Family : Sphenodontidae

Text © Prof. Giorgio Venturini

English translation by Mario Beltramini

Endemic to New Zealand, the Tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus) looks like a big lizard, but actually, for many, is a “living fossil” © Giuseppe Mazza

The Sphenodon punctatus, or Tuatara in the Maori language, is the only existing member of the Rhynchocephalians, one of the four orders of reptilians living nowadays (or better five if we include among the reptilians also the birds after the opinion of many modern scholars). The order of the Rhynchocephalians (Rhynchocephalia) from the Greek (ρυγχος) “rynkos” = beak and (κεφαλε) “kefale” = head (hence with the head shaped like a beak), that included several families occupying different habitats, had its maximum development during the Mesozoic period, therefore at the same time as the dinosaurs, and has practically extinguished about 60 million of years ago.

Around 100 million of years ago the old continent Gondwana was fragmenting and New Zealand, only present habitat of the Tuatara, was separating from Australia. In this way probably some ancestors of the Sphenodonts remained isolated in a land where were absent the terrestrial mammals and where were missing also other important predators and competitors, unique fossil of terrestrial mammal, apart the bats, is the small and archaic mammal of Saint Bathans, disappeared in the Miocene. This is probably the cause that allowed the survival of the Tuatara until our days without meeting substantial changes, whilst in the rest of the world the rhynchocephalians were facing the extinction. An analogous situation has occurred for other animals endemic to New Zealand, in particular for the various species of birds unable to fly such as the Kiwis (Apteryx), the Weka (Gallirallus australis), the Kakapo (Strigops habroptila) or the Moa (Dinornis) these last extinct in historical times.

It has a third eye on the head, called pineal, facing the sky © Giuseppe Mazza

In New Zealand they have found fossil remains of rhynchocephalians similar to the sphenodont dating back to the late Pleistocene (about 30 thousand years) and the Miocene (19-16 milioni di anni), in agreement with the hypothesis that the ancestors of the Tuatara were present in the lands that, separating from the continental mass of the Gondwana have originated the New Zealand.

Conversely if, as suggest some recent studies, New Zealand has been completely submerged around 25 million of years ago, we have to admit that some ancestral sphenodonts, transported adrift on the ocean starting from an unknown origin, have colonized in the Miocene the newly formed islands.

This reptilian endemic to New Zealand, morphologically looking like a big lizard, is by many considered as a living fossil, that is as the membre of a species of very old origins that has kept unchanged for many millions of years.

However, this point of view is not shared by some scholars on the base of the observation that many of morphological characteristics of the present Tuatara are not the same as those of the fossil forms and are conversely the result of specializations occurred during countless years. Moreover, the analyses of the mithocondrial genome in this species show a speed of molecular evolution bigger than that of many other vertebrates.

The term “sphenodon” comes from the Greek (σφήν) “sphen” = wedge and (ὀδούς) “odous” = tooth, hence wedge-shaped teeth. “Punctatus” in Latin means speckled. Tuatara in the Maori language of the natives to New Zealand means “spines on the back”. In the past were recognized two different species of sphenodonts: the Sphenodon punctatus and the Spenodon guntheri, present in the island Borthes located in the Cook Strait, characterized by smaller size and by a different pigmentation. Nowadays one only species is recognized with two subspecies: Sphenodon punctatus punctatus and Sphenodon punctatus guntheri (The name guntheri is honoured to the herpetologist Albert Günther). Before men, that is the Maori, did reach New Zealand, probably between the 1280 and the 1300 A.D., the Tuatara lived the dry land of both two main islands, that of the North as well as that of the South, and also minor islands, as evidenced by sub-fossils findings.

The Maori took with them the Polynesian dog (kurī in their language) that was utilized as source of food and of fur, used for making the prized cloak Kahu kurī and the Polynesian rat (Rattus exulans o kiore) which they fed. These animals, the first mammals for New Zealand, preyed the Tuatara, devouring their eggs and destroying their nests; the same Maori often hunted them to feed on them and consequently, at the arrival of the Europeans the sphenodonts had practically disappeared from the mainland, remaining confined in several small islands off the coasts. With the Europeans did arrive their domestic animals and especially two new species of rats, the Black rat or House rat (Rattus rattus) and the Common rat or Brown rat (Rattus norvegicus) that invaded also many minor islands of New Zealand causing a new very serious decrease of the population of Tuatara.

Covered by a transparent scale, then pigmented, is visible only when young. It does not allow the vision but informs about the colour of the light or the position of sun in cloudy days. It stimulates the pineal gland for the production of hormones and neurotransmitters regulating waking, the sleep, the thermoregulation and the reproductive activity © Southland Museum & Art Gallery, Invercargill

Nowadays the sphenodont is present in numerous islands off the north-eastern coast of the North Island and some islands of the Cook Strait, that separates the North island from the South one. It is estimated that presently the total population of Tuataras amounts to about 60.000-100.000 specimens, of which about 600 of the subspecies guntheri.

The most important population is that of Stephens Island (Takapourewa in the Maori language), in the Strait of Cook, amounting to about 30.000 specimens. New Zealand government has engaged in various activities tending to increase the number of the sphenodonts and to introduce them in the two main islands. These activities foresee in first lieu the elimination of the rats as, preying the nests, form the main obstacle to the reproduction of the Tuataras.

The introduction of some specimens of Tuatara in the mainland, in the Karori naturalistic Sanctuary, close to Wellington, has met an important success with the first birth of new specimens in 2009. Moreover, several centres in the North Island as well as in the South one, breed the Tuatara in captivity for research purposes and for reintroducing them in suitable habitats. Historically among these centres the first has been the Southland Museum and Art Gallery of Invercargill, famous for hosting the old Henry, a Tuatara that in 2009, at the probable age of about 110 years, coupled with the octogenarian Mildred, has generated about ten children. It is to be emphasized that Henry was a veteran of the surgical removal of a cloacal cancer and the success of the operation has rendered possible the mating.

Recently the New Zealand government has announced a plan for the eradication of the invasive species that ravage the extremely particular ecosystem of this country. In particular they aim to eliminate all rats, the mustelids and the possums by 2050, with the purpose to allow the native species, such as the Tuatara, to reconquer their original habitats. Of particular interest is the problem of the Possums: these marsupials (Trichosurus vulpecula), that have bee imported from Australia around the 1837 mainly for the production of fur, have soon revealed themselves a real calamity, going to meet an uncontrolled multiplication, up to reach the about 70 million of specimens, thanks to the absence of predators and competitors.

The measures adopted so far have been able to reduce the population, that however still amounts to some tens of million and that causes very heavy damage as vector of zoonosis, impoverishment of the vegetation and predation of the nests of the autochtonous species.

The wedgy teeth have given the name to the genus Sphenodon. Only case in the world of the vertebrates, the upper jaw has two rows of teeth, whilst the lower one, perfectly closing and interlocking, displays one row only © G. Mazza

Morphology

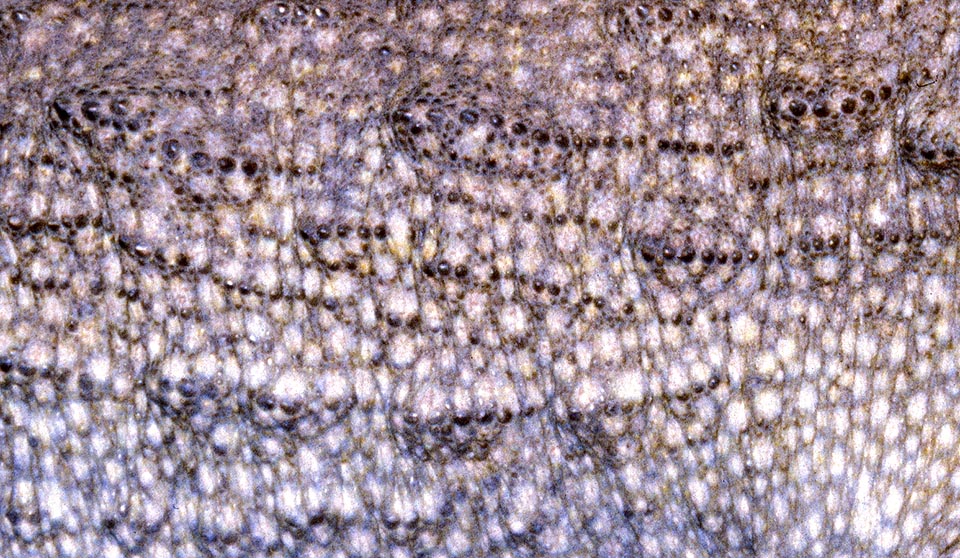

The Tuatara has the general look of a big lizard with a maximum length of 70-80 cm and a weight that may exceed the 1200 g, with the males generally bigger than the females. The colour that goes from the brown-greenish to the reddish to the grey, the colouration can change during the life of a specimen and every year the skin is changed.

On the back is present a spiny crest, more marked in the males, supported by cutaneous folds. The crest may become erect during the courting or the fights between males. Its anatomy displays remarkable peculiarities, some of which evidence its primitiveness. The teeth, shaped like wedges, are welded to the bones of the jaws, that for this reason appear serrated, and have a disposition unique among all vertebrates: in the upper dental arch are present two rows of teeth whilst in the lower one is present only one row that when it opens the mouth adapts perfectly between the two upper rows.

This disposition, not found in any other reptilian, together with the fact that the mandible while chewing can move back and forward, allows the animal to grind even very hard preys, chitinous or containing bones, before swallowing them down. These movements allow also a self-sharpening of the teeth. Seen that the in the Tuatara the teeth are not changed during the whole life, and meet a continuous damage, the old animals with the dental arches almost completely smooth, can nourish only of soft foods like worms and larvae or snails.

The skeleton displays various peculiarities: in the Tuatara the skull has primitive characteristics: it is therefore of the dipsid type that presents evident the two openings (temporal fenestra) typical to the oldest fossil reptilians. The vertebraes show the front face as well as the back one concave (they are defined amphychoelous, that means, with double cavity), such as those of the fishes, unlike those of the other reptilians that display one concavity. In the space between two adjacent vertebrae, delimited by the two concavities, is present a showy remnant of the dorsal tail, that is of the structure of dorsal support that precedes evolutionarily the spinal column and that in the other vertebrates is present only in the embryos and in the adults remains only as small remnants (in the man they are the pulpy nuclei of the invertebral discs).

The livery of the Tuatara is usually brown-greenish, mimetic with the environment, but the tonality changes with the age and in the reproductive time gets darker © Giuseppe Mazza

Also the ribs are peculiar, as showing large uncinate processes, that is protrusions that, heading backwards, tend to connect every rib to the adjacent one. Like in the crocodiles and in many dinosaurs are also present and well developped the ventral ribs, that is the “gastralia”, a group of bones shaped like rib that create a sort of abdominal cage that protects and supports the bowels. Among the numerous anatomical peculiarities of the sphenodont, it is worthy to remind again the primitiveness of the skull, of dipsid type, that maintains many of the original characteristics of the first amniotes.

As it happens also for most of the lizards the Tuatara is capable of self-amputating of the tail in case of aggression (autotomy). In this way the tail is abandoned to the predator, this distracts it continuing to writhe, while the Tuatara can escape. From the stump regenerates a new tail that however differs from the original tail for the colour and for some anatomical properties.

Sensory organs

The few studies done on the sensorial apparatus suggest that the sight organ plays a primary rôle in the social behaviour as well as in the reproductive one and also in the predation, even if it has been noted that these animals bite shapes of cotton that have been rubbed on preys, which proves that also the sense of smell or generally the chemoreception plays a rôle in the feeding.

The focussing of the lateral eyes is independent and shine in the light of the night like those of the cats © Paddy Ryan

The eyes, that can be focused independently one of each other, are provided of cones for the day vision and of rod cells of the night one. Like in other nocturnal vetebrates the vision in conditions of poor lighting is facilitated by the presence of a reflecting glossy carpet placed behind the retina: in this way the light rays that have not been intercepted by the photoreceptors are reflected forward and can cross again the retina thus doubling the sensitivity (in the diurnal animals, like the man, in lieu of a glossy reflecting carpet is present a black carpet that absorbs the light rays and prevents their reflection, reducing the sensitivity but increasing the definition). The presence of the reflecting glossy carpet in the nocturnal animals explains us the reason why the eyes of the cat shine in the dark when hit by a light beam: the beam is reflected by the glossy carpet like if by a mirror.

The ear is very primitive: the eardrum is absent and the middle ear is filled up by a loose tissue, essentially adipose. The auditory apparatus of the Tuatara is able to perceive sounds of frequencies between the 100 and the 800 Hz, with a maximum sensitivity of 40 dB to 200 Hz. It is consequently in condition to perceive sounds like those of the human voice at levels comparable to those of a normal conversation but would have difficulty with a soprano female voice. Like in many other vertebrates the sense of smell is localized as well as in the nasal mucosa also in the vomeronasal organ or Jacobson’s organ, placed in the vault of the palate. In the Tuatara as well as in the turtles this organ has the function of perceiving the odours of the food contained in the mouth.

The day, when they do not need to thermoregulate in the sun, the adults rest in dens dug in the subsoil, at times taken to the sea-birds with whom they coexist, and go out hunting during the night. Thanks to the eyes rich of rod cells and with a glossy carpet behind the retina they surprise the preys in the darkness © Giuseppe Mazza

One of the most interesting aspects of the Tuatara anatomy is however the remarkable development of the third eye, called parietal eye or pineal eye.

The pineal eye is a photosensitive structure, present in some vertebrates such as lampreys, some fishes, amphibians and some reptilians, localized in the upper region of the brain called epithalamus. Whilst in many animals the third eye is more reduced and simplified, in the Tuatara it maintains a structure almost identical to that of the two lateral eyes. In the newborn the parietal eye is covered by a transparent scale, whilst in the adult the cover becomes more opaque and pigmented but in any case allows the passage of the light rays.

The parietal eye externally is quite similar to the two normal eyes of the vertebrates (lateral eyes), with its globose shape, covered by one cornea and one crystalline, both transparent, filled up by a gelatinous substance (vitreous humour) and with the bottom covered by a retina, containing the photoreceptors, that originates a nerve, called parietal, equivalent to the optic nerve. Despite the remarkable similarity it shows however quite important differences, that is necessary to describe. The retina of the lateral eyes of the vertebrates is formed by several layers of nervous cells and is of inverted type, that is the layer of the photoreceptors is placed under all other layers. In this way the light rays must pass through all the retinal layers in order to reach the photosensitive portions of the photoreceptors (cones and rod cells).

Conversely the young are active in the day, when the adults sleep, because unluckily are not rare the cases of cannibalism © Paddy Ryan

In turn, the retina lays on a pigmented layer that covers the bottom of the eye (pigmented retina). Conversely, the retina of the parietal eye is not inverted and therefore the photosensitive portions of the photoreceptors are turned towards the light rays that come from the lens, but with the interposition of the pigmented layer that therefore is not placed under the retina but over it.

For understanding the structure of the lateral eyes of the vertebrates and the differences with the parietal eye we must understand their embryonic development.

The central nervous system originates in the embryo like a tube with a relatively thin wall closed in front. During the development a series of swellings and thickenings will form the different portions of the brain, whilst the internal cavity represents the cerebral ventricles. The lateral eyes originate like two protuberances shaped like a vesicle (eye vesicles) that generate from the lateral wall of one of the portions of the encephalon, called diencephalon, whilst the parietal eye originates from a vesicle that is born from the dorsal portion of the diencephalon, the epithalamus, from which takes form also the epiphysis. Hence the eyes belong to the encephalon. The progenitors of the photoreceptive cells are sited in the innermost layer of the wall of the eye vesicles, with the photosensitive portion facing inwards.

Adolescent Guatara in Stephens Island. The newborns weigh only 4-6 grams after almost one year of incubation un the sand © Paddy Ryan

In the case of the lateral eyes the outer wall of the eye vesicles invaginates to form a structure calyx shaped, with two layers (eye calyx), with the outer layer, facing the convexity, that produces the pigmented retina and the inner one, facing the concavity, produces the photosensitive nervous retina. The photoreceptors are then facing the deepest layer of the eye calyx and not the direction where the light comes from (retina of inverted type). The peduncle connecting the eye calyx to the brain will correspond to the eye nerve. The overlying epidermis will produce the cornea and the crystalline. Conversely, in the case of the parietal eye the vesicle does not invaginate to form a cup and its outer wall, or dorsal, becomes transparent transforming in crystalline whilst the inner one, adjacent to the brain, generates the pigmented retina as well as the photosensitive nervous one, that consequently presents the cellular layers inverted compared to those of the lateral eyes (non inverted retina).

Despite the strict morphological similarity with the two lateral eyes, the third eye displays interesting differences at function level. In fact, whilst in the lateral eyes the photoreceptors, that is the cones and the rod cells, generate continuously nerve impulses and are instead inhibited by the light, in the case of the parietal eye the photoreceptors excite only at the light and are instead resting when in the dark.

Usually the females lay 6-10 eggs. They take 1-3 years to produce the yolk and about 7 months for the albumen and the soft pergameneous shell © Paddy Ryan

Actually, recent studies suggest a more complex situation, with the presence of at least two types of visual pigments sensitive to different wave lengths one of which has a stimulating effect and the other inhibitory. In this way the parietal eye should have the capacity not only of furnishing information on the light intensity, but also on the colour of the light. Moreover, it seems that this organ, clearly more complex than what was thought, is also capable to perceive the polarization of light, and then able to give information of the position of the sun even with a cloudy sky.

The function of the third eye, even if not completely known, is however connected with that of the adjacent pineal gland, or epiphysis. This gland produces essentially the melatonin hormone that regulates the circadian and seasonal rhythms, therefore the alternating sleep-waking, and other functions connected with the lighting duration, such as the production of sexual hormones, the reproductive cycles and other behavioural aspects. In this sense, hence, the third eye, perceiving the light signals and so the duration of the day and of the night regulates the function of the epiphysis. It is also likely that the parietal eye intervenes in the synthesis of the vitamin D, that, as known, requires the intervention of the UV rays. In addition to the production of the melatonin, the pineal gland acts modulating some of the activities of the hypophysis.

Here hunting in the under-wood. It preys all it finds: Coleoptera, grasshoppers, worms, millipedes, spiders, but also eggs and nestlings of sea-birds © Paddy Ryan

It should be remembered that in the man, like in the other mammals, the third eye is absent but the epiphysis is however regulated by the light thanks to some neuronal circuits that connect it to the eyes. After Descartes the pineal gland should be the seat of the soul: it is not known is this can be true also in the Tuatara.

The sphenodont lives usually in own dens even if often it uses the nests of sea birds with whom it can live together. It is a mainly nocturnal animal but often it stays outdoors in broad daylight for warming up in the sun. The youngest specimens on the contrary, in general are diurnal, maybe to escape predation of the adults, as they have cannibalistic tendencies. The feeding consists mainly in invertebrates such as coleopters, grasshoppers (common preys are the wētā, a group of big grasshoppers endemic to New Zealand), worms, centipedes or spiders, but also of vertebrates like nestlings of sea birds, of which preys also the eggs, lizards and frogs. The guano of the birds with whom the Tuatara shares the habitat, and some times the nest, attracts various invertebrates with its considerable advantage. The males as well as the females defend their territory and may attack the intruders. The robust set of teeth and the powerful bite render it a good predator and a formidable opponent. The adults have usually slow movements, but in case of necessity they can perform short rides at more than 20 kilometres per hour. The young are much more lively.

This has seized a cricket. Tuatara is a slow animal, but when needed, but then rest long time to recover the strengths, is able of fast starts and run at 20 km/h © Paddy Ryan

Metabolism

The Tuatara has an optimum of body temperature between the 16 and the 21 °C, lower than most of the reptilians, usually in winter hibernates but can remain active also at low temperatures, up to about 6 °C. To this corresponds a very slow metabolism. The blood of the Tuatara presents some peculiar characteristics that are linked to its behaviour that displays a general slowness of movements alternated only by short quick shots. The haemogoblin of the sphenodont is in fact quite poorly efficient in the transportation of the oxygen from the lungs to the tissues: this, together with the low number of red blood cells present in the blood, renders the animal highly dependent from anaerobic metabolism, based on the lactic fermentation and not from a fast utilization of the oxygen. This type of oxygen rightly allows very short periods of intense activity, indispensable for catching the preys, followed by long times of recovery necessary for reintegrating the energy reserves. It is probable that this situation should be detrimental in a habitat where should be present predators and competitors more valid energetically.

Reproduction

Slow growing animals, the Tuatara reach the sexual maturity between the 10 and the 20 years, and continue to grow up to about 35 years of age.

Thanks to the big nails and its solid legs, it can also climb and move between the branches of the trees looking for preys © Paddy Ryan

During the reproductive season the skin becomes darker: it is possible that the pigmentation is influenced by the production of melatonin by the epiphysis, in turn regulated by the parietal eye sensitive to the rhythms of circadian lighting. During the courting the male walks slowly around the female with the legs rigid and the dorsal crest gets erect. For the mating, that takes place in late summer, the male mounts on the back of the female and the cloacal openings are brought into contact thanks to a twist of the rear part of the body of both partners.

During the next spring they dig in the soil a nest where they lay usually 6-10 eggs, that they remain to incubate for about one year. The kids, weighing at the birth 4-6 grams, get out by breaking the shell helping themselves with an “egg tooth” located at the apex of the snout and begin immediately to feed autonomously. Not rare are phenomena of cannibalism by adults of both sexes. The eggs have a soft, parchment-like shell. The female takes between one and three years to produce the yolk and about seven months to produce the albumen and then the shell.

Between the mating and the hatching of the eggs 12 to 15 months will pass. The reproduction occurs at intervals of 2-5 years and is the slowest among all reptilians. Equally slow are the body growth and the maturation. In fact, the Tuatara continue to grow in size up to about 35 years, the average lifespan if of about 60 years but, as we have seen, some specimens may exceed the century.

This has caught a young petrel and minces it between its interlocking teeth. The seniors, having them consumed, content of tender animals like worms, larvae and snails © Paddy Ryan

The sex of the unborn, besides from genetic causes, is determined by the temperature of incubation of the eggs, as happens also in other reptilians and in some fishes. The eggs incubated at higher temperatures produce more males, whilst at lower temperatures prevail the females. At 21 °C there is the same possibility of male or female births, whilst at 22 °C the males are the 80% and at 18 °C may be obtained all females.

Seen that the male has no penis, the mating occurs simply by apposition of the cloacas of the two partners and subsequent transfer of the sperm. The absence of the penis in the Tuatara has raised the interest of the scholars, seen that all other reptilians are equipped with this organ. Since the sphenodonts present characters considered as typical of the most primitive reptilians they have wondered if the absence of penis had to be considered as a characteristic of the first reptilians. In such case, they would have to admit that the appearance of the penis had evolved independently in the different groups.

The doubt has been resolved in 2015 from the study of the embryos of Tuatara that has proved that during the first stages of the development the penis is present but that later on it disappears, similarly to what happens for most of the birds. Since the sphenodont is rigidly protected and it is forbidden to sacrify embryos, these morphological studies have been done on old microscopic preparations set up during the first years of the XX century.

The adults, 70-80 cm long and weighing 1200 g, have a strong bite. Seen with fear and superstitious beliefs by the Maori were eaten as ritual proof of courage © G. Mazza

As a curiosity, we remember that in 1878 the physician and naturalist A. K. Newman wrote that “the Tuatara, unlike other lizards, has no penis and consequently probably has poor sexual passion” (but, on the other hand, the same author a few years later, published a study where he asserted that the Maori were a sick race, depraved and brutal, whose extinction would have not been mourned).

The Maori and the Tuatara

The relationship between the culture of the natives of New Zealand and the Tuatara is complex and heterogeneous. Usually, the Maori as in general the Polynesians, hated or feared the lizards, and by extension, the sphenodont, to which they attributed bad luck, death and various calamities: these animals represented the god Whiro, who personifies darkness and death, and even in recent times some Maori looked horrified when seeing a Tuatara. On the other hand, however, not all the groups of Maori, associate the Tuatara to this generic hostility for the lizards, to the point that it seems that the membres of some tribes ate it.

Most probably, however, seen also the fear that the Tuatara made, to eat a Tuatara was to be considered as a ritual test of courage and of initiation to get the access to priestly functions. As a proof of the fear for the sphenodonts we remind that in the mythology of the Maori, as documented by some sculptures, Kurangaituku the terrifying monster bird-woman of the forests, was accompanying the Tatuara, and this increased the fear it was aroused.

The Tuatara may live more than 100 years. The species is protected fighting the predators carried by man and reintroducing them in safe habitats © Giuseppe Mazza

However, in contrast to its negative fame, for some tribes the Tuatara was the guardian of the knowledge and often some specimens were released close to the tombs of the warriors to guard them. The Tuatara had also a place in the stories of the creation: the god Peketua in fact had done an egg with clay and, after suggestion of his brother Tane, god of the forest, had given it life, thus creating the Tuatara. After an old tale, Taurikura, spoiled daughter of a leader, behaves arrogantly with his old grandfather. Criticized by the community, repentant and shameful leaves the village and after various adventures transforms in a big lizard, in order not to be recognized by anyone. In this way the Tuatara were born.

Sicknesses of the Tatuara

In the Tatuara have been evidenced various pathologies but it is not sure which of these are really important in nature or rather only in the specimens kept in captivity. Among these we must recall some mycotic dermatitis, parasitosis caused by mites or ticks (Aponomma sphenodonti), nematodes (Hatterianema hollandiae) or Trematodes (Dolichosaccus leiolopismae).

Synonyms

Hatteria punctata Gray, 1842.