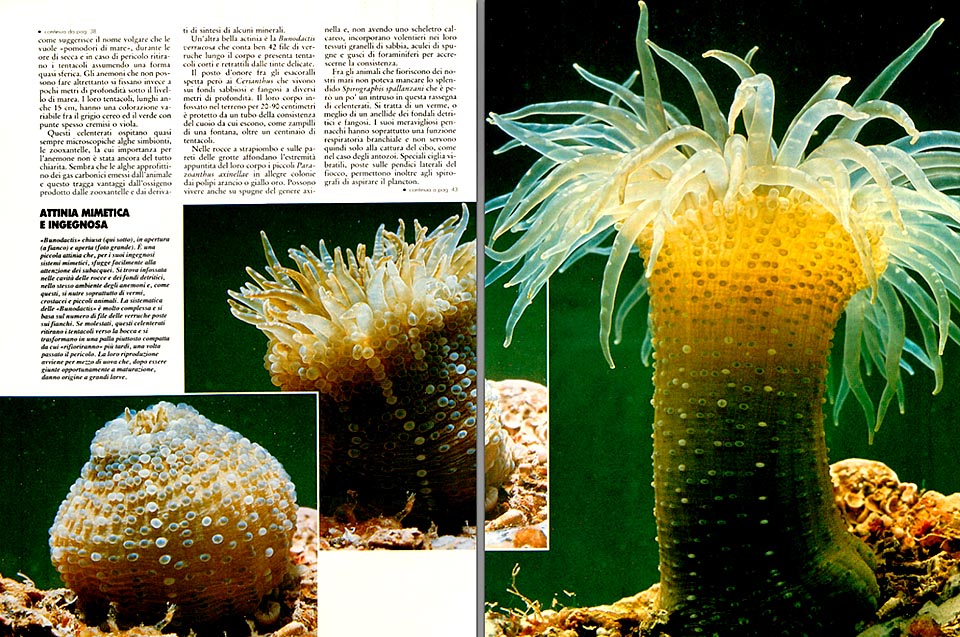

But, it’s in the mud, up to 40 metres of depth, that we find the most imposing Anthozoans: the Cerianthus.

Their body, buried for 20-90 cm., is protected by a pipe as consistent as leather, from which comes out a hundred of retractile tentacles, which slip on the sides, gracefully, as spouts of a fountain.

They can be grey or green, and in a specimen wide only 2 cm., they cover a circle with more than half a metre of diameter.

In the same way, anchored to the rocks or the bottom, live the Protula et the Sea flakes (Sabella spallanzanii), odd beings, with a pyrotechnic appearance, which, however, do not belong to the world of Anthozoans, but to that, much more developed, of the Anellids.

Close relatives to worms, they belong to the group of the Polychaetes. Only in the Mediterranean, we count more than 800 species, often much different between them for shape, colour and alimentary or reproductions strategies.

Some are hermaphrodite, but usually sexes are separated, and also here are those who can manage without a partner and reproduce by themselves by cloning.

Taken off the two extremities, the body, cylindrical, is formed by various segments, all alike, with lateral bristles. The head carries other appendixes with different shape and functions, for catching the food and receiving the surrounding stimuli.

Some of them feed upon debris, others are predators, with mouths furnished of hooks and chitinous teeth.

Those who are inside, pipes fixed on the basis, do live on suspended particles with a filtering fan-like apparatus placed close to the mouth. They build calcareous or membranous individuals, where the animal runs up and down, disappearing after the smallest sign of danger.

But even if holding vibrating brows to move water and filter plankton, their vaporous crests are branchiae, and therefore are mainly of use for breathing.

The Protula, with a double 5 cm. crown, white with small red or yellow-reddish dots, looks like an Olympic flame, and when it draws back in the pipe, puts a cover on it, like some shells, to close completely the door to the world.

We find it, identical, always in good shape, just under the surface of the tides, or at 900 metres of depth, in the absolute darkness.

The reproduction and installation of larvae happen during summer time, when fully developed individuals exhibit their red eggs, enveloped in a gelatinous capsule, all round the opening of the pipe.

The Sabella spallanzanii, bigger, does not go down beyond 60 metres. Its body holds even 300 rings, and from the flexible pipe, long even 30 cm., a 20-30 cm. diameter corolla can get out in a few seconds.

It is formed of two spiral gill lobes, alike when young, which later on differ. The bigger one, displays, like a peacock, long yellow-brownish feathery filaments with white, violet and gold-yellow stripes. When it’s expanded, the brows of the lateral appendixes vibrate continuously, and cause a flow which catches all alimentary particles in suspension, which, glued together by a sort of mucus, elegantly go to the mouth.

Many marine animals are epibionts, that is, adapt themselves to live over other living beings for lack of room. It may seem incredible, but even on the bottom of the sea, competition is rough, and it is not always easy to find an accommodation.

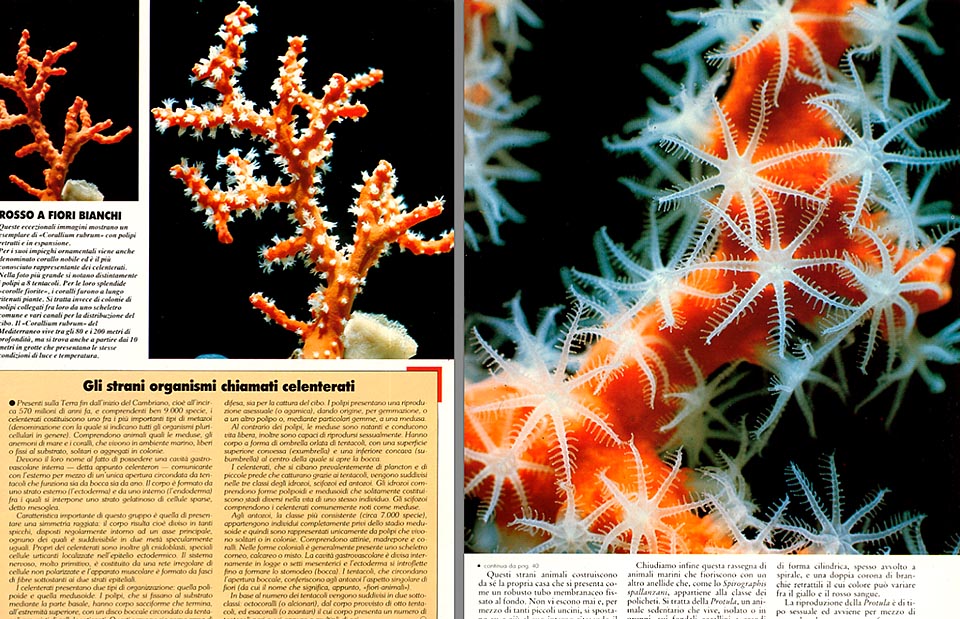

This is the case of the Sea daisy (Parazoanthus axinellae), which grows in the shady side of surface reefs, and deeper, in the darkness, till 240 metres of depth.

When the place wanted is occupied by a sponge of the gender Axinella, it does not hesitate, and settles down over it with its fleshy yellow-orange polyps, which well amalgamate with the tissues of the host. Tall up to 2 cm., they hold about thirty thin tentacles, and appear assembled at the basis in rather wide colonies, very close to each other.

Polyps cannot develop a calcareous skeleton, and in order to replace this gap, while growing, they assimilate in their tissues what they find around: aculei of sponges, small grains of sand, shells of foraminifers and small debris. Everything is good, they must just be firm, in the first row, ready to collect the plankton which comes towards them, dancing with the currents.

Sea daisies belong to the group of Zoantharia, anthozoians spread out mainly in warm seas with about 300 species.

Externally, they often look like small actianiae, but unlike these ones, these do not have a flattened, ring-shaped foot, and cannot move. When young, they thrust the lower sharp extremity in the ground or in the host, which can also be a Tunicate of the gender Microcosmus, and they will not move any more.

Also the Leptosammia pruvoti makes its small underwater show. Animal not wider than on cm. and high two, which graciously overflows from the shell to exhibit an inviting fleshy yellow-orange corolla. It belongs to the group of the lonely corals: and we often find it close to coral, in the grottoes, or on the shady rocky cliffs between 1 and 50 metres of depth. But, unlikely this last, which has a solid internal skeleton, it shelters when resting in an external calcareous skeleton.

In general, it does not live in numerous groups, but, sometimes, pushed by currents, young larvae fix one close to the other on the ceiling of a grotto, which, when illuminated by a torch, becomes and incredible starry sky.

As we have seen in these pages, for the most part, Anthozoans have live colours; but there are species which do their best to be unobserved.

So, in the vast group of Actiniaria, close to the boasting Sea tomato, we find the Bunodactis verrucosa, spread out but rather uncommon, all over the Mediterranean and part of the Atlantic.

Its brown-greenish dress surely is not too showy; and its tentacles, of the same colour, with the outline shattered by mimetic small dots, we could say that they are doing their best not to show the contour; but, not yet happy, this discreet Anthozoian has adorned the outer part of the trunk with innumerable sticky tubercles. And this explains the Latin name of verrucosa.

These ones retain small grains of sand, small fragments of shells, and all what falls by with an astonishing mimetic result between the reefs and the debris bottom.

Divers, attentive and lucky, will note at the most the crown of tentacles, whilst the films done in aquarium, make well evident the shape of the body, more cylindrical of the Sea tomato, when expanding, and the warts absolutely necessary for the identification of the species.

Yes, because the are two kind of discreet and unassuming Actinia: this one with 6 longitudinal regular series of whitish protuberances and 42 rows of warts, and the Bunodactis rubripunctata, which has, on the contrary, 48 rows of more or less sharp warts.

The White Gorgonia (Eunicella singularis), belong to the group of Sea fans. Known also as Eunicella stricta, it’s very common all over the Mediterranean, between 10 and 30 metres of depth.

Its white small branches, tall no more than 70 cm, grow against the currents, like a fan, all at the same level, and seen that the colonies set up mostly parallel on flat rocks, we have at first sight, the impression of being in front of artificial plantations.

The polyps, very small even when expanded, are often unnoticed. White-brownish on surface waters, and greenish down below, due to the presence, like Anelona, of microscopic simbiontic algae.

The simplicity and elegance of the structure, with straight ramifications, often like a chandelier, do impress, but, above all, it’s the “plant of baptism” of divers, the one of the first immersion in the sea with the instructor, in waters rather low and clear, easily accessible.

In addition, it has all the requirements to become a souvenir; because, unlikely other Gorgonia, which turn black or crumble away when exposed to air, it keeps unimpaired, when dried up, its candid rind.

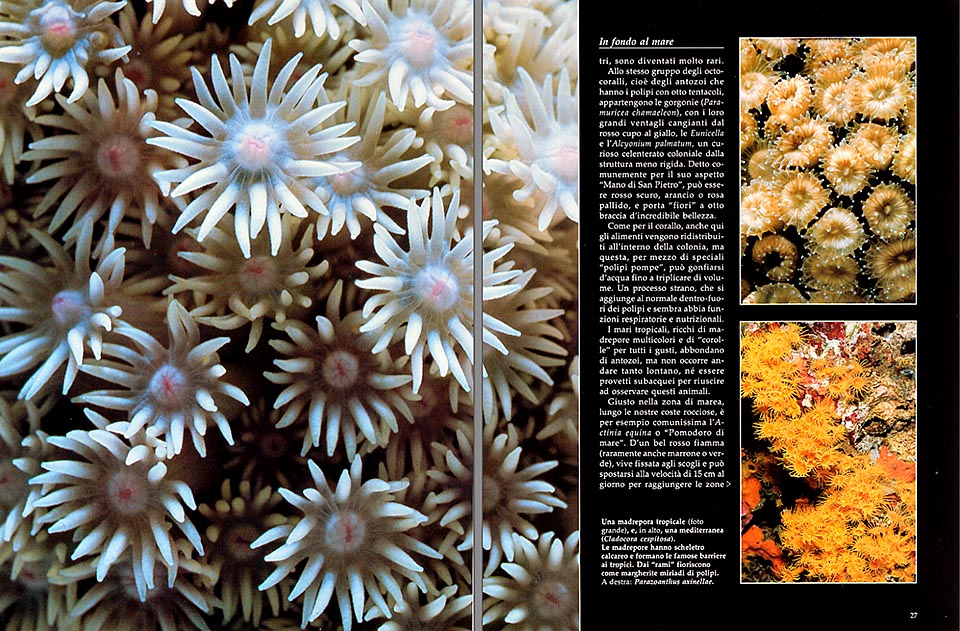

The Madrepore belong, like Actinia and Sea anemones to the group of Hexacorallia, but unlikely these ones, they build up calcareous skeleton, which give shelter to polyps.

When living in crowded colonies, as it happens in tropical areas, by dint of fixing calcium carbonate in their underwater fortresses. They build up, slowly slowly, during millennia, the “reefs”, the atolls, and finally, true and proper islands.

Some species are hermaphrodite, others do have separate sexes. Larvae develop, like Sea tomato, in the maternal pouch and are expelled floating , they move at the speed of 14 cm. per minute, like many small jelly-fishes.

The anatomical difference, after all, is not big, because if you look well, the jelly-fish is nothing else that a reversed polyp. They wander for 1 to 8 weeks looking for a suitable place, and then, with a pirouette, they fix, head down, on the bottom for their final sedentary life.

In parallel lines, many species reproduce in great measure by gemmae, with the young which spring up by thousands like mushrooms, from the inner part of the tentacles.

2500 species with various survival techniques. There is not to be surprised therefore, that, in spite of low temperatures and absence of light, some have colonized also the Mediterranean.

In our areas coralline formations are rather modest, but there are various coastal forms, located between 30 and 100 metres of depth, and abyssal species which reach also 2500 metres below.

They all feed with plankton. Generally, they are closed during the day, open in the night: transparent polyps, green, yellow and red, isolated like a star, or assembled together in ramified colonies, like the Dendrophyllia ramea, or in small cushions, like the Cladocora cespitosa, and the Astroides calycularis.

This spectacular yellow-orange madrepora, is already a warm water species, and in fact can be found only in the southern side of the Mediterranean, on the shady cliffs or in the grottoes.

Sea feathers include more than 300 species, which call to mind the Christmas trees.

The most primitive Octocorallia belong to the order of Pennatulacea. Their colonies are not fixed to a basis, but to a soft bottom, and they move around periodically, just like the Hand of St. Peter.

The skeleton is a simple horny stylus limited to the third inferior of the body, and they distinguish themselves clearly into two parts: a bare stem, and the “feather”, covered with small polyps, disposed singly or in small tufts.

You can count even 40.000 of them on an individual like our Pteroides griseum, which varies between 10 and 30 cm., depending on the swelling.

All the Pennatulacea do have separated sexes. Male and female colonies exist, generally, the last ones are more numerous.

Swimming larvae make pirouettes, fix on the ground, and build

in short time a cylindrical polyp, the basis of which becomes the peduncle.

Then, on the sides , a great number of minor polyps blossoms, which generally replace the main one in the alimentary function, and they are immediately very busty in absorbing and expelling water.

Some species, like the Phosphoric pennatula (Pennatula phosphorea), emit, during night time, a strong blue light. They secrete a mucus which gets alight after tactile or maybe chemical stimuli. Starting from the stimulated point, the colony progressively enlightens, and then it’s really Christmas also in the bottom of the sea.

GARDENIA + SCIENZA & VITA NUOVA – 1984