A terribile infection has spread among these animals, also causing females to become sterile. Sensational sequence of the second birth of a koala who comes out of the pouch and kisses its mother.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

“Be careful! Maybe it’s a snake!”, I cry to Roberta, the student in biology who accompanies me along this trip.

I seize the Hasselblad, while something moves at the foot of a colossal “Blackboy” (Xanthorrhoea sp.), the centenarian “Grass plant “, which has drawn our attention for its candid, two metres long, cylindrical inflorescences.

We are in Australia, at the borders of the Lamington National Park, not far from Brisbane, in Queensland, in a forest of eucalypti, broken by the bright windings of an asphalted road, which ascends to more than 1.000 metres, towards the Mount Tamborine. Seven years ago, this was just somewhat more than a mule-track, and was leading, with thousands of jerks, to a small alpine hut in the rainy forest. Today, in some stretches, it looks like a motorway, and the hut has become an almost snobbish hotel: prices multiplied by four, rooms booked months in advance, buses with notices of organized tours, and hurried tourists, coming from the other side of the ocean, who continuously arrive from the Capital.

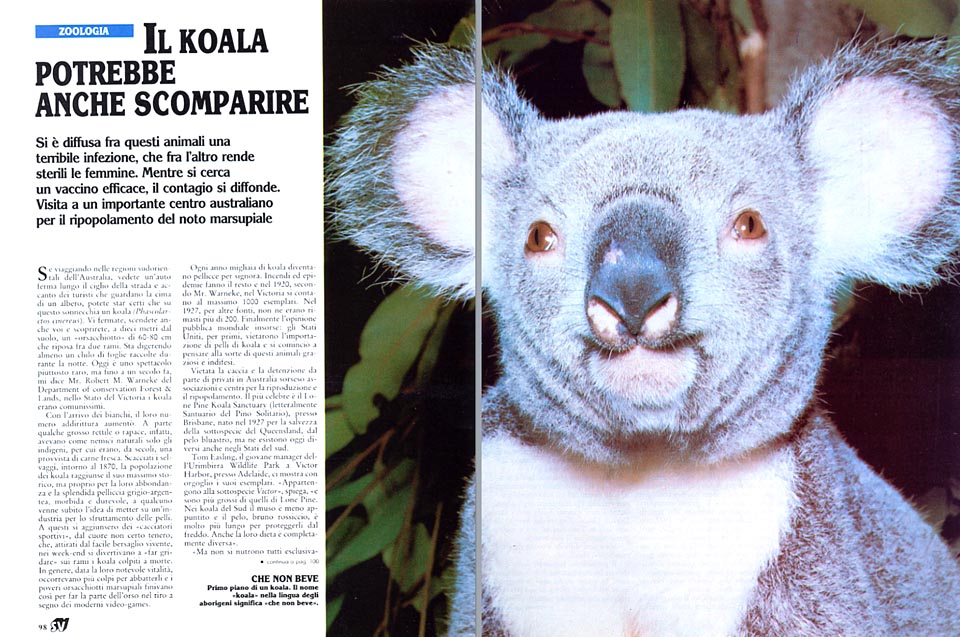

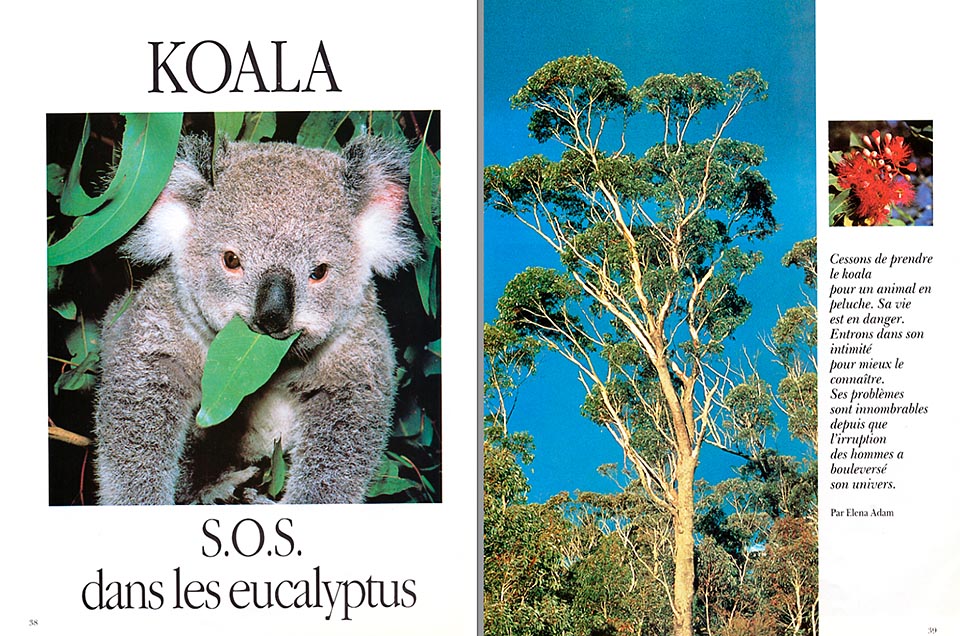

While the umpteenth roaring convoy passes by, our “snake” gives a start. We see some hair, and immediately we think it’s a rabbit, which, however, quite oddly, doesn’t run away. Roberta remarks me some dots of blood on the grass, and, further on, on the ground, we find a koala (Phascolarctos cinereus); agonizing.

It’s blind, but can still hear us, it lifts the head with difficulty, as to look at us, opens a frightening bleeding eye. The other one, since time, is by now glued by pus. It’s the Chlamydia, an epidemic disease, which attacks also man. It would be a charitable thing to kill it, but that’s beyond us, and after having left on the road a mark of reference, we look for the nearest rangers station.

It’s located just in front of our hotel. A huge parking area, stolen to the forest, faces the new wing of the lodge, while several waitresses, all wearing nice uniforms, cram reach aged tourists.

Luckily, the forest looks unchanged, even if the uncertain paths of old times, now vaunt steps, small areas for barbecue, and touching “public garden” benches, heroically defended against the attacks of humidity and plants. Fashionable notices, which could be envied by the Swiss, indicate the distances and the compulsory excursions: “Blue Pond”, “Morans Waterfalls”, “Pythons Rocks”, and even a “Tour for retired people”.

At last, we find a ranger: he struts about with the American tourists, which are offering sweets to the Crimson Parrots, (Platycercus elegans), of the forest, and sips, among badly repressed belches due to a copious meal, a cup of tea.

“A koala dying for Chlamydia along the road?” he repeats, “yes, yes, we know, there are many of them”. And suggest us to hurry up for lunch, as it’s almost two o’clock, and we run the risk of missing the service.

“I will come later and you will explain me where it is”, concludes, reassuringly, but we shall not see him any more.

Roberta does not talk, has difficulty, like me, in gulping down the bits. Once unloaded our baggages, we go back to the koala, which, in the meanwhile, has passed away. The bleeding eye is closed for ever, and a dot of white pus, between the hair, marks the end of the illness.

The following day, at the University of Brisbane, with Professor Frank Carrick, responsible for a vast research programme about this. Our narration does not surprise him.

“The degradation of the habitat, explains, “is the main cause for the Chlamydia. All the epidemic diseases which have affected the koalas in 1890, 1920, and 1930, are closely connected with the “habitat alienation”: houses, roads, industries, and human installations.

Koalas are very sensitive animals, which endure quite well the “acute stresses”, a dog barking under their tree, for instance, but not the “chronic stresses”, like the coming and going, exhaust gases, and the uproar of mass tourism.”

“But then”, I interrupt him, “how are they able to stay on the arms of tourists for those classic photographic souvenirs?”

“Those”, he goes on, “are particular koalas, born in captivity since generations, and used, from their birth, to the presence of man. By now, the consider normal to be handled and they don’t get stressed any more. But, in nature, where koalas are often sound bearers, in a continuous, difficult, balance with various parasites, the smallest thing is sufficient, and they die.”

“But exactly”, I ask, “what is the Chlamydia?”

“It’s not a virus, as many believe, but a very small bacterium, which like viruses, spends most of its life inside the cells of the host.

Two species do exist: the Chlamydia trachomatis and the Chlamydia psittaci. The first one, typical of human being, presents at least a dozen of immunotypes, causes arthritis, conjunctivitis, and is the main reason for women sterility. At least 500 millions of persons are affected, and, above all, in Asia and Africa, it’s the origin of several blindnesses (Trachoma). The animals are bearers of the Chlamydia psitatci, which can, exceptionally, infect man.

“It’s the famous Psittacosis”, I comment, thinking to the pulmonary sickness, which is caught from parrots, pigeons, and, generally, the birds kept in poor hygienic conditions.

“Sure, but it attacks also cattle and sheep, causing miscarriages and serious arthritis. At least two species of Psittaci hit then the eyes and the uro-genital organs of koalas”.

“And can they infect also man?”

“Theoretically, yes, but, practically, there is no knowledge of such cases. I handle continuously sick animals, and I have never caught anything. They are parasites extremely specialized, so that the form which renders koalas blind does not attack their genital organs, and the one which renders them sterile, does not hit the eyes.”

He shows me a small map, indicating the diffusion of the disease in the various states of Australia. Practically, there are no populations untouched, and the spreading of sterility is impressive.

“After a radiographic examination, made on 237 adult females, 43% are sterile, with peaks, in some areas of the 75%, and even 100%. An alarming element, if we think to the exiguity of present populations, after the massacres made by men during the first decenniums of the century, when, in the market of London, they were selling even 2 millions of hides of koalas per year, under the names of “Adelaide Chinchillas”, or, “Australian Beavers”.

“But, can they extinguish?”, I ask worried, “and, how many are, nowadays, the existing koalas?”

“Incredible as it may seem”, Prof. Frank Carrick goes on, “we know almost nothing about such a popular animal like the koala, which is even the emblem of Australia.

If you tell me that now, in Australia, there are 10.000 specimen, I can reply that they are not so many, but that probably, you are right; if you tell me that they are 10.000.000, I will tell you that I think that it’s too much, but you could even be right. The number, in any case, is in net diminution.”

“And you do nothing?”

“The government has created a research committee, to which I belong, to set forth effective laws for the survival of this rare, really unique, marsupial. Since about eight years, we are doing very serious studies on the numerical consistency of the various populations, of their social structure, the movements, the feeding, and the Chlamydia.

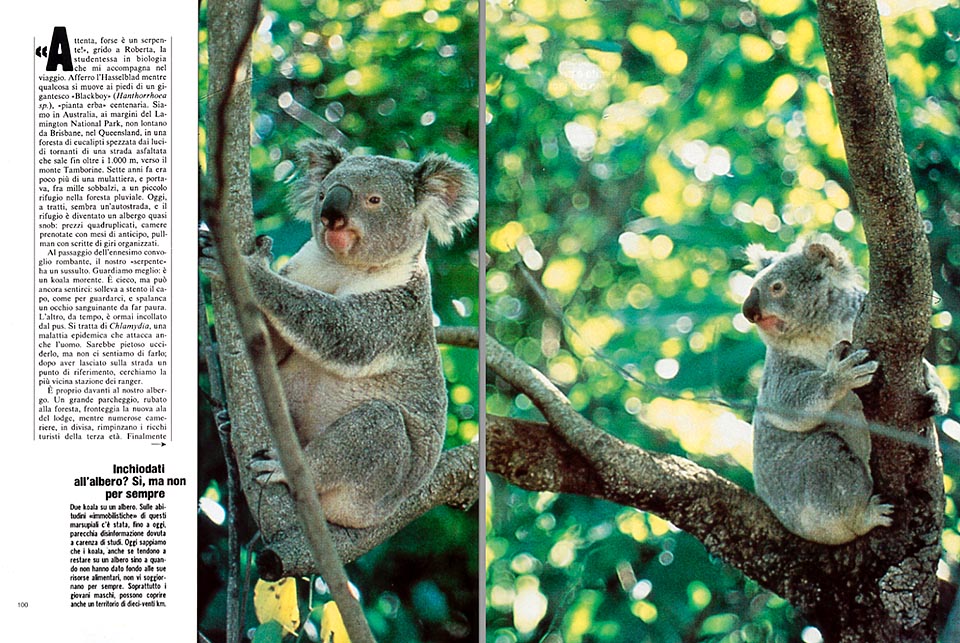

Many beliefs of the past, such as the idea that they do not drink, they never move, and feed almost exclusively of eucalyptus, have been all denied by facts. We have discovered that young males, instead of passing their life on a tree, can even travel for 10-20 km. Reserves, therefore, must not be small and dispersed, as it often happens now, but connected and as large as possible.”

And the vaccine against Chlamydia? I ask again, “there are rumours that you are trying to do something.

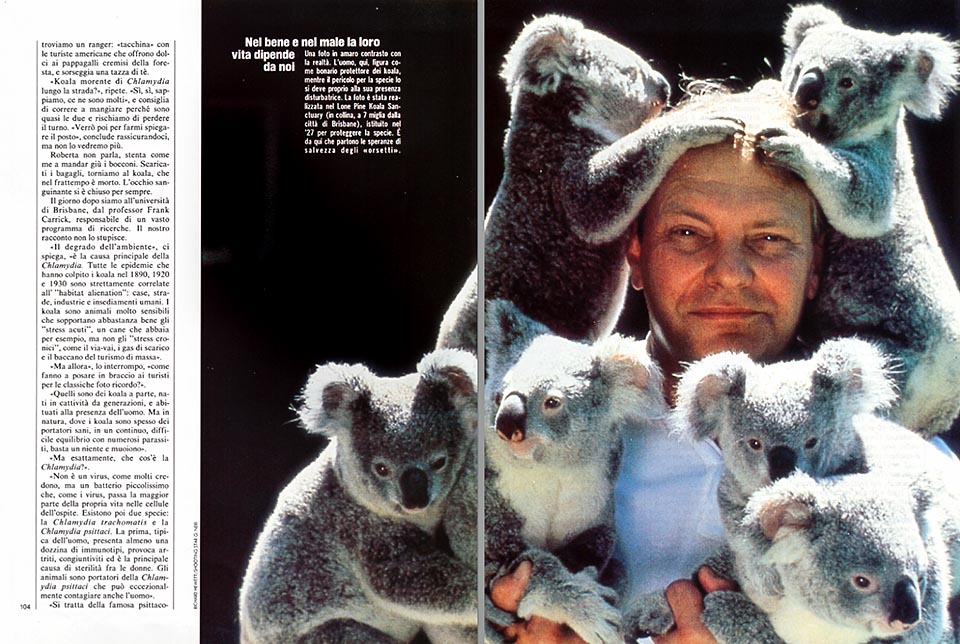

“The Lone Peak Sanctuary”, he continues, “is carrying on tests about, mainly useful for the captive animals. But, seen that the bacterium appears in various manners, the way to cover is very long. Besides, in spite of the millions of dollars allocated, even the vaccine for man has not yet been found.

And then, even if this theoretically could be possible, I am contrary to mass vaccination for the animals in liberty.

The immunogenic mechanism of koalas is very complicated: while in other mammals the antibodies develop after two weeks, for the koalas they need even 4 months, and I don’t know how they would respond to the vaccine.

By the end, they would result all positive to the serum, and we might not be able any more to understand, through the blood tests, which populations are infected, and which ones not.

Better to follow, for the moment, the way of antibiotics. In the man, usually, 3-4 weeks of doxycycline, for koalas, we use tetracycline, such as the Oxytetracycline.

At the beginning, it was thought that the antibiotics, by destroying the symbiont bacteria which disintegrate the cellulose, would practically lead the koalas to death for starvation. Then, it has been discovered that, unlike kangaroos and sheep, only the 9% of their diet is based on cellulose: they draw directly the energy from the carbohydrates, from proteins and from the lipids present in the leaves. Symbiont bacteria, instead, have important anti toxic functions, and it seems that they neutralize many poisons of the eucalyptus.

To sick subjects, which are taken here from the various national parks, we inject antibiotics once a week, and besides, usual eucalyptus leaves, we give them an integration of nourishment, a “supplementary food”, made of soya-beans and easily digestible lipids for children, after an odd formula realized by Tony Wood, the veterinary surgeon of the Lone Pine Koala Sanctuary. At least the 50% is saved.”

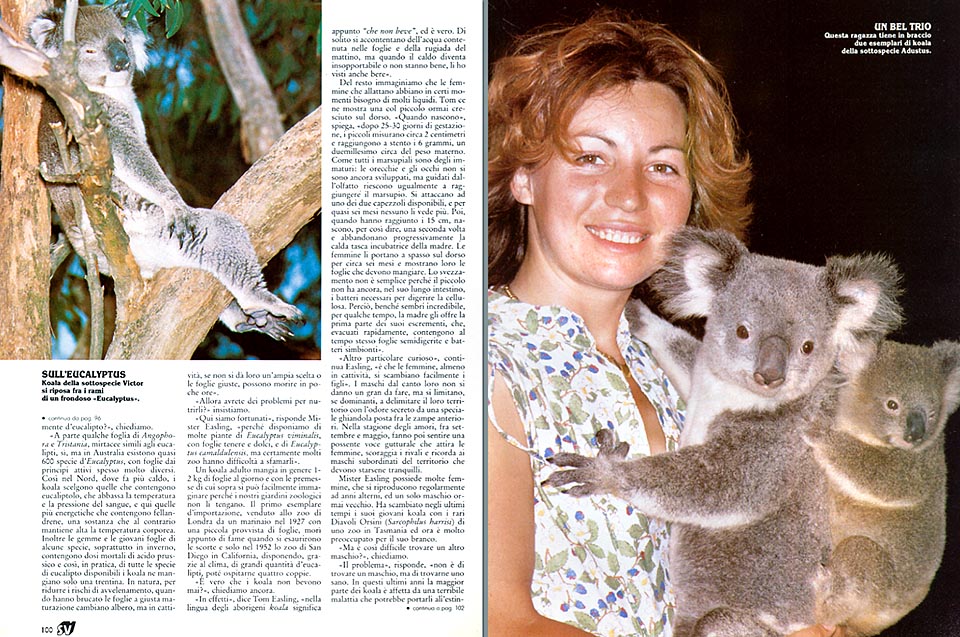

During the afternoon, we visit the Sanctuary, the most important centre for the reproduction of koalas in captivity. Created in 1927, it has enriched of other animals, and nowadays it’s a huge park-zoo of the Australian fauna.

At first, we meet an Alsatian dog, with on the back a koala, and this renders happy a group of Japanese tourists, and then, Pat Robertson, the energetic, very busy manager of the Sanctuary, 200.000 visitors per year, 85 adult koalas, with 8 domestic generations, on his shoulders.

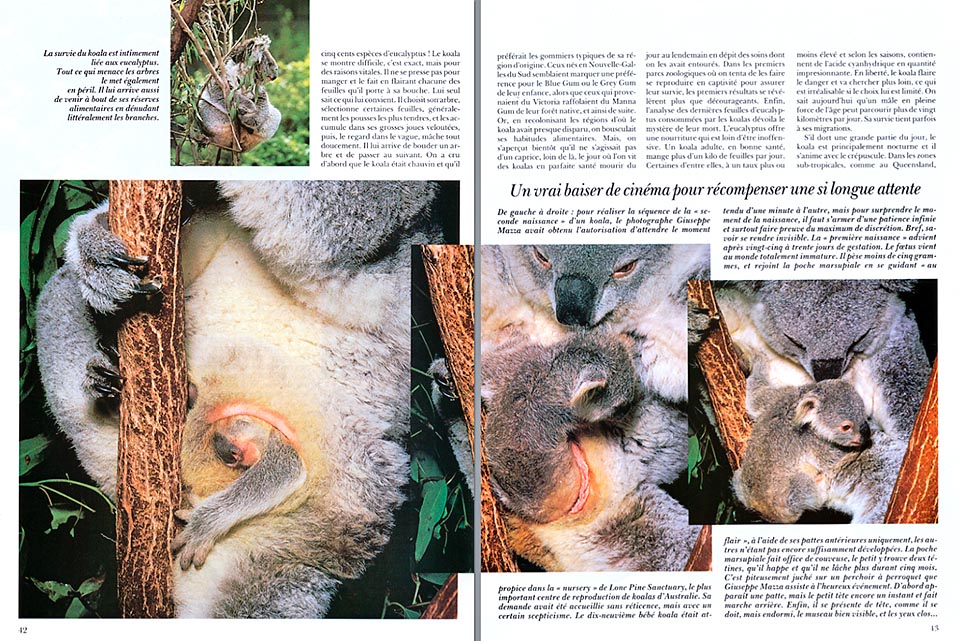

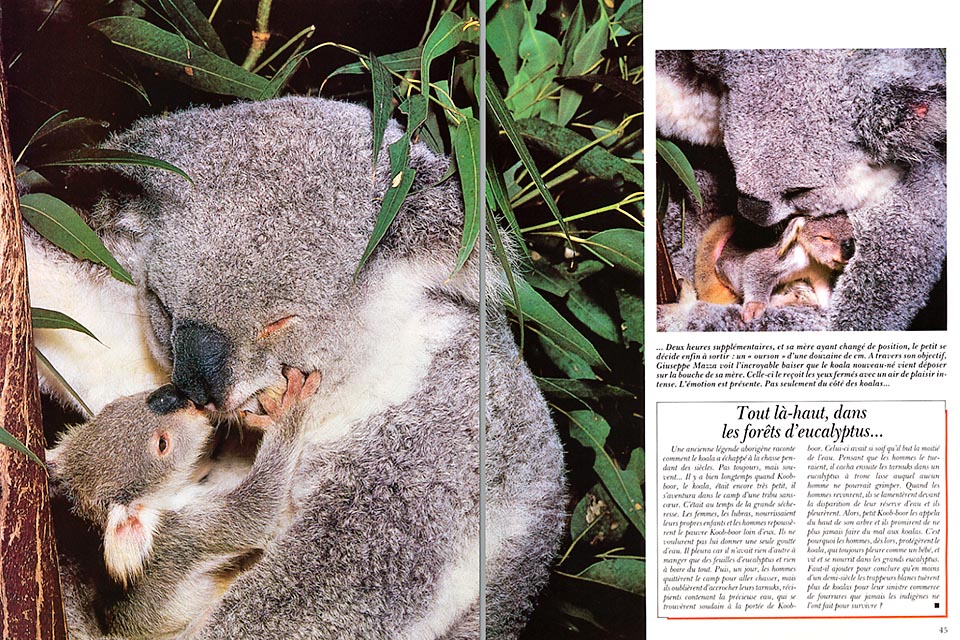

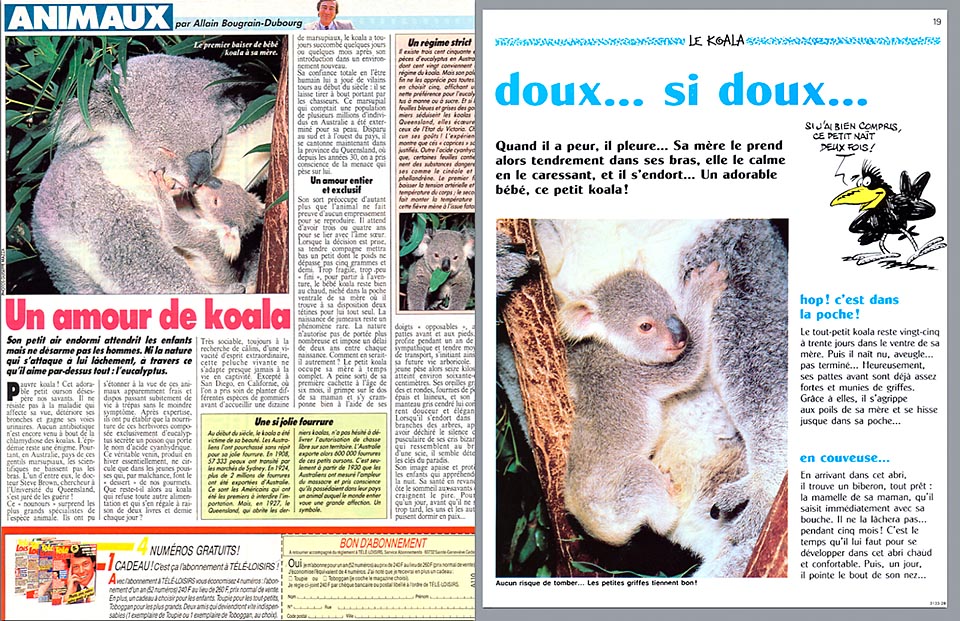

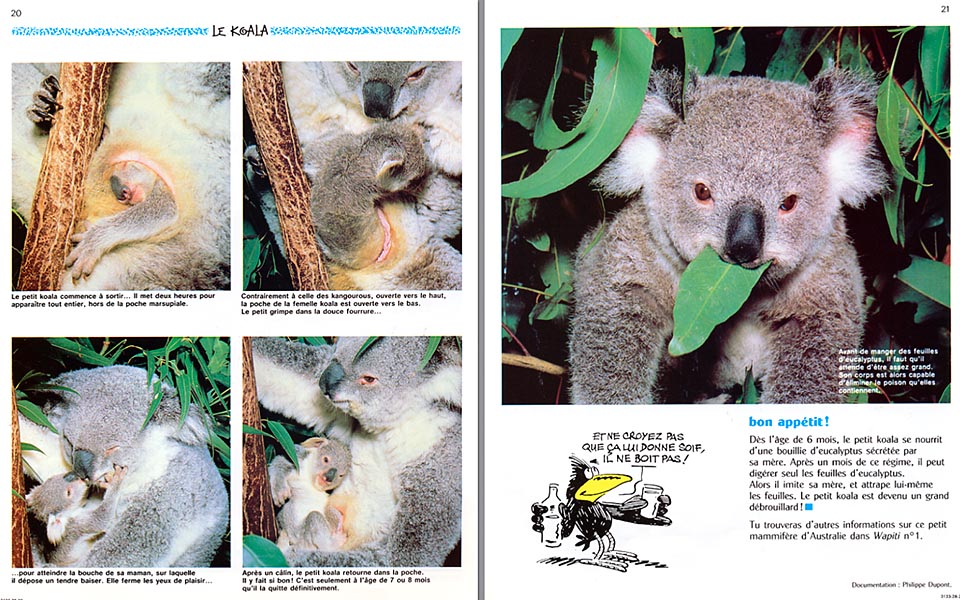

Like all marsupials, koalas come to birth premature, after 25-30 days of gestation. They weigh less than 5 grams, and guided by the smell, they take shelter for 5 months in a sort of incubator, a pouch with two nipples. But, as this opens downwards, hidden by the hair, and the young, unlike kangaroos, enters and gets out only for a few days, it’s very difficult to see it, when peeping out.

To take a photo of the second birth of a koala becomes my obsession, and after several attempts, we find the right subject.

Now and again, a paw comes out from the belly of the mother, it’s that of the young which is sucking the milk… then enters again.

At last, it appears out with the head, it’s sleeping happily with the little face and the eye out of the marsupium. After two hours of a relative immobility, the mother changes position, and while I fear of having lost the occasion once more, it decides to come out: a “bear-cub” of only 12 cm, with two big chestnut-brown eyes.

I shoot a photograph after the other, and I see, unbelieving, through the view-finder, the young baby kissing the mother.

Photographs which have made the round-the-world tour … a strong moment, really unforgettable for a scientific journalist.

SCIENZA & VITA + NATURA OGGI + TERRE SAUVAGE + TELE LOISIRS + WAPITI + FIGARO MAGAZINE + FEMME ACTUELLE + other magazines – 1987