Family : Hominidae

Text © Dr. Silvia Foti

English translation by Mario Beltramini

Bornean orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus) female with pup in the canopy, the forest vault formed by the tops of the trees © Giuseppe Mazza

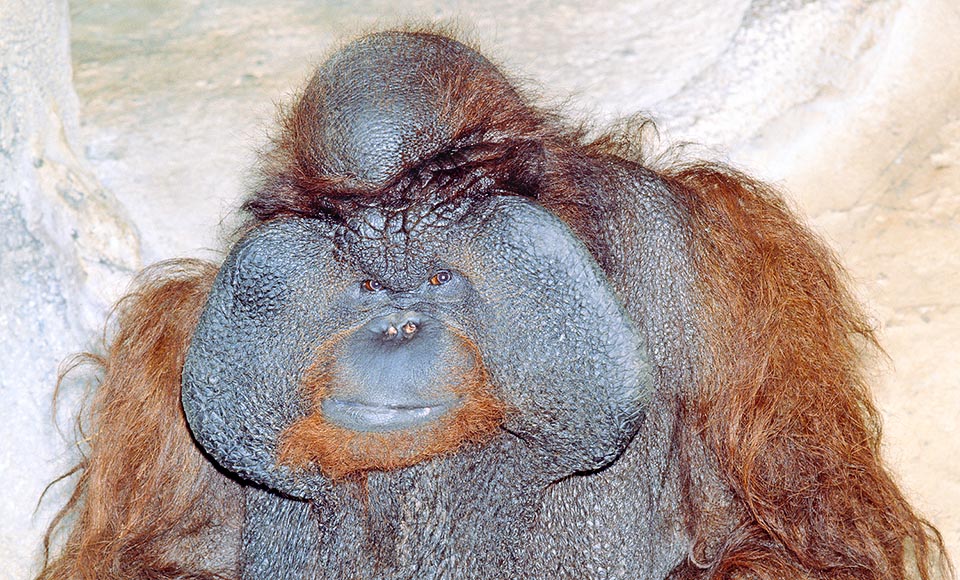

The dominant mature males, called flanged, have a showy facial disk formed by dermic callosities, the flanges, and weigh about twice as the females © Giuseppe Mazza

Moreover the mature flanged have a huge throat sac that allows them to emit a typical long lasting calls, the 1-2 minutes “long-call” , audible even kilometres far away © Giuseppe Mazza

Exactly like the other species of apes, the orangutans show extremely developped cognitive capabilities (they share about the 97% of DNA with the man): they are able to use tools and show characteristic cultura models even in the wild state.

Three subspecies belong to the species Pongo pygmaeus: Pongo pygmaeus pygmaeus (Orangutan of north-western Borneo), Pongo pygmaeus morio (Ornagutan of north-eastern Borneo) and Pongo pygmaeus wurmbii (Central Borneo Orangutan).

However, presently stand some doubts about the belonging of the Central Borneo Orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus wurmbii) to the species Pongo pygmaeus: it seems that it may be closer to Pongo abelii and therefore being a subspecies of the Sumatran Orangutan.

The term Pongo comes from “mpungu”, term used in the Kikongo language (spoken by some populations living in the tropical forests of Angola and of the Democratic Republic of the Congo) to indicate big monkeys of the woods similar to the gorilla (it was rightly thought, erroneously, that the orangutan should have a common origin with the gorilla).

Zoogeography

As the common name states, Pongo pygmaeus is present in Borneo and Sumatra islands, where mainly occupies deciduous and mountain forests, up to the 1500 m of altitude, besides pluvial forests characterized by thick vegetation.

In Borneo, it may be met mainly in the two regions in which Malaysia is divided (Sabah and Sarawak), but is present also in at least three of the four provinces of the Kalimantan region, in Indonesia.

Nevertheless, due to the destruction of its habitat, the distribution of the species presently appears much fragmented. It lives taking advantage from the canopy (the above ground portion of the forests formed by the crowns of the trees) of the primary and secondary forests: its life mainly takes place on the trees, through which it moves looking for food, covering even remarkable distances, and on which usually spends the night, building a couch suspended from the ground.

The young males of Pongo pygmaeus are very similar to the females, that also do have a small throat sac. They can produce flanges from the 15 years of age if not inhibited by the scaring long calls of a dominant male. They are sexually valid, but will not get too heavy and risk to spend all the life as unflanged © Giuseppe Mazza

Morpho-physiology

The Bornean orangutan has a body size varying between 1,2 and 1,4 m of height and between 50 and 100 kg of weight (in the females the height is usually of 1-1,2 m and the weight of 30-50 kg); this renders it in all respects one of the heaviest primates among those presently extant, second only to the two species of gorilla ((Gorilla gorilla and Gorilla beringei), and among the arboreal primates, absolutely the largest one.

Whilst the flanged males do not accept rivals in their territory, that generally overlaps on that of more females, the unflanged are not aggressive at all with the other young males in similars conditions. Rarely they can afford their own small part of forest and so are obliged to wander as immature ceaselessly. If during their sad wandering they meet a female, even if this would prefer a flanged, they get her by force with very acrobatic matings on the trees, thus contributing in the species survival © Giuseppe Mazza

The heaviest ever captive male hitherto known was Andy, an overweight orangutan 13 years old and weighing 204 kg.

The most relevant feature in the whole physiognomy of the orangutans is by sure represented by the very long arms, that may almost be a metre and a half long; they look much longer and stronger than the hindlimbs, but both are prehensile, very useful tools allowing the orangutan to carry on an arboreal life, as an agile brachiator.

The opening of the arms may easily exceed the 2 m of length. Hand and feet are endowed of 4 very tapered fingers and an opposable thumb.

The skull is robust, with very strong jaws and teeth, especially in the adult males.

The body is covered by a reddish coat, shaggy and thick, particularly long in correspondence with the shoulders, where it forms a waterproof garment.

In the male as well as in the female are present throat sacs, utilized for emitting appeals; the male’s ones are more developed.

Always in the male we can see the presence of prominent facial extensions at the height of the cheeks, dermal callosities known as flanges, that form in the adult individual a real facial disc. And it is rightly the development or not of this facial disc that distinguishes the mature individuals in two categories: “flanged” or “unflanged”.

Even if Bornean orangutan is found more often than the Sumatran on the ground, where the tigers are patrolling, these two species are typical arboreal, only members in Asia of the great apes © G. Mazza

The presence of this callosity is usually linked to the age and to the dominance: many males having no flange can develop it gradually as they get older (usually after the 15 years) or while climbing the social hierarchy.

However, it does not mean that this happens.

The males with flanges are fairly aggressive and intolerant towards other males, thing not happening among the unflanged males; both typologies of male, however, can contribute to the reproductivity of a social group, generating progeny.

In respect to the Sumatran orangutan, the Bornean one has a darker more massive coat, bigger weight, facial discs more pronounced, covered by bristly hairs, and throat sacs more developed.

Ecology-Habitat

The orangutan nourishes mainly of fruits: about the 60% of its diet is based on the consumption of figs, litchis, rambutans, breadfruits, mangoes and durians.

The availability of such fruits is not constant during the year, and it is rightly for this reason that the young learn very early from their mothers how to select the right trees and to remember the periods when they produce the fruits.

Besides the fruits, its diet includes also berries, buds, leaves, flowers, roots, bark, honey, insects, small vertebrates (like the Slow loris) and eggs, totalling more than 400 foods.

This is why the predilection for such a vast range of fruits renders the orangutan an extraordinary disseminator of seeds, especially for those plants whose seeds have a quite remarkable size and that consequently cannot be eaten by small animals. The importance of this rôle is evidenced by the nickname with which these apes are called: “gardeners of the forest”.

Among the primates Pongo pygmaeus is second for weight only to the gorillas. In nature the males can weigh 50-100 kg with 1,2-1,4 m of height, the females 30-50 kg per 1-12 m. When captive often risk obesity. Obliged to sedentary life, as happens also for men, a 13 years old male has sadly reached the 204 kg © Giuseppe Mazza

The peculiar feature of the species is in the very long arms that may reach a meter and a half, whilst the lower limbs are slightly shorter. The four hands are prehensile, with long fingers and opposable thumb: ideal in the tropical forest for a canopy brachiator's life © Giuseppe Mazza

An enough long and gnarled branch may become an extension of the arm in order to be able to scratch the back, as well the leaves may be used for peeling spiny fruits or for wiping away the droppings.

In some cases, the orangutans can swallow small quantities of land, in order to get a sufficient dose of minerals able to neutralize the toxins and the acids they constantly assume nourishing of fruits and grasses.

Usually the orangutans consume a very abundant meal in the morning, activity that takes up to three hours.

They do not have predators, but the men, as conversely happens for the Sumatran orangutan, who must constantly watch its back from the Sumatran tiger (Panthera tigris sumatrae).

However, the Bornean orangutan must pay attention when the not negligible Sunda clouded leopard (Neofelis diardi), goes around as it is strong enough to take down from a tree a naive puppy.

The Bornean orangutans carry on a rather solitary life; they can interact with other similars, at times, but always for short periods of time.

Usually they are always more solitary than the Sumatran orangutans; two or three individuals may get in touch in the case their territories do overlap, but always for very limited periods of time.

Although being arboricolous animals, the Borneo orangutans move on the ground more than their Sumatran cousins.

This is due, most probably, to the absence of major predators that can put in danger the movements on the ground of the Bornean orangutan.

Ethology-Reproductive Biology

The females mature sexually between the 6 and the 11 years, an age that can vary much also on the base of the quantity of body fat they have available.

The estrus cycle lasts 22 to 30 days, and the menopause occurs when about 48 years old. The pregnancy lasts about 245 days, after which is usually delivered only one pup.

When moving the Bornean orangutans use various locomotion methods: whilst the young prefer pass from a tree to another, exploiting the their long and strong arms, the older individuals move usually walking on all four limbs or even, for short strecthes on almost horizontal trunks, prudently, in erect position © Giuseppe Mazza

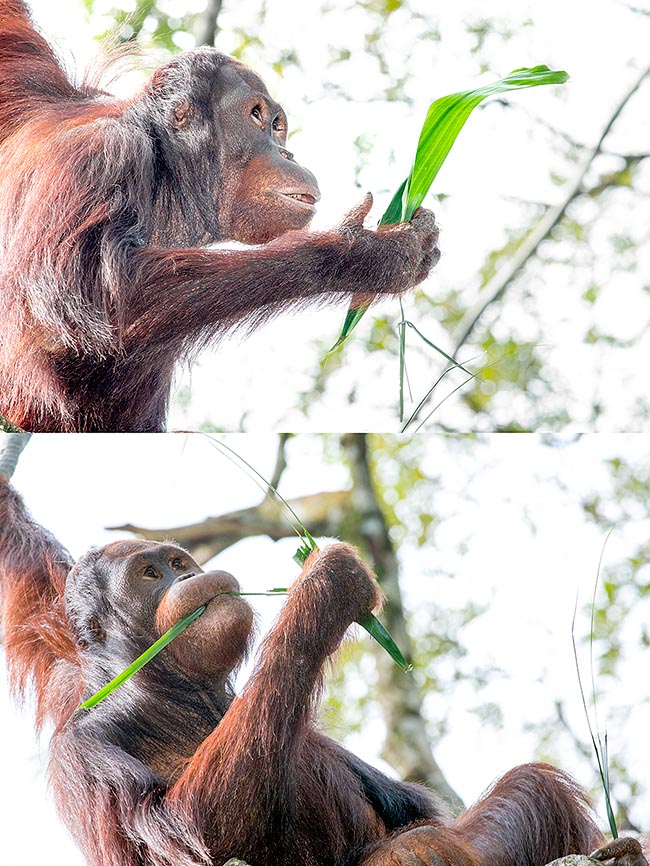

They mainly eat fruits: about 60% of their diet is based on consumption of figs, litchis, rambutans, breadfruits, mangoes and durians. But also vegetables, as in this case, buds, leaves, flowers, roots, bark, honey, insects, small vertebrates and eggs, for a total of more than 400 aliments © Giuseppe Mazza

This change in the mother’s behaviour will mark also the moment when the sons will separate from the mother, establishing a territory close to the mother’s one.

Very often a flanged male has a territory including also that of numerous females, with whom it mates; the unflanged males, on the contrary, rarely are able to get their own territory and are obliged to wander around; when, during their wandering, they meet a female usually they oblige her to couple, as these prefer by far to mate with the flanged males.

Mating occurs in a quite acrobatic manner: both partners let themselves dangling from the trees, clinging with their powerful arms, facing each other.

The Bornean orangutans do not have a reproductive season, but the females show a greater ovarian activity during the periods of food abundance.

Whilst the females invest a lot of energy caring the progeny, breeding it till adolescence has come, the males, opting for a solitary lifestyle, do not have almost any contact with their own sons.

They are diurnal animals and spend most of time on the trees.

The females move in small groups, with their progeny following, whilst the adult males are solitary also during their movements.

However, during the period when the fructification of a group of trees takes place, temporary groups of 6 or more individuals take form; rightly the seasonality of the fruits they eat determines the daily and seasonal movements.

The Pongo pygmaeus mainly eat fruits: about 60% of their diet is based on consumption of figs, litchis, rambutans, breadfruits, mangoes and durians. But also vegetables, as in this case, buds, leaves, flowers, roots, bark, honey, insects, small vertebrates and eggs, for a total of more than 400 aliments © Giuseppe Mazza

The leaves enter regurlarly the Bornean orangutan diet and they are called “gardeners of the forest” because unlike the small animals they have strength for moving and dispersing even big seeds © Giuseppe Mazza

They cannot swim: this renders rivers and other water surfaces insurmountable limits, putting barriers to their dispersion.

The Bornean orangutans, rightly because not very social animals compared to other species of big apes, do not have an ample variety of vocalizations.

The main is the one of long duration, a 1-2 minutes call emitted by the flanged males and audible even at various kilometres far away.

The meaning of this vocalization is that of informing other males of the presence of the one emitting it, important information mainly for the unflanged individuals, who usually retreat away quickly, but also to inform the sexually receptive females.

Some studies suggest that these calls should be those “inhibiting” the development of the unflanged males: to hear a long-call coming from a strong-flanged male should trigger the production of stress hormones, with the result that in the more immature males the development should interrupt. Another call produced by the Bornean orangutan is the “fast” one, usually manifested during the confrontations between males, whilst when a danger is perceived; these apes emit real and true screams.

Happiness is also to taste a leaf on top of the preferred tree © Giuseppe Mazza

The Bornean orangutan has an average life from 35 to 40 years in the wild; in captivity, conversely, the same may reach the 60 years of age.

The orangutan is an animal able to have very good relations with the man. It is able to learn from the man’s behavior and is able to do things similar to him (to put nails, to cut a piece of wood with the saw…) even only by observing him.

Only big primate nowadays present outside the African continent.

In Borneo is present a center for the protection of the orangutans. The mascot of this center, already since the late seventies, is a female orangutan to whom have been taught more than thirty signs of the alphabet for the deaf and in such way it is able to converse with the human beings.

The center hosts orangutan infants left orphans due to the pitiless hunting done against the mothers rightly for seizing the pups. After having been treated and once grown, the orangutans are released in the wild inside protected areas.

Conservation

The Bornean orangutan is presently classified as Endangered (EN) inside the Red List of IUCN and is inserted into the Appendix I of CITES.

The Bornean orangutan is really in danger. The present number of orangutans is estimated being 14% less than what was till short time ago (from about 10000 years to the mid-twentieth century) and this dizzying decline has been registered especially during the last decades due to the human activities. Nowadays the Bornean orangutan distribution appears amply fragmented; it seems absent or anyway very uncommon in the south-eastern part of the island, as well as in the forests around the Rejang River and in the Padas River.

The discovery of crispy buds is a feast time. Pups stay close to the mother for 6 years, time for growing and learning where, how and when to nourish © Giuseppe Mazza

Pregnancy lasts about 245 days, and usually only one pup is delivered. The newborns are milked every 3-4 hours, and start with solid food, chewed by mum, around the 4 months of age © Giuseppe Mazza

Moreover, due to the long interval that elapses between one birth and another one (even 6-8 years), the orangutans have become particularly vulnerable to all above factors.

It seems, then, that one third of the Bornean orangutans has disappeared because of the numerous fires that have invested a large part of the Indonesian forests in 1997 and in 1998.

Furthermore, the orangutans living in the zones used for plantations of oil palm and other areas used by the man may easily be preys of catches finalized to feed the pet trade channel.

The Bornean orangutan is protected by the law in Malaysia as well as in Indonesia; however, despite some populations are located inside of protected areas, the illegal logging even inside these areas remains a substantial threat for the survival of this species.

With the aim of ensuring the conservation of the species, among the various actions done for the safeguard of the orangutan stands the active involvement of the local populations.

Despite this, analizing, one by one, all the threats concerning the poor, helpless orangutans, appears clear how all what is being done presently is not yet sufficient to guarantee the survival of these apes.

Loss of habitat: consequence of the distruction of ample areas of tropical forest due to the conversion to cultivation of Elaeis guineensis, that is the oil palm, but also of acacia, rice, coconut palms, subsistence cultivations, etc. Between 1985 and 1997 it has been estimated the loss of about 15,5 millions of hectares of forest in the island of Sumatra and in the region of Kalimantan (the Indonesian part of Borneo).

The continuous demand of palm oil used in the food, cosmetic and mechanical industries, during the last decades has resulted in a dramatic increase of the area dedicated to such cultivations (from 2.000 sq.km to 27.000 sq.km in less than 20 years).

Fires: during the last decades the island of Borneo has been hit several times by the climatic event of El Niño, bringing with him serious droughts and forest fires. The 90% of the Kutai National Park has been lost due to massive fires happened in 1983 and in 1998 and its populations of orangutans has reduced from about 4000 individuals (in 1970) to less than 500. Moreover, the most recent wave of drought in Kalimantan, dated 2006, is thought having exterminated various hundreds of ornagutans in only six months.

Exploiting of the habitats and unlawful logging: the orangutans are a species with capacity to adapt also to altered ambiental conditions, as they are able to survive in forests exploited for the wood, provided that the timber harvest takes place in the respect of sustainable practices. Unluckily, this does not appear to be a common scenario: the adoption of surely more conventional practices, characterized by their high ambiental impact, is getting dramatic implications on the already compromised populations of orangutans.

Look how good I am! I have climbed like mum the big tree … I reached the top © Giuseppe Mazza

Fragmentation of the habitat: it stands at the basis of populations that count a too small number of individuals; in the case when the number of membres is around fifty it seems that such populations are destined to extinct in about 100 years; rightly the fragmentation of the habitat reduces the dimensions of these populations and renders them more vulnerable with regard to genetic drifts and ambiental factors.

The Bornean orangutan has an average life of 35 to 40 years in the wild; in captivity, conversely, can reach the 60 years © Giuseppe Mazza

Hunting: in some parts of the island, hunt represents the threat of larger entity and is the direct responsible of the local extinction. The causes of a so high hunting pressure stand in the use of these animals for the meat, in the use of parts of their body for the traditional medicine, or in the catching of pups for the pet-trade and for mitigating the impact these animals do have on the cultivations.

It’s an animal able to relate very well with man. It learns, observing, to use hammer and saw. In Borneo stands a centre for orangutans protection and a female has learnt to use 30 signs of deaf humans alphabet in way to converse with the staff. In nature live about 6900 individuals in the Sabangau National Park, but the species is endangered due to habitat loss linked to deforestation, mainly for palm oil cultivation, fragmentation of the sites where they lived since centuries, the fires, the hunting linked to old beliefs, that persists despite prohibitions, and the sad, illegal taking of pups for the “pet-trade” Globally in the wild there are only 54 500 individuals © Giuseppe Mazza

However, despite the present scenario being decidedly alarming and does not bode anything good for the future of these magnificent frugivorous apes, the Bornean orangutan is presently more common than the Sumatran one, with about 54.500 individuals of the first versus the 6600 of the second, in the wild. At this point, the question is only one: for how many more years we shall be able to admire, appreciate and study this species, before the man successfully realizes his goal of destroying it, manipulated and blinded by the “god of money” that dominates his (in)civility?

→ For general notions about Primates please click here.

→ To appreciate the biodiversity within the PRIMATES please click here.