Family : Callorhinchidae

Text © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

The Ghost shark (Callorhinchus milii Bory de Saint-Vincent, 1823) belongs, like the sharks and the rays, to the class of the Chondrichthyes, the cartilaginous fishes, to the order of the Chimaeriformes, an order of “living fossils” born in the Paleozoic, and to the family of the Callorhinchidae that counts only this genus and 3 species: Callorhinchus callorynchus, Callorhinchus capensis and our Callorhinchus milii.

Species similar in various aspects to the Spotted ratfish (Hydrolagus colliei), another Chimaeriformes that belongs, however, to the family of the Chimaeridae.

The genus Callorhinchus comes from the Greek words “kalos” (καλός) = beautiful and “rhynchus” (ῥύγχος) = snout, beak, with obvious reference to the trunk, whilst the specific name milii honours the memory of Pierre Bernard Milius, French navigator and naturalist, who in 1800 met Bory de Saint-Vincent on the occasion of the “Expedition to the Southern Lands” of Nicolas Baudin.

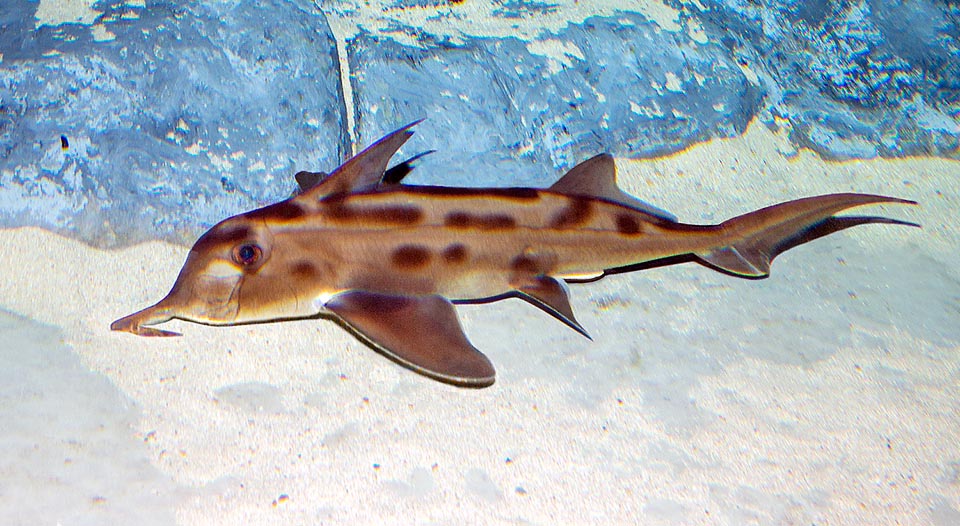

Callorhinchus milii is a cartilaginous fish belonging, like the Hydrolagus colliei, to the order of the Chimaeriformes, group of “living fossils” born in the Paleozoic © Giuseppe Mazza

Zoogeography

Callorhinchus milii lives on the continental shelf between the southern coasts of Australia and New Zealand.

Ecology-Habitat

It may be met at small depths, even in the mouth of the rivers, when in spring it leaves the deep waters to reproduce along the sandy coasts. It has been found even at 600 m, but usually it swims between the 30 and 200 m of depth.

Morphophysiology

Like Hydrolagus colliei, unlike the sharks, the Callorhinchus milii does not have scales and the gills are covered by a sort of operculum. It reaches a length of 125 cm with a silvery or brown with dark dots livery, and distinguishes easily from the other chimaeras due to the elongated snout with a sort of small sickle, spatulate like a plough, with which it explores the bottom.

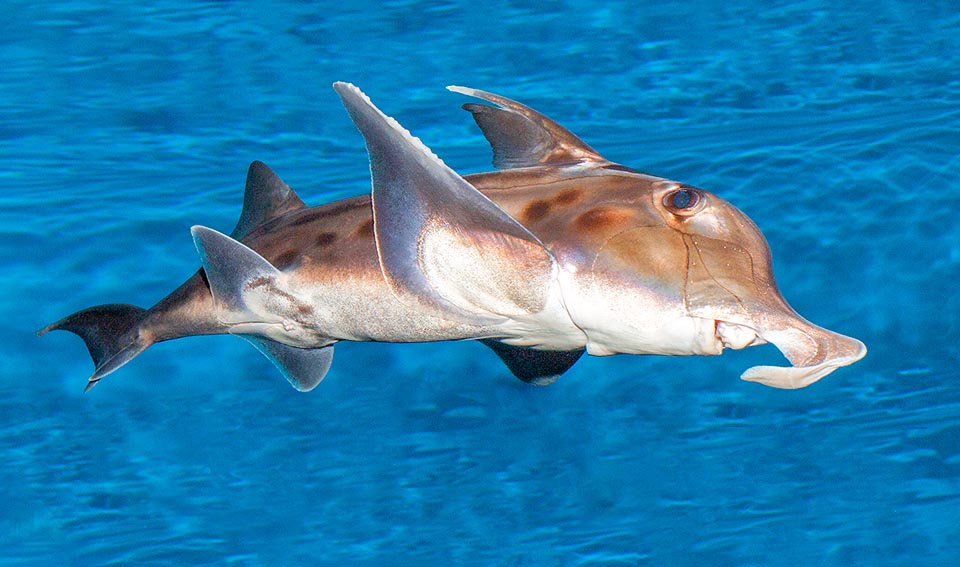

It easily distinguish from the other Chimaeras for the elongated snout, a sort of sickle, spatulate like a plough, with which it explores the bottom eating mainly crustaceans and benthic molluscs. Like the Hydrolagus colliei it has a showy spine, with defensive function but here it seems having no venom, close to the first dorsal fin © G. Mazza

Large pectoral fins, dorsal ones spaced and like Hydrolagus colliei we note a showy spine, close to the first dorsal fin, with defensive function. In this case it appears that it has no venom and also these males have on the head a small lumpy club for holding the female while mating, to which add, unique instance in the Chondrichthyes, two retractable pelvic clasps for a perfect grip.

Two couples of very solid teeth are placed on the upper jaw, whilst the two teeth of the lower jaw form practically a wide flat plate not less mineralized, a solid hammer for grinding the preys. Unlike sharks, they are not, therefore, sharp teeth to lose, replaceable in case of accident.

Ethology-Reproductive Biology

Callorhinchus milii nourishes mainly of crustaceans and bivalves, but also of small fish and various small benthic animals. It has big eyes but it finds them, also in perfect pitch darkness, thanks to its trunk, rich of sensors, capable to locate even the smallest movements on the bottom and the weak electric fields emitted by the preys.

It lives on the continental shelf between Australia and New Zealand, usually at 30-200 m of depth, but in the reproductive period, going from spring to autumn, these fishes gather along the coasts also in shallow and relatively salty waters, at the mouth of the rivers, thanks to particular anal glands that regulate its osmosis © Giuseppe Mazza

It is not a social fish, but, after the fishermen, in winter the nets contain only males or females, and this may lead to think that, apart the reproductive period, the two sexes live separate. Unlike Hydrolagus colliei, Callorhinchus milii is in fact fished for its edible flesh that, without too much respect for the Paleozoic, in Australia and in New Zealand, ends often on the small trays of the fast foods along with the chips.

During the reproductive period, going from spring to autumn, these fishes gather along the coasts also in relatively salty waters, thanks to particular anal glands that regulate the osmosis, where the females, that have a sac to conserve the sperm for several gestations, lay two eggs the time. They are yellowish horny cases, abandoned on the sandy bottoms, that progressively darken during the 6-8 months of incubation. The newborns, upon their birth, measure about 12 cm with a life expectancy of 15 years.

It is not a particularly endangered species today (2019), but resilience is weak, with a theoretical doubling of populations in 4,5-14 years, and the fishing vulnerability index marks 55 on a scale of 100.

Populations are stable and since 2015 Callorhinchus milii has been listed as “LC, Least Concern” on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

The females, having a sac to conserve the sperm for more gestations, lay two eggs at the time. These are yellowish horny cases, abandoned on the sandy bottoms, that darken progressively in the 6-8 months of incubation. The newborns upon their birth measure about 12 cm with a life expectancy of 15 years © Giuseppe Mazza

Curiosity

Callorhinchus milii is the first cartilaginous fish whose genome has been sequenced, because it was the smallest and hence the easiest of its group. About 450 million of years ago, the vertebrates and this fish, practically unchanged, had a common ancestor and some of its genetic sequences, compared with ours and those of the vertebrates, generally, have revealed useful for the study of the evolutionary mechanisms.

Synonyms

Callorynchus milii Bory de Saint-Vincent, 1823; Callorhynchus tasmanius Richardson, 1840; Callorhynchus australis Owen, 1854; Callorhynchus dasycaudatus Colenso, 1879.

→ For general information about FISH please click here.

→ For general information about CARTILAGINOUS FISH please click here.

→ For general information about BONY FISH please click here

→ To appreciate the BIODIVERSITY of CARTILAGINOUS FISH please click here.

→ To appreciate the BIODIVERSITY of BONY FISH please click here.