Each corolla a brides dress. The reasons and chemical content of the colour of flowers. Petals that change colour. The blue rose.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

The first thing which occurs to me, if I ask myself the why of the colours in flowers, is that it’s a matter of many “wedding dresses”.

Most of the plants, in fact, in order to reproduce, must be pollinated, and, for attracting insects and birds, during millennia of evolution, have invented flowers with strong scents and showy colours.

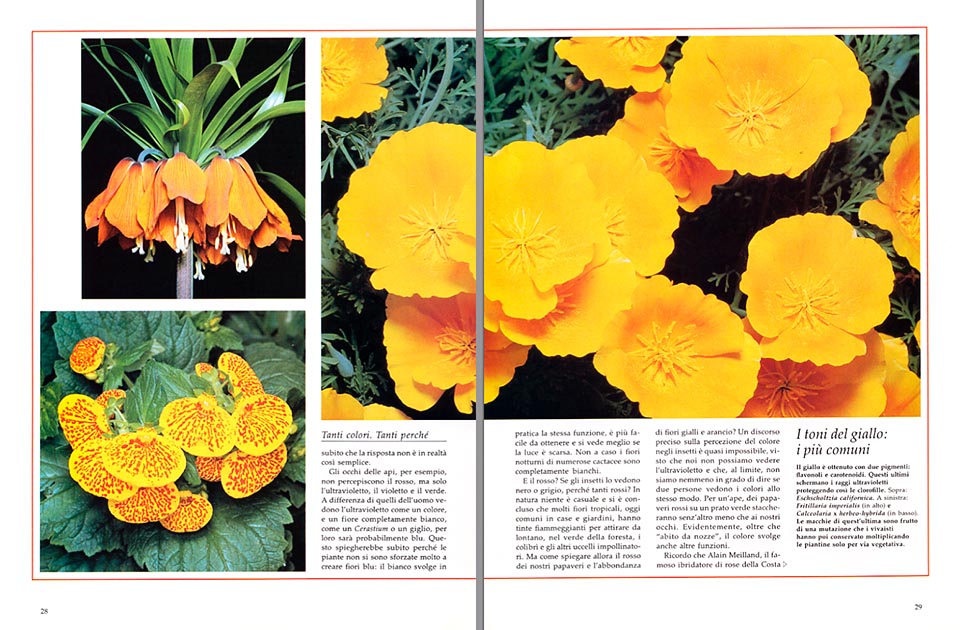

But, if I think for a moment , and consider that many insects practically see the world in “black and white”, or have a vision of the colour much different than ours, I realize immediately that the answer is not so simple. The eyes of the bees, for instance, do not perceive the red, but only the ultra-violet, the violet and the green.

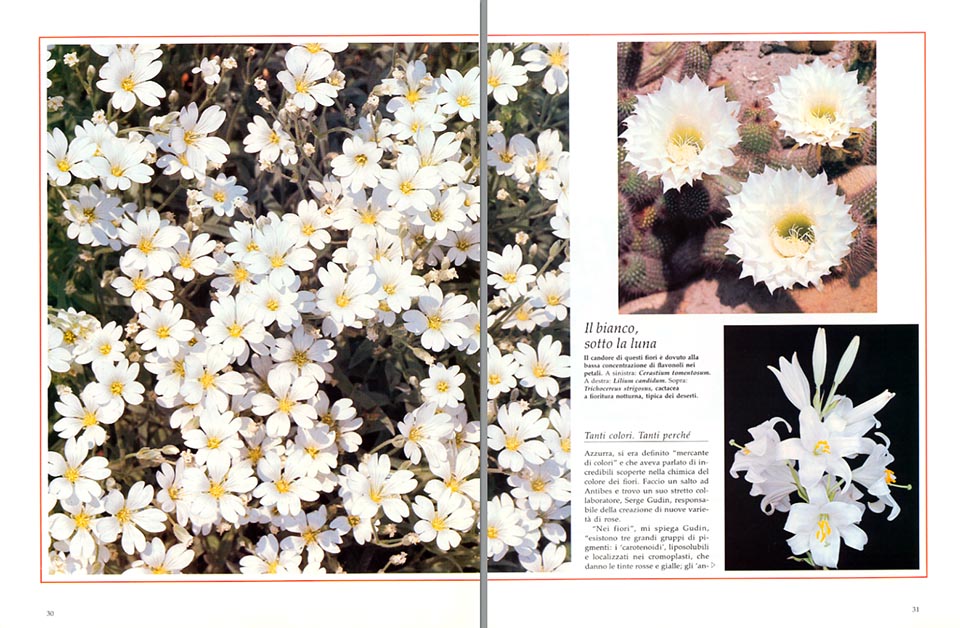

Unlike those of man, they see the ultra-violet like a colour and a completely white flower, such as a Cerastium or a lily, will appear, probably, as blue for them.

This would explain at once why the plants have done not many efforts for creating blue flowers: the white practically realizes the same functions, it’s easier to be obtained and can be better seen if the light is scarce.

It is not a case that the nocturnal flowers of many Cactaceae are completely white.

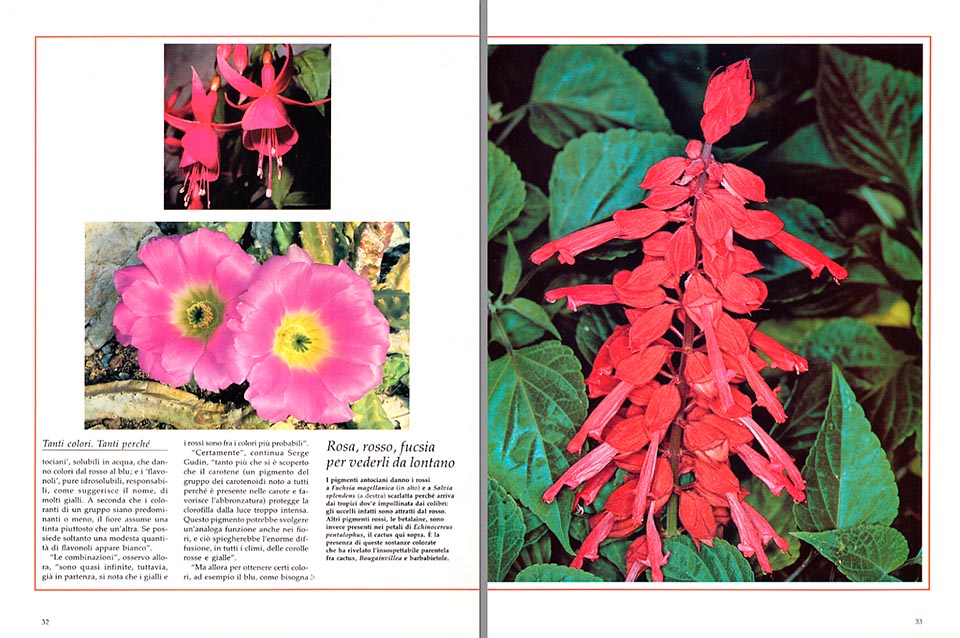

And the red? If the insects see it as black or grey, why so many red colours?

Nothing is casual in nature, and it has been concluded that many tropical flowers, nowadays common in houses and gardens, have blazing colours to attract from far away, in the green of the forest, the pollinating birds, which, unlike for our climates, are always going around there.

But, then, how to explain the red of our poppies and the abundance of yellow and orange flowers?

A final wording about the perception of colours in insects is almost impossible, seen that we cannot see the ultra-violet, and that we are not even in condition to say if two persons see the colours in the same way, but for a bee, some red poppies on a green lawn will stand out by sure less clearly than for our eyes.

Evidently, besides the function of “wedding dress”, the colour in the flowers has also other functions.

I remember that Alan Meilland, the famous roses hybridizer of the Côte d’Azur, in an interview I had done him time ago, had defined himself “a merchant of colours”, and that he had been talking with me about incredible discoveries done in chemistry regarding the colours of the flowers.

I go to Antibes, and find a near collaborator, Serge Gudin, responsible for the creation of new varieties of roses.

“Among the flowers”, he explains to me, “there are three huge groups of pigments: the Carotenoids, lipophilic and located in the chromoplasts, which give the colours red and yellow, the antholyanins, water-soluble, which give colours from red to blue, and the flavonols, water-soluble too, responsible, as the name suggests, of many yellow colourings.

Depending if the colouring agents of a group are prevailing or not, the flower assume a colour instead of another. If it has only a modest quantity of flavonols, then it appears white”.

“The combinations”, I remark then, “are almost endless, but it can be seen at once, already from the beginning, that the yellow and red colours are the most probable ones”.

“Sure”, Serge Gudin goes on, “also because it has been discovered that the Carotene (a pigment of the group of the Carotenoids, known to all because because present in carrots and helping in tanning), protects the chlorophyll from the too much strong light.

This pigment might perform a similar function also in the flowers, and this would explain the enormous diffusion, under all climates, of red and yellow corollas”.

“But then, for instance, a husbandman wishing to get certain colours, like the blue, what has he to do?”, I ask, ever more curious.

“Inside each group”, he explains to me, “we can distinguish various pigments. They have definite names, often derived from the flowers which contain them in a predominant way.

The hybridizer knows that, if in the flower where he is working, certain pigments are missing, he will never be able to obtain certain dyes.

This applies for the famous blue rose: the roses do not have the delphinidol, the typical pigment of the Delphinium, and whatever cross-breeding we do, a blue rose will never be obtained.

It’s just like if with red and yellow pencils, we would like to paint a blue sky. The only way for doing this, is to get a pencil of that colour.

In American laboratories, they have been able to give the Delphinidol to a poplar, which of course doesn’t have it, and the plant has begun to produce blue leaves.

In Japan, they have been able to include it in the genetic patrimony of the rose, but the blue, at the moment, is covered by other colours, and the outcome is deceiving”.

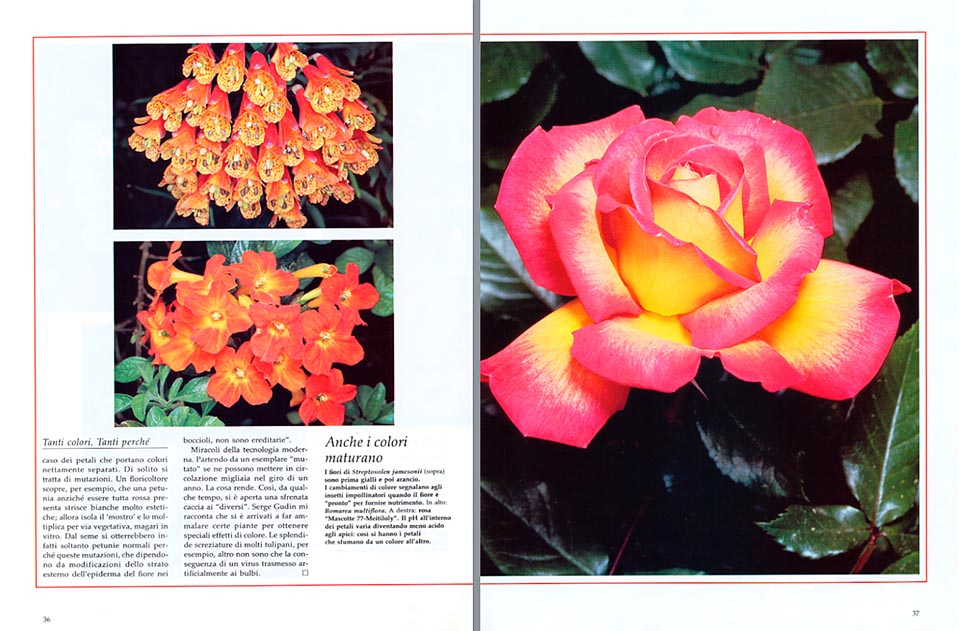

I think, therefore, that one day, we shall have also the mythical blue rose, and I ask my interlocutor how they obtain flowers with changing colours, or with various dyes, well separated, in the same corolla.

“We have to say, first of all”, he replies, “that the same pigments, depending on the PH, give different colours. So, the flowers with petals which tone down in different dyes towards the apex, are obtained by selecting plants where the PH changes, inside the petal, from the base to the apex.

Similarly, we can explain the changes of colour of a single flower in the time. With the ripening, in fact, the pH can change and therefore, a yellow can become an orange or even a red.

Also the temperature has an important role. If, for instance, in a greenhouse it decreases too much, we can have an excessive concentration of certain pigments and a red rose can become almost black.

Very different is the case of the petals which have colours distinctly separated. Usually, it’s matter of mutations.

A floriculturist discovers, for instance, that a petunia, instead of being all red, has some very aesthetic white stripes, and then isolates the “monster”, and multiplies it in a vegetative way, maybe in vitro. From the seeds he might get, in fact, only normal petunias, because these mutations, which depend from modifications of the external coat of the epidermis of the flower in the buds, are not hereditary.

Miracles of modern technology, which allows, by the time of one year, starting from a modified specimen, to circulate thousands of them!

The thing is worthy, and so, sine some time, a wild chase to the “different” ones has started”.

While I thank him, satisfied, Serge Gudin tells me that they have even reached the point to get sick some plants in order to obtain some effects of colour. The splendid specks of many tulips, for instance, are nothing else that the consequence of a virus artificially transmitted to the bulbs.

GARDENIA – 1986