Petals folded like poppies with gorgeous or pastel colours. Shrubs of easy cultivation in Mediterranean climates. In the language of flowers they mean unfaithfulness and they hybridise easily.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

Cistous, in the language of flowers, means “unfaithfulness”, and, for once, this symbol appears to be well chosen.

In fact, the Cistus are not only unfaithful towards their own species, that is, they hybridize easily, but we can find even some hybrids of hybrids, with four parents, as it has been ascertained on the Côte d’Azur, by the National Institute of Agronomic Research of Antibes.

Typically Mediterranean plants, done for basking in the sun; about twenty species, of which only two, the Cistus symphytifolius, and the Cistus osbeckifolius, have left our sea for the sky of the Canary Islands.

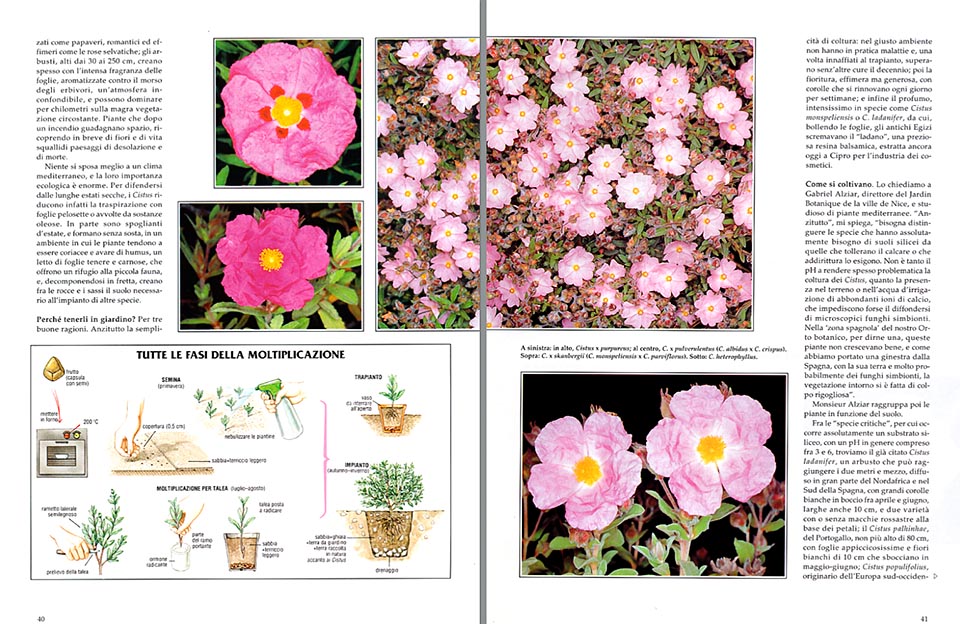

The flowers, white, pink or red, wide even 10 cm, with showy tufts of yellow stamens, are the most beautiful of the “bush” and of the “garigue”, rumpled like poppies, romantic and ephemeral like the dog roses; the bushes, high from 30 to 250 cm, create often with the intense fragrance of the leaves, aromatized against the bites of herbivores, an incredible atmosphere, and can predominate for kilometres on the meagre surrounding vegetation.

Heat-resistant plants, helped by the fire, which increases the germination capacity of their seeds, so much that, after a fire, they gain ground, covering, quickly, with flowers and life, bleak landscapes of desolation and death.

Nothing joins better a Mediterranean climate, and their ecological importance is enormous.

In order to defend themselves from the long, dry summers, the Cistus reduce in fact the transpiration with leaves, hairy or covered by oily substances, partially stripping in summer, and form, incessantly, in a habitat where the plants tend to be tough and stingy of humus, a layer of soft and fleshy leaves, which offer an important shelter to the minor fauna, and decomposing quickly, create, between the rocks and the stones, the soil which is necessary for the installation of other species.

Why to keep them in the garden?

For three good reasons.

First of all, the simplicity of cultivation: in the right habitat, they do not have practically an disease, and once watered at the transplantation, they can overcome, without any other cares, the decade; then the flowering, ephemeral, but generous, with corollas which renew every day for weeks; and, finally, the scent, very intense in species such as the Cistus monspeliensis or the C. ladanifer, from which, boiling the leaves, the ancient Egyptians skimmed the “labdanum”, a precious balsamic resin, extracted also nowadays in Cyprus, for the cosmetic industry.

HOW TO CULTIVATE THEM

We ask this to Gabriel Alziar, director of the Jardin Botanique de la Ville de Nice, and student of Mediterranean plants.

“First of all”, he explains me, “we must distinguish the species which absolutely require siliceous soils, from those which tolerate the limestone, or that even require same. It is not the pH to render often problematic the cultivation of the Cistus, but the presence in the ground or in the irrigation water of abundant calcium ions, which perhaps do not allow the propagation of microscopic symbiont fungi.

In the “Spanish area” of our Botanic Orchard, just to say, these plants did not grow up well, and as soon as we have carried a broom from Spain, with its soil, and most probably also some symbiont fungi, the vegetation all around has become, suddenly, luxuriant”.

Then, he groups me the plants after the type of soil.

Between the “critical species”, for which it is absolutely necessary a siliceous substratum, with a pH generally between 3 and 6, we find the previously cited Cistus ladanifer, a bush which can reach the 2 metres and a half, spread in most of North Africa and the south of Spain, with great white corollas, in bud between April and June, wide even 10 cm, and two varieties , with or without reddish dots at the base of the petals; the Cistus palhinhae, of Portugal, not high more than 80 cm, with very sticky leaves and with 10 cm white flowers, which bloom in May-June; the Cistus populifolius, coming from south western Europe and Morocco, high even 180 cm, with stalked leaves similar to poplar, covered, in June, by white 5 cm corollas, spotted of yellow in the centre; the Cistus psilosepalus, an Iberian species, even 150 cm high, with 4-6 cm white flowers which open in May-June; the Cistus monspeliensis, 50-150 cm high, spread in all the Mediterranean basin, Italy included, with very perfumed leaves and white small flowers, in bud between April and June; the Cistus salviifolius, with leaves similar to the sage, a small bush of 30-80 cm, spread over all Italy, with a distribution analogous to that of the holm oak, covered between April and June by bright 5 cm white flowers, with petals spotted of yellow at the base; the elegant hybrid x aguilari, born from the cross breed of C. populifolius with the C. ladanifer, high about a metre and a half, with white 7-8 cm corollas, in bud in June; and the hybrid x cyprius, born from C. laurifolius and the C. ladanifer, high even 2 metres, which blooms in the same period, with white 7 cm corollas, with crimson brown spots.

More tolerant towards the limestone, are, on the contrary, the Cistus creticus, a species very much polymorphous, widespread in all the Mediterranean, with various synonyms, such as C. villosus, C. incanus, and C. corsicus, high 30-120 cm, with a main flowering between April and June, and some sporadic red-lilac corolla all the year round; the Cistus heterophyllus of North Africa, with very variable leaves and medium-sized flowers, lighter than the previous ones, which bloom in April-May; the Cistus symphytifolius of Canary Islands, with 6-8 cm flowers, deep pink, in bud between April and June; and some garden hybrids in flower in spring, such as the Cistus x pulverulentus, high about 80 cm, with showy intense red purple corollas; the well known Cistus x purpureus, born from the C. ladanifer and the C. creticus, which can be more than a metre and a half high, with largae red petals, with a dark spot at the base; and the Cistus x skanbergii, a hybrid of the Cistus parviflorus, covered of cascades of small corollas, similar to small wild roses.

And there are, finally, two “counter current” species, which need calcareous soils: the Cistus albidus, high less than a metre, very common all over the Mediterranean, with medium size pink flowers, in bud between March and May, and the Cistus clusii, burdened in April-May of white small flowers, with a gait and leaves similar to the rosemary.

The soil, a mixture of sand, gravel, and garden soil, with some addition of sheep manure, must be, in any case, well drained, and, especially for the plants of the first group, it’s better to add some soil collected in nature close to the Cistus.

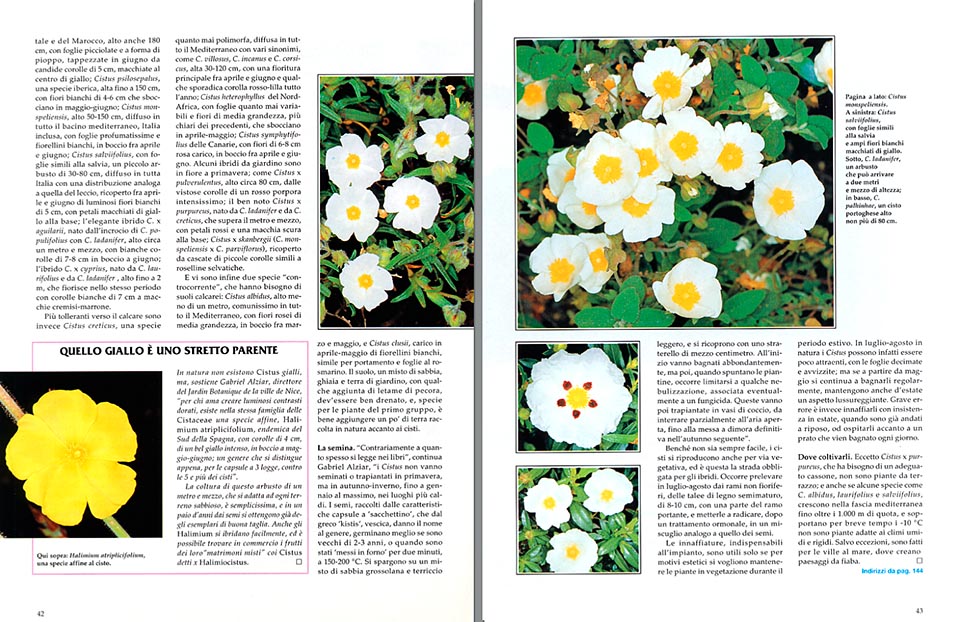

Contrarily to what often we read in the books, Gabriel Alziar continues, the Cistus are not to be sown or transplanted in spring, but in autumn-winter, until January, at most, in the warmest places.

The seeds, collected from the typical “small sack” capsules, which, from the Greek, “kistis”, vesicle, give the name to the genus, germinate better if they are 2-3 years old, or when, simulating a fire, they have been “put into the oven”, for two minutes, at 150-200 °C.

They must be scattered on coarse sand and light mould, and covered with a small layer of half a centimetre. At the beginning, they are to be abundantly watered, but later, when the small plants come out, we have to confine ourselves to some nebulization, associated, in case, with a fungicide.

These are then to be transplanted in earthen pots, to be partially interred in open air, till their final settlement in the next autumn.

Even if not always easy, the Cistus reproduces also in a vegetative way, and this is the compulsory method for hybrids. It is necessary to take off, in July-August, from not flowering branches, some cuttings of half-ripe wood, of 8-10 cm, with a part of the bearing branch, and place them to root, after a hormonal treatment, in a mixture analogous to the one of the seeds.

Watering, necessary for the installation, are useful only if for aesthetical reasons we want to keep the plants in vegetation during the summer period. In July-August, in nature, the Cistus can be, in fact, not too much attractive, with the leaves decimated and withered; but if, starting from May, we go on in watering them regularly, they maintain also in summer a luxuriant appearance.

Gross error is, on the contrary, to water them with insistence in full summer, when they have already gone to rest, or keep them close to a lawn which is watered all the days.

WHERE TO CULTIVATE THEM

Excepting, maybe, the Cistus x purpureus, which needs anyway a suitably large case, they are not plants for balconies; and also if some species, like the C. albidus, the C. laurifolius, and the C. salviifolius, grow up in the Mediterranean area till more than 1.000 metres of altitude, and bear, for short time, the -10 °C, they are not, usually, plants suitable for humid and rigorous climates.

Barring exceptions, they are mainly done for villas close to the sea, where they create, for some weeks, fabulous landscapes.

There are missing, it’s true, some yellow Cistus, but Gabriel Alziar concludes, “for he who loves to create bright golden contrasts, a similar species exists in the same family of the Cistaceae, the Halimium atriplicifolium, endemic in the south of Spain, with 4 cm corollas, of a beautiful deep yellow, in bud in May-June; a genus which can be hardly distinguished, for the 3 lodged capsules, in opposition to the 5 and more of the Cistus”.

The cultivation of this bush of a metre and a half, which adapts to any sandy ground, is very simple, and in a couple of years, from the seeds, we can already obtain some specimen of good size. Also the Halimuim, finally, hybridize easily, and it is possible to find on the market also the fruits of their “mixed marriages” with Cistus, called x Halimiocistus.

GARDENIA – 1992

→ To appreciate the biodiversity within CISTACEAE family please click here.