This is a real oddity. It has the muzzle of a duck but the fur of a beaver, it lays eggs but suckles its babies, it is gentle but can deploy a poisonous spur, it falls ill from minimal stress but has lived from time immemorial. Everything on this puzzle of nature.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

There are animals, like the scorpion, suitable for every geological “season”, and practically unchanged since 400 millions of years, but the most part of the living beings, has a suffered history, where well-suited intuitions, and successive reconversions interlace with hard struggles and failures.

Blind alleys of the life, extinct species, quickly deleted by an evolution which never proceeds in a direct line, which never closes all the doors, and goes forward reeling, by attempts.

Almost always, the origins hide under the beginnings, and the “prototypes”, generally don’t leave any trace in the fossils.

We know that birds and reptiles are near relatives; but these had to be quite different from the present ones, and when, 200 millions of years ago, the first mammals tried new ways, the separations between the groups were not too much definite.

Hot blood reptiles, furred birds, mammals which lay eggs: reality had surely to overcome our imagination, even if not too much has remained of all these forms passing by.

It’s like if, within hundred millions years, somebody would like to look for the marks of our civilization among the fossils of a car: by sure he could find the bonnet of the Volkswagen, some parts of a mini and some super mini cars, produced for years in large quantity, but couldn’t find any trace of the prototypes, the cars by Cugnot, Stafford or Panhard.

And yet, still now left alone in the Australian region, do live some “mammals in transit”, incredibly survived, flesh and blood, to the competition of developed species.

They are all oviparous, classified in the “monotremes” (literally, “unique hole”), because, as for the birds, the amphibians and the reptiles, the tract of their urogenital apparatus and the alimentary duct converge in only one hind orifice, called cloaca.

“Monotremes oviparus, ovum meroblastic”. It’s the famous wire, with which, in 1884, the scholar Caldwell, informed the Zoological British Society, gathered in Montreal, that the Duck billed Platypus, (Ornithorhynchus anatinus), lays, as birds do, eggs with yolk.

And when the first specimen, embalmed, arrived in Europe, many, at the British Museum of London, thought it was a joke: a beaver with a bill similar to the one of a duck, two small eyes and web footed, by sure, did not look true.

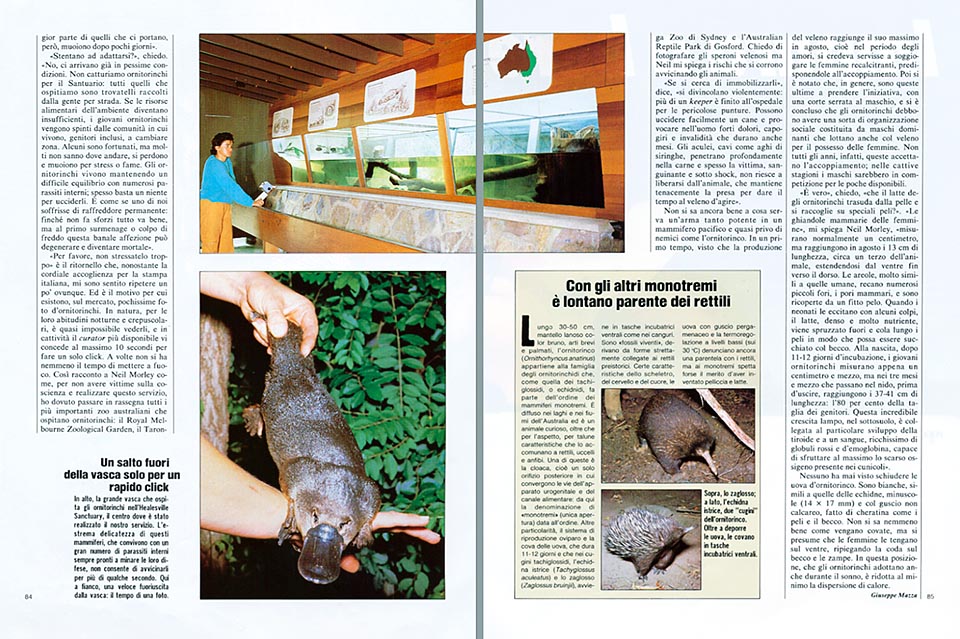

“And, furthermore,”, explains to me Neil Morley, director of the famous Sir Collin MacKenzie Sanctuary of Healesville, Australia, the only site in the world where these animals have reproduced in captivity, “males have, like serpents, on the back paws, a venomous gland connected to a spur.”

This huge zoological park, dedicated to Australian fauna, has the best equipped “Platypus house”, in the world. A complex with a large exposition basin, where swims, at fixed timings, a couple of duckbills.

Large wall panels narrate their life and anatomy, while a loudspeaker explains, in simple wordings, the biology and behaviour of these incredible animals to visitors. Two tunnels, just over the surface of the water, lead to the artificial dens placed in the rear of the building, in a calm area, closed to public, and another succession of tunnels connects them with some pools under the open sky, covered by a grating.

While I am observing them, guided by the director, an attendant comes, raises the grating, and throws inside the contents of a bucket. It looks like rubbish, and I ask, curious, what it is.

“It’s the meal for this night,” Neil Morley explains, “based on fresh water crayfishes, flour larvae, and boiled eggs, kneaded with some milk, yoghurt and vitamins.

In nature, duckbills feed mainly of crustaceans, worms and larvae of insects they find on the river-beds, eyes closed, with their very sensible beak, rich of nervous terminals. They collect them, as hamsters do, in two big pockets in the cheeks, and then come to surface, swallowing the booty, with a splash.

They are not hard to please, and adapt themselves,

surprisingly, to any food available. In the river Thredbo, for instance, where in wintertime the temperature is very low, and they need an important energetic contribution, they do not follow any more the diet used for millennia by their ancestors, but they eat the eggs of the trout introduced, recently, by man. And here, with us, they get immediately accustomed to this odd menu, result of long experiments.”

Then he tells me how, in 1943, they have been able to reproduce them.

The director at the time, David Fleay, had placed a young couple, Jack and Jill, in a complicated enclosure, which include, besides the usual pool, a thick layer of soft land where to dig the den.

When 6 years old, Jack started courting the companion, swimming with it in circles and embracing it with the tail, according to the amatory ritual of duckbills. Then, by October ending, Jill disappeared into the nest, and came out four months later, exulting, escorted by the young.

“And, generally, how long do they live?”, I interrupt him.

“In nature, about 12 years, but Jack reached the 17; the maximum recorded in captivity, and Jill approached the 10. Now, we have two specimen, well settled, 2 and 7 years old, but the largest part of those taken here, die after a few days.”

“Because they have difficulties in adapting?”

“No, simply because when they get here, the are already in very bad conditions. We do not hunt duckbills for the sanctuary: our guests are all foundlings, picked up by people along the roads.

There is a tight relation between the environment, with its alimentary resources, and the number of duckbills. And when food is running short, young specimen are compelled to change area. Some of them are lucky, but most of them do not now where to go: they get lost and die for starvation or due to stress.

Duckbills maintain a difficult balance with various internal parasites, and often a “nothing” is sufficient to kill them.

It’s like one of us should live with a “permanent cold”: as long as we do not make any effort, all is in order, but, if we overwork, or upon the first cold, this trivial disease can become fatal.”

“And the poison?”

“Surely,” Neil Morley goes on, “it’s a heritage from reptiles. When we try to immobilize them, the males flounder furiously and more than one “keeper” has gone to hospital due to their dangerous stings.

They can easily kill a dog, and in the man they cause strong pains, , giddiness and invalidity, more or less serious, which can even last several months.

The stings, hollow like the needle of a syringe, penetrate the flesh deeply and often the victim, bleeding and under shock, is even unable to take off the animal, which keeps persistently the grasp, in order to allow the poison to enter.

We still do not know what’s the use of such a powerful weapon, in a pacific mammal, and without foes, as the duckbill is.

In a first moment, seen that the production of poison increases in August, during the period of heat, it was thought that its use was to “subdue” the reluctant females, thus predisposing them for the pairing.

Later on, it has been noted that, usually, it’s the females which take the initiative, with a heavy courting, and it has been therefore concluded that, or it’s a weapon nowadays useless, born in past to fight enemies now disappeared, or that duckbills

have a sort of social organization with some dominant males which struggle, with the poison, for the possession of the females.

These ones, in fact, do not reproduce regularly, and in the “bad” years, should be somewhat contended.

“But is it true,” I ask, “that they do not have teats and that they perspire the milk through the skin?”

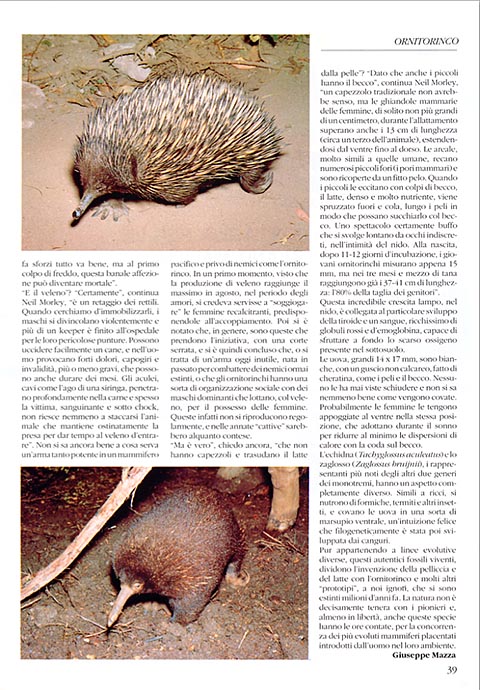

“Since that the young have the beak,” Neil Morley goes on, “a traditional teat would have no meaning, but the mammary glands of the females, usually not bigger than one centimetre, during the lactation are more than 13 cm long (about one third of the animal), extending from the abdomen to the back.

The areolae, very similar the the human ones, have several small holes (the mammary pores), and covered with thick hair. When the young excite them with hits of the beak, the milk, thick and very nourishing, is sprayed out and flows along the hair, in such a way that they can suck it with the beak.

A certainly funny performance which takes place far away from indiscreet eyes, in the privacy of the nest. When just born, after 11-12 days of incubation, young duckbills measure only 15 mm, but after the three and a half months spent in the den, they reach already a length of 37-41 cm: the 80% of their parents size.

This incredible flashy growth in the nest, is connected with the particular development of the thyroid, and to a blood, very rich of red blood cells, and of haemoglobin, capable to exploit completely the scarce oxygen present in the subsoil.

The eggs, measuring 14 x 17 mm, are white, with a non calcareous shell, made of keratin, like the hair and the beak.

Nobody has ever seen them opening, and we don’t even know well how they are brooded. Probably, the females keep them placed in the belly, with the tail bent on the beak, the same position they employ during the sleep, in order to reduce to the least any heat dispersion.

The echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus), and the western long-beaked echidna (Zaglossus bruijnii), the best known representatives of the other two genera of monotremes, have a completely different appearance. Resembling to hedgehogs, they feed of ants, termites, and other insects, and brood their eggs in a sort of ventral marsupium, a fortunate intuition, which will be, later, developed by kangaroos.

Even if they belong to different evolution lines, these authentic living fossils, share the invention of the fur and the milk with the duckbill, and many other “prototypes”, unknown to us, which have disappeared millions of years ago.

Nature surely is not tender with pioneers, and, at least in liberty, also for these species, the hours are numbered, owing to the competition of the more developed planctate mammals introduced by man in their habitat.

NATURA OGGI + SCIENZA & VITA NUOVA – 1986