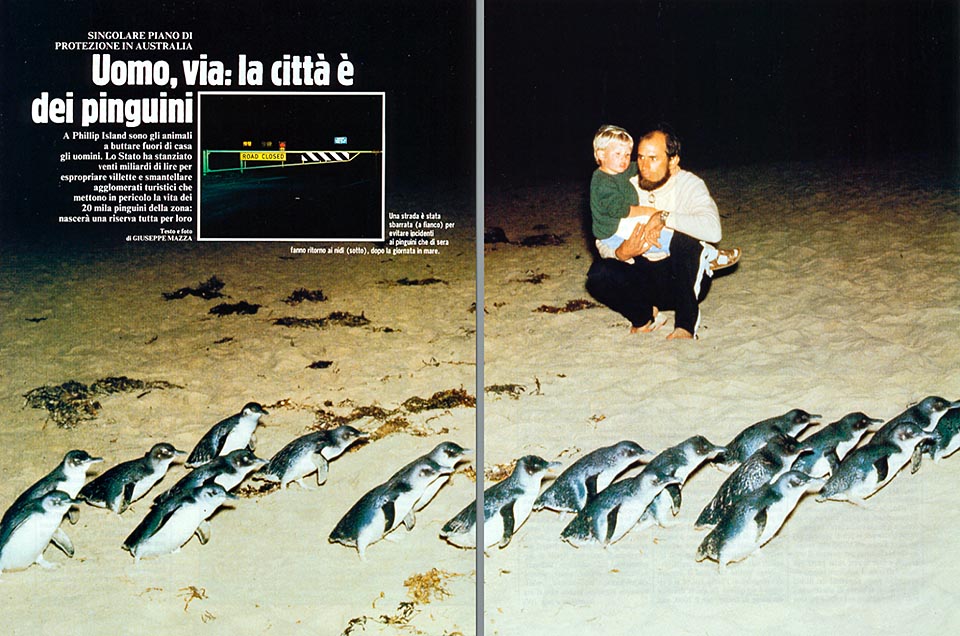

Singular protection plan in Australia : Man out, the town belongs to the penguins. On Philip Island it is penguins that throw men out of their homes. The government allocated 12 million euros to expropriate cottages and dismantle tourist agglomerations that threaten the life of 20.000 penguins in the area. Every night the small penguin goes on parade. The night parade of the penguins that return to their nests under the floodlights for the joy of the tourists. They are the smallest in the world. After fishing in the high sea, they bring food to their chicks waiting in the dunes.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

He who owns a country cottage at Summerland, Australia, will be obliged to sell it to the State of Victoria within 2000, owing to the “fault” of the penguins.

There are still 14 years to go, but Peter Dann, the biologist of the Reserve of Phillip Island, about 100 Km. south of Malbourne, tells me, smiling, that “all hasten to do it”.

He stops the jeep and illuminates a check-point.

“Do you see that house behind the bar? There, after the notice, with lighted windows. It will be abandoned during the next days. Since when they have closed, from sunset to daybreak, the five ways of access to Summerland, people lives like besieged, and think only to pack up”.

“It’s matter mainly of second homes”, he says, “belonging to tourists who come from Melbourne to spend the seek-end and practice the surf-board in the most beautiful side of the island. Locals, once, lived peacefully, respectful of penguins’ rights, till the point of accepting their nests in the cellars, the ceilings, and even under the beds, but later, problems started, with the boom of tourism.

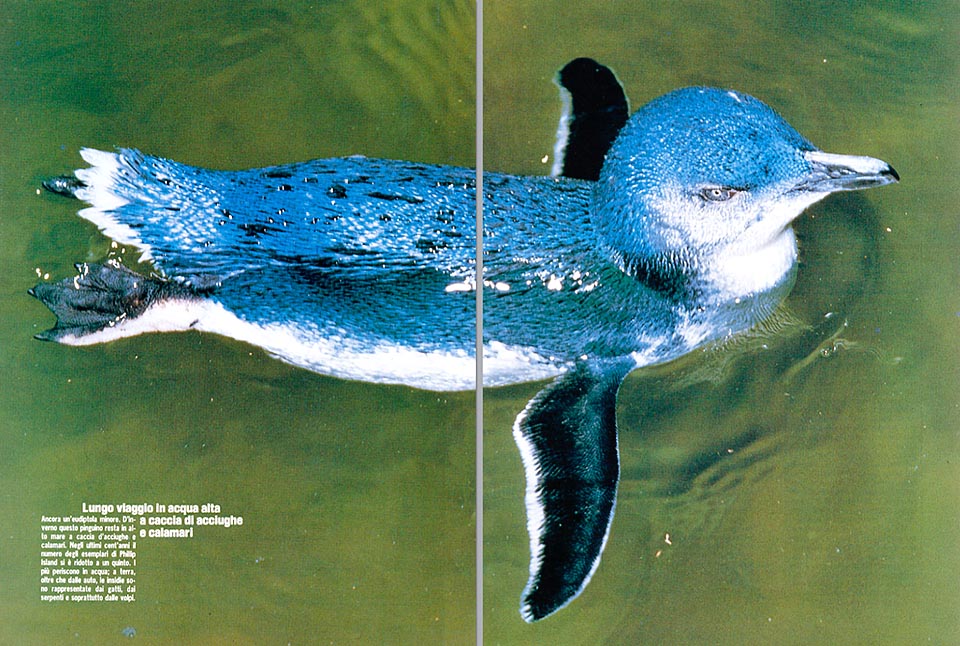

The Fairy Penguins (Eudyptula minor), as Australians call them, spend all their day in open sea, and come ashore only after the sunset, when the darkness come, to breed and feed the young.

Dangling, between many indecisions, they cross the roads to reach their nests, and, blinded by the lights of the cars, they come, regularly, into collisions with hurried tourists. The partner, who is not informed of its widowhood, waits in the nest for 10-15 days, risking to die of hunger, but even if the young come to life, he cannot leave them alone, and in any case, will not be able to feed them.

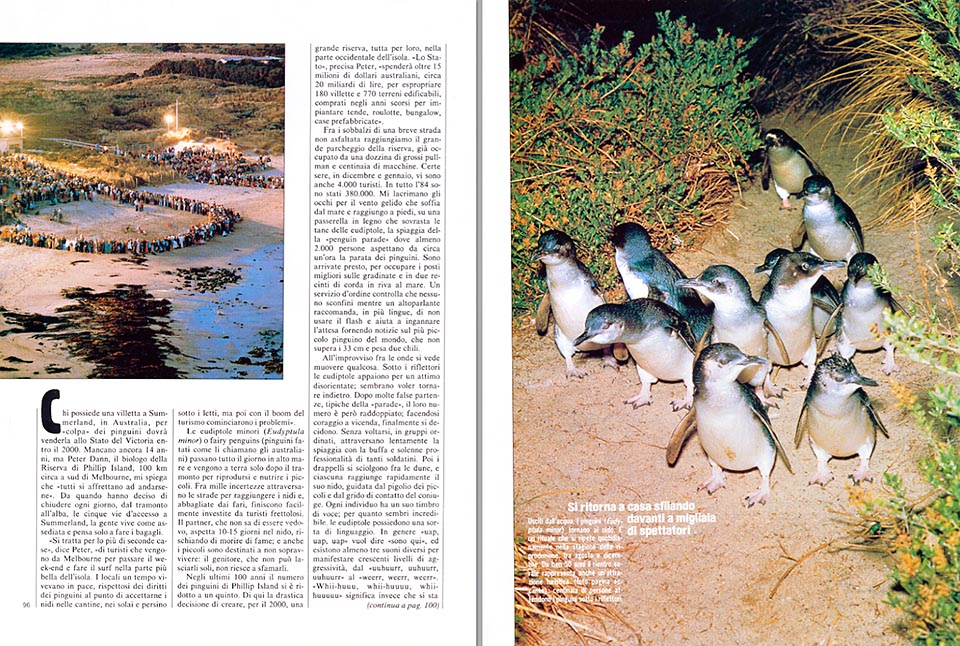

During the last 100 years, the number of penguins of Phillip Island has reduced to one fifth. Since, the drastic decision to create, for the year 2000, a great reserve, all for them, in the western part of the island”.

“The State”, Peter continues, “will spend more than 15 millions of Australian dollars, about 20 billions of Liras, to expropriate 180 country cottages, and 770 building areas, purchased during the last years to install tents, motor-homes, bungalows, and pre fabricated houses.”

After the jumps of a short, not asphalted road, we reach the large parking place of the reserve, already occupied by a dozen of buses and hundreds of cars. During some evenings, in December and January, there are here even 4.000 tourists. 380.000 for the whole 1984.

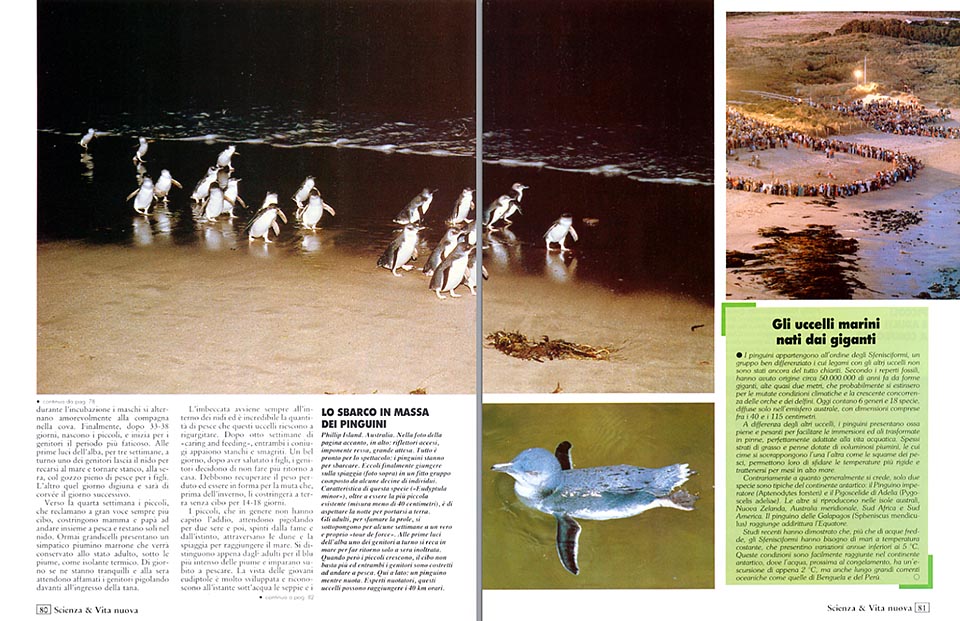

I have tears in my eyes, due to the icy wind which blows from the sea, and I reach, by walking, on a wooden footbridge which stands above the den of the Fairy Penguins, the beach of the “Penguin Parade”, where 2.000 persons at least, are awaiting, since about one hour, with the risk of rain, the “Penguins’ Parade”. They have come early, with wind jackets, thermos, and blankets, to have the best seats on the staircases and in two enclosures surrounded by ropes on the seashore.

A rigid service for the maintenance of order controls that nobody trespasses, while a loudspeaker recommends, in various languages, not to use flash lights, and, whiles away the time with news about the smallest penguin in the world, which measures no more than 33 cm, and weighs a maximum of 2 Kg.

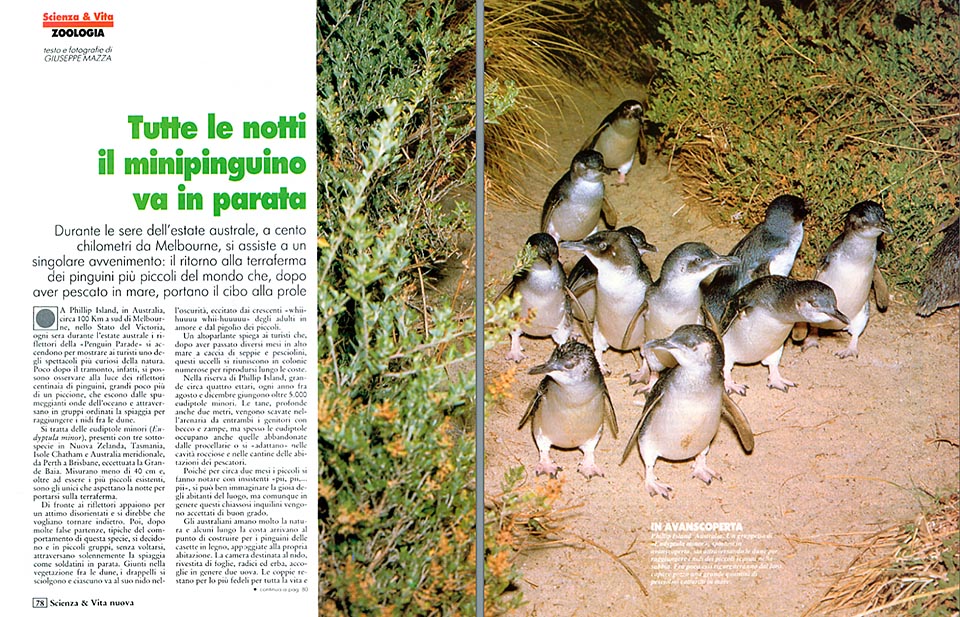

Suddenly, we can see something moving between the waves. Under the searchlights, the Fairy Penguins look, for a moment, confused, and seem wanting to go back. After several false departures, typical of the “Parade”, their number has however doubled, and, encouraging each other, finally, they come to a decision. Without turning round, in orderly groups, they slowly cross the beach with funny and serious professionalism of many parading little soldiers.

Then, the squad dissolves in the vegetation of the sand dunes, and everyone reaches quickly its nest, led by the chirping of the young and by the “contact cry” of the partner. Each individual has its own tonality of voice and, even if it can seem incredible, the Fairy Penguin has a sort of language.

Generally, “Uap, Uap, Uap” means “I am here” and at least three different sounds exist for expressing increasing levels of aggressiveness, from “Uuhuurr, Uuhuurr, Uuhuurr”, to “Weerr, Weerr, Weerr”. “Whii-huuu, Whii-huuuu, Whii-huuuuu” means, on the contrary, there there is a mating going on.

“Is it true”, I ask, “that, as we read in the books, the Fairy Penguins are faithful the whole life long?” “Devotion, that is mutual faithfulness”, Peter says, “is of the 80% per season. That is, every year, the 20% change partner because the companion has passed away, got lost at sea, or did not alternate properly in brooding and minding the young.”

“So, as an average, in five years, all the Fairy Penguins should have changed partner and in the ten years of their life, they should “marry” twice.”

“These are accurate data”, Peter goes on, “deducted from the identification small tags, visible nowadays, on the wing of almost all penguins. Placing rings is one of the most important of our activities. It has started in 1968 by the VORG (Victorian Ornithological Research Group), and they realized at once that the usual small ring on the foot was not fit for the short and plump paws of the Fairy Penguins. It was opted, therefore, for metallic bands, 6 mm. thick, to be closed at the base of the wing, in the place where this widens to form a fin. They have been installed to the chicks and last, normally, all the life.

It has been discovered that a female of the reserve still breeds at the venerable age of 21 years, and the young, after having left the nest, perform incredible displacements.

An only 13weeks old chick was found in the Kangaroo Island, which is more than 900 Km. far away. We still ignore why they go so much far, seen that there is plenty of fish also here, in front of the reserve, and we are doing two studies about this.

A team applies radio transmitters to young and adults, following them with a boat, another catches them and makes them vomiting, obliging them to drink a lot of water, in order to discover what they eat. Later, when we shall know exactly their habits and their preys, we shall revise, if necessary, our fishing methods with a law.

It was also discovered that the rate of mortality of the Fairy Penguins in the first three years of life is enormous, that is, before the animal reaches the sexual maturity. Most of them fall at sea, carried away by the lack of experience and the bad weather, but also on the dry land, many dangers, apart tourists, wait for them. Cats and snakes attack mainly the young, and the foxes make incredible carnages of adults.

“In one night only”, he continues, “a fox can kill even 30-40 of them just for amusement, and then eats only two or three of them. So, in order to protect the penguins, we decided to kill the foxes: between 1983 and 1984, in the reserve, we have eliminated more than 50 of them, and in 1985, for the first time, the number of Fairy Penguins has not decreased.”

“But, how many are they?”, I ask, curious.

“At least 20.000, 10.000 of which in position to reproduce, and 10.000 under the three years of age. They spend the winter in open sea, hunting anchovies and cuttlefishes, and between August and December, that is the austral spring-summer, about 5.000 specimen build a nest in the reserve.

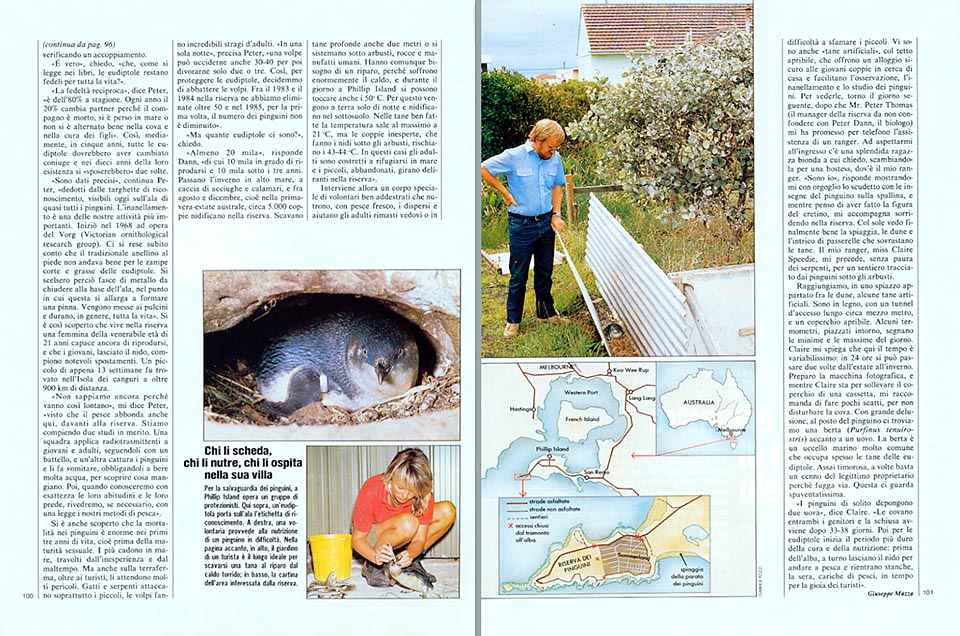

They dig dens deep even two metres, or they settle down under bushes, rocks, and human made objects. They need, however, a shelter, because they suffer enormously from heat and during the day, in Phillip Island, we can reach even the 50°C.

For this reason, they come ashore only by night, and they nidify under the ground. In well built dens, the temperature reaches the 22 °C at the maximum, but inexperienced couples, which make their nests under the shrubs, run the risk of the 43°-44 °C. In these cases, the adults are obliged to shelter in the sea, and the young, left alone, go around, like mad, along the reserve.

In this case, a special team of well trained volunteers intervenes, to feed, with fresh fish, the dispersed young and help the adults left widower or in difficulty, to feed the young.

There are also “artificial dens”, with an opening roof, which offer a sure accommodation for young couples looking for a house and facilitate the observation, the positioning of rings and the study of penguins.”

In order to see them, I come back the following day, after that Mr. Peter Thomas (the manager of the reserve, not to be confused with Peter Dann, the biologist), has promised me, by telephone, the assistance of a ranger.

This time, waiting for me at the entrance, there is a splendid blond girl in mini-short, to whom I ask, mistaking her for a hostess, where my ranger is. “It’s me”, she replies, showing me with proud and disappointment, the badge with the insignia of the penguin on the epaulette, and, while I think am appearing to be an idiot, escorts me, smiling, in the reserve.

With the sun, at last, I can see well the beach, the dunes and the entanglement of the gangways which stand above the dens. An athletic jump, and Miss Claire Speedie, my sexy ranger, is already down below, and recommends me to pay attention as to where I place my feet, while, loaded with cameras, flash and a sweater laced on my waist, “Fantozzi style”, I try to go down.

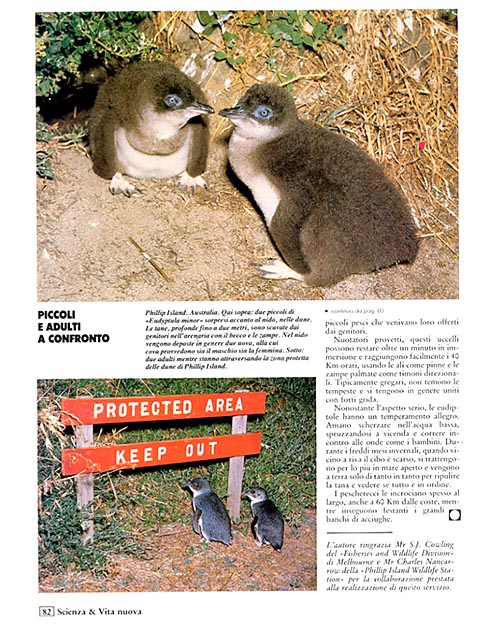

She precedes me, without any fear for snakes, along a path traced by the penguins under the shrubs and bows down, from time to time, to show me the nests. We reach, in a solitary place between the dunes, some artificial dens. They are made in wood, with an access tunnel long about half a metre, and an opening cover. Some thermometers, placed around, mark the minima and maxima of the day.

Claire explains me that here the weather is very unsettled: in 24 hours you can pass twice from the summertime to winter. She is happy to learn that I live in Monte Carlo, as her name is French, and she dreams, sometime, to visit the Principality. While I make ready my Hasselblad, she recommends me to effect only a few clicks, just not to disturb the brooding, and she raises the cover of a cage.

Surprise: instead of a penguin, we find a very frightened Muttonbird (Puffinus tenuirostris), with an egg, a sea bird, which often occupies the dens of Fairy Penguins.

“Penguins usually lay two eggs,” Claire explains, “parents brood them by turns, and they open after 33-38 days of incubation. Then, for the Fairy Penguins come the hardest time of the “caring and feeding”: before the daybreak, by turns, they leave the nest to go fishing and come back, tired, the evening, loaded of fish, in time for the joy of tourists.”

“It’s so since millennia, but, when this has become a performance?”

Claire smiles, embarrassed, she is too young, but they have told her that everything started 50 years ago, when, under the romantic moonlight, people was coming, with torch lights and lanterns, to see the penguins.

Later on, they have added the spots, the gangways, the stairs and the speaker, but the show, perfectly natural, has remained unchanged. “After all”, she says, “we have done nothing else than to get the birds used to the light of the spotlights.”

NATURA OGGI + SCIENZA & VITA NUOVA – 1986