Gorgeous flowers blossom from flames. They only reproduce when a fire frees the ground from the thick layer of leaves that stifle the seeds. The gorgeous flowers often have an iridescent look. Thousands of varieties in the common structure of the flower. How to cultivate them.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

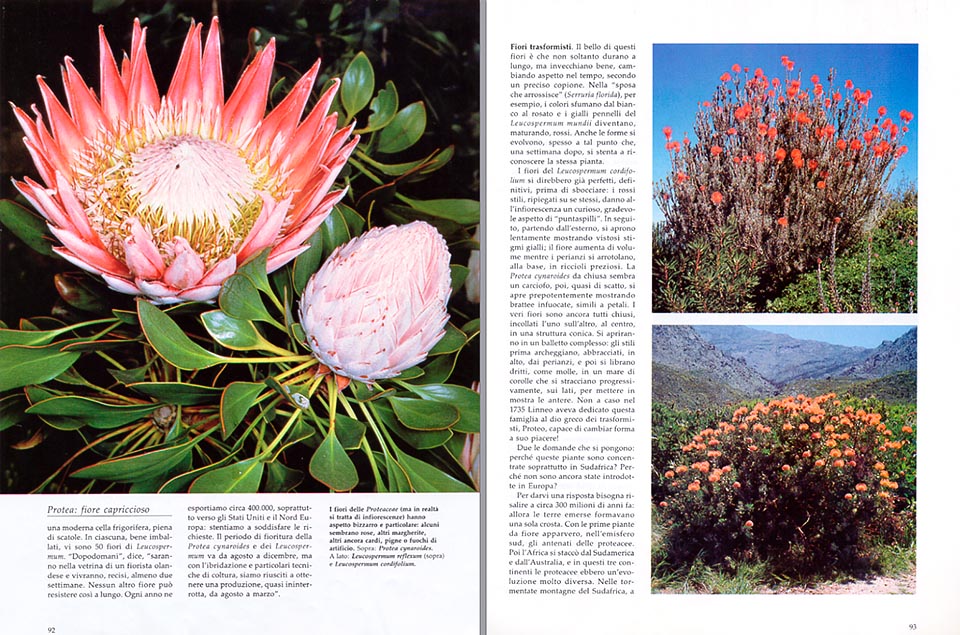

The roses, the carnations, the chrysanthemums, and many other cut flowers, will be, gradually, replaced, by the year 2000, by a new group of plants: the proteaceae.

Even if today it may look impossible, it will be a normal thing to give as present bouquets of variegated Leucospermum, Mimetes or Leucadendron, and the showy King Protea (Protea cynaroides), will enter commonly in the houses.

The Prof. John Patrick Rourke, distinguished taxonomist of the botanical garden of Kirstenbosch, in South Africa, author of the most prestigious book about the proteas, as no doubts about.

It is very exciting, he explains to me, to study a group of plants where do exist, still now, species not yet described, (he has already classified 15 of them), and to live, in our times, personally, the same experience of domestication the men have done, thousands of years ago, for instance, with the roses and the olive-trees.

It’s a recent adventure, of the last 15 years maximum: before we were limiting ourselves to cultivate some botanical form, but now the cut flower industry and the increasing demand of proteaceae for the gardens, has induced to the selection of cultivars with longer flowering, more resistant, with always more beautiful and showy flowers. They look for spectacular hybrids also with the Australian species.

Mr. Steenkamp, manager of the PROTEA HEIGHTS of Stellenbosch, a centre of commercialization of these plants, shows me, proudly, a modern refrigerant cell, full of boxes. In each one of them, there are fifty flowers of Leucospermum, well packed.

The day after tomorrow, he tells me, they will be in the shop of a Dutch florist, and will last, cut, for at least two weeks. No other flower can do the same. Every year, we export about 400.000 of them, mainly to USA and North Europe, and we have difficulties in satisfying all requests.

The normal period of flowering of the Leucospermum and of the Protea cynaroides goes from August to December, but, with the hybridization and particular techniques of cultivation, we can get a production, almost uninterrupted, from August to March.

The best of these flowers is not only that they last long time, but they age well, changing of aspect in the time, following a definite script.

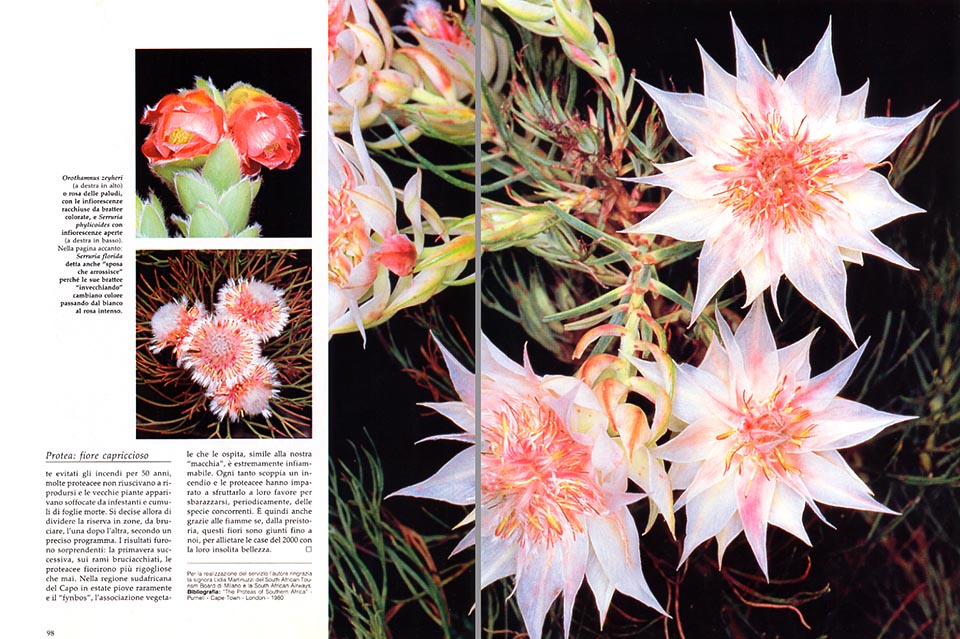

In the Blushing Bride (Serruria florida), for instance, the colours gradate from the white to the pink, and the yellow brushes of the Leucospermum mundii, become, while ripening, red.

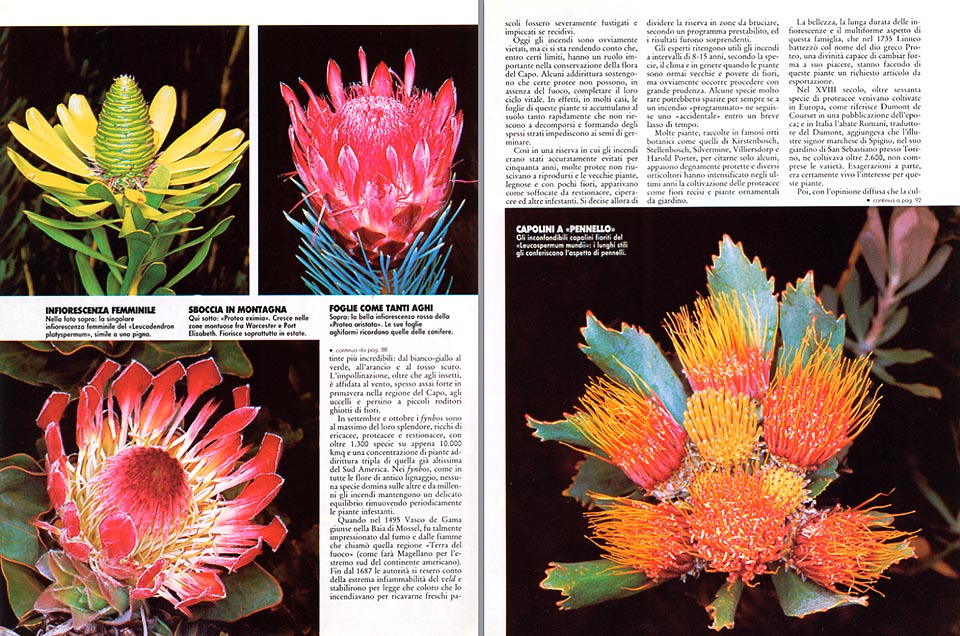

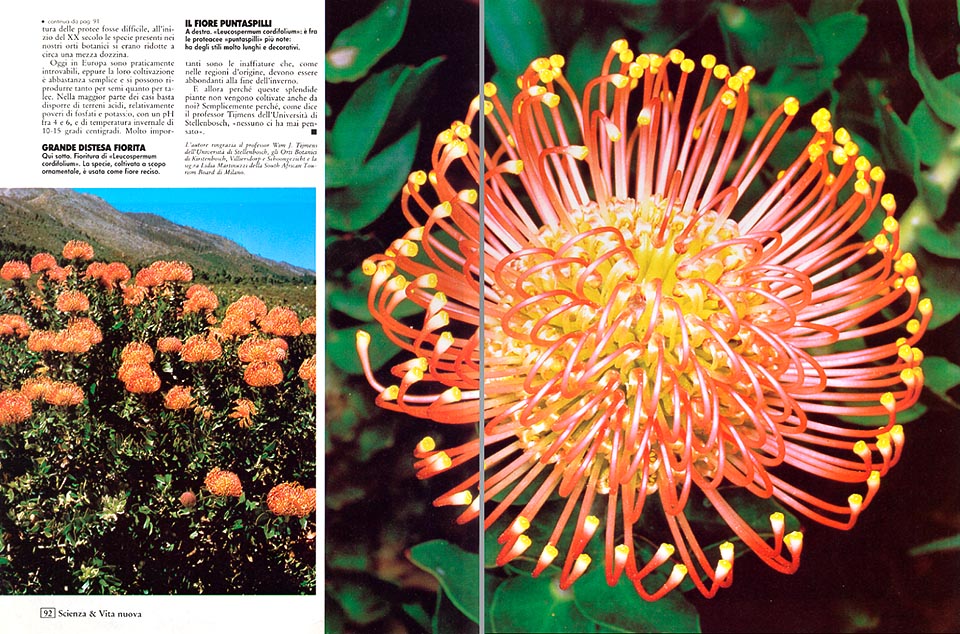

Also the forms evolve, often so much that, after one week, we have difficulties in recognizing the same plant. The flowers of the Leucospermum cordifolium could already be considered perfect, final, before blossoming: the red tyles, bent on themselves, give to the inflorescence an odd, pleasant look of “pincushion”. Then, starting from the outside, they open slowly, showing evident yellow stigmata, and the flower increases its volume while the perianths roll up, at the base, in precious curls.

The Proeta cynaroides, when closed, looks like an artichoke, then opens, overbearingly, almost suddenly, displaying some blazing bracts, similar to petals. The real flowers, are still all closed, stuck one on the other, at the centre, in a cone-shaped structure. They will part only the next days, opening in a complex ballet where the styles, at the beginning, are bowing, embraced, on the top, by the perianths, and then soar, straight, like springs, in a crowd of corollas which progressively tear to pieces, on the sides, for showing up the anthers.

It is not by chance that in 1735, Linnaeus had dedicated this family to the Greek god of the quick-change artists, Proteus, capable to change form at his own will!

But why these plants have concentrated mainly in South Africa and why they have not yet been introduced in Europe?

For an answer we have to go back to about 300.000.000 years ago, when the emerged lands were still forming one crust. The ancestors of the proteas appeared in the southern hemisphere, along with the first flower plants.

Then Africa parted from South America and Australia, and, in these three continents, the proteaceae had a very different evolution. In the tormented mountains of South Africa, close by two oceans, between the desert and the sea, formed an infinity of micro climates and ecological recesses, well distinct, which caused an unprecedented botanical diversification.

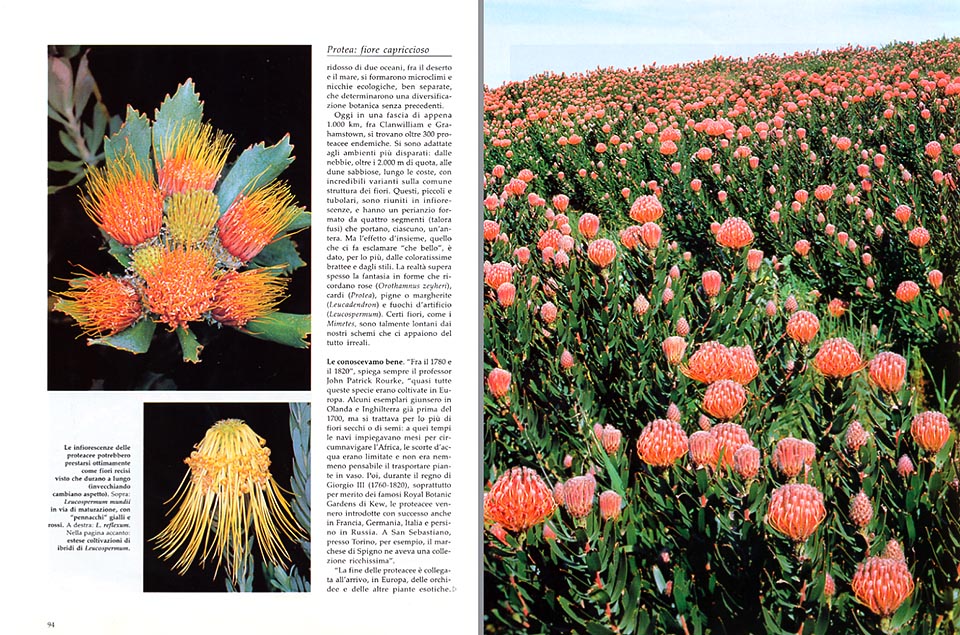

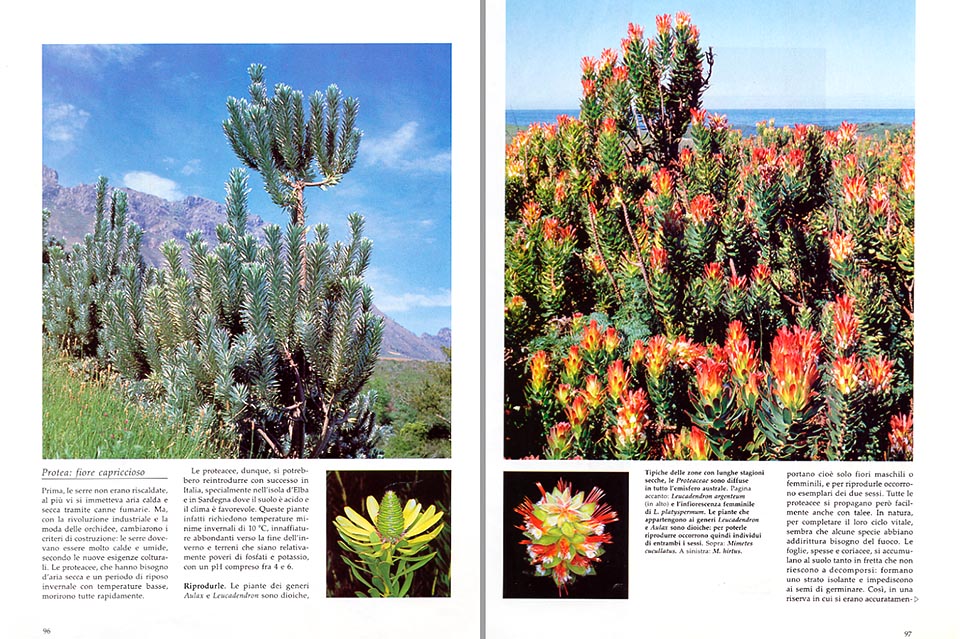

No wonder, then, if now, in a stripe of only 1.000 Km, between Clanwilliam and Grahamstown, we find more than 300 endemic protaceae. They have adapted to the most dissimilar habitats, from the fogs, over the 2.000 metres of altitude, to the sandy dunes, along the coasts, with incredible variants on the common structure of the flower. These ones, small and tubular, are united in inflorescences, and have a perianth formed by four segments (sometimes blended), which carry, each one, an anther.

But the effect of the whole, which pushes us to exclaim “beautiful!”, is given, mostly, by the very coloured bracts and the styles. The reality overcomes often the fantasy, in forms which recall the roses (Orothamnus zeyheri), thistles (Protea), cone-pines or daisies (Leucadendron), and fireworks (Leucospermum).

Certain flowers, like the Mimetes, are so much distant from our schemes, that they seem to us absolutely unreal.

Between 1780 and 1820, Prof. John Patrick Rourke explains to me, almost all these species were cultivated in Europe. Some specimen reached Holland and England even before 1700, but tjey were mostly dry flowers or seeds: in those times the vessels needed months to circumnavigate Africa, water reserves were limited, and it was absolutely unthinkable to carry plants in pot.

Then, under the rule of Georges III (1760-1820), mainly thanks to the famous Royal Botanic Gardens of Kew, the proteaceae were introduced, with success, also in France, Germany, Italy, and even, in Russia. At San Sebastiano, close to Turin, for instance, the Marquis of Spigno had a very rich collection.

But then I ask, curious, what has happened to all these plants.

The end of the proteas, he continues, is connected to the arrival in Europe of the orchids and the other exotic plants.

Before, the greenhouses were not heated, at the most, they introduced some warm and dry air through flues. Then, with the industrial revolution, and the fashion of the orchids, they changed the building criteria: the greenhouses, rich of radiators, had to be very hot and humid, as per the new cultivation requirements.

The proteaceae which need dry air and a resting winter period, with low temperatures, passed all away quickly.

Therefore, I conclude, they might be reintroduced, with success, in Italy.

Sure, especially in the Elba Island and in Sardinia, where the soil is acid and the climate suitable. They need, in fact, lowest minimum temperatures of 10 °C, abundant watering around the end of winter, and grounds somewhat poor in phosphates and potassium, with a pH between 4 and 6. In Milan, a greenhouse not much heated, rather dry, and a soil acidified with quartz sand, might be quite suitable.

The plants of the genera Aulax and Leucadendron are dioicous, that is, they carry only masculine or feminine flowers, and for reproducing them, we should then to give hospitality to specimen of both sexes.

All proteaceae propagate, nevertheless, easily, also by cutting. In the wild, for completing their vital cycle, it seems that some species need even the fire. The leaves, thick and leathery, accumulate, in fact, so fast on the ground, that they do not reach the decomposition: they form a thick insulating stratum and do not allow the seeds to germinate.

So, in a reserve where they had accurately avoided fires for 50 years, many proteas could not reproduce, and the old plants, woody and with scanty flowers, were choked by pests and heaps of dead leaves.

Then, they decided to split the are in zones, to be burnt, one after the other, following a definite programme.

The outcome was surprising: the next spring, on the burnt branches, the proteas blossomed from the ashes, luxuriant, as they had never been.

In the region of the Cape, in summer, it seldom rains, and the “fynbos”, the vegetable association which gives hospitality to them, similar to out “thicket”, is extremely inflammable. Every now and then, a fire breaks up, and during millennia of evolution, the proteaceae have learnt how to take advantage of it, and to get rid, periodically, of the competing species.

It is, therefore, thanks to the flames, if, from prehistory, these flowers have come so numerous to us, for cheering up the houses of the year 2000, with their unusual beauty.

SCIENZA & VITA + GARDENIA – 1987