Family : Serpulidae

Text © Andrea Tarallo

English translation by Mario Beltramini

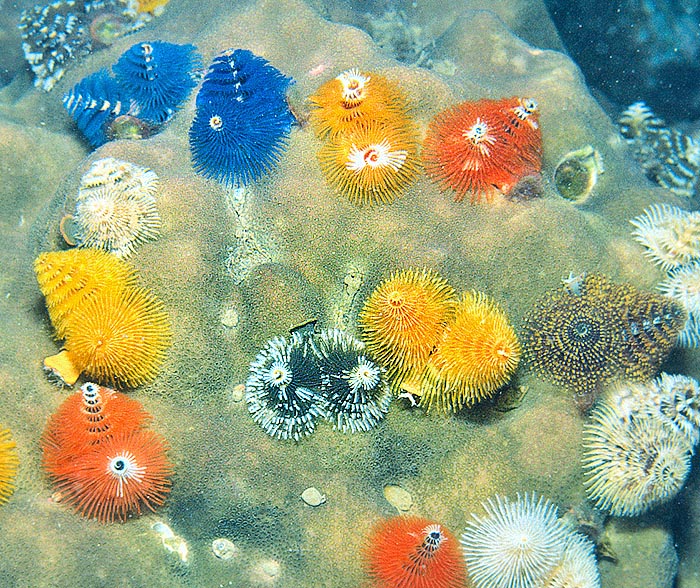

Also commonly known, rightly, as Christmas tree worm, Spirobranchus giganteus gets at once the divers eyes due to the showy bipinnate tentacles of various colours coming out from the madrepores. They can reach 2 cm © Giuseppe Mazza

The splendid polychaete worm Spirobranchus giganteus, (Pallas, 1776), commonly known as “Christmas tree” worm, rightly belongs to Phylum Annelida, to class Polichaeta, to subclass Sedentaria, to the infraclass Canalipalpata, in the sabellids’ order, family Serpulidae.

Actually, the phylogenesis of the group is not clear, or better, it is in continuous evolution, and the scientific debate is very lively about the subject.

Indeed, if on the one hand it is still doubtful if the polychaetes represent a monophyletic or polyphyletic group, that is if they come or not from a unique common ancestor, a part would like to raise them to the rank of Phylum.

The genus Spirobranchus translates essentially as “spiral gills”. This is really the most evident characteristic of its morphology, and furthermore is the only visible part of the body of the animal in its natural habitat.

The specific term giganteus, giant, might probably refer to the fact that it is one of the biggest polychaetes among the serpulids.

Zoogeography

Spirobranchus giganteus is diffused along all tropical and subtropical Atlantic coast of the American continent, from the Gulf of Mexico up to the coasts of Uruguay. It has been reported also on the African coasts of Mozambique and in the Red Sea, from where, probably across the Suez Canal, has invaded also the Mediterranean Sea.

Ecology-Habitat

The serpulid Spirobranchus giganteus lives in obliged association of alive corals, inside which it builds the tube, where it live for almost all its vital cycle. The relationship between the coral and its guest Spirobranchus giganteus may be considered as mutualistic even if it is sure that the holes produced by the polychaete weaken the structure of the coral, especially upon the death of the worm that leaves the hole empty, facilitating therefore the successive settlement of other guests even more dangerous for the coral. On the other hand, however, the current produced by the gills tuft of Spirobranchus giganteus results also in an increase of the current along the polyps of the coral, and consequently in an increase of the intake of organic material.

As it grows, it makes its way inside the coral penetrating it up to 20 cm, this protects its soft body, but in exchange, moving continuously the water with its pinnules and cilia, feeds the polyps of the madrepora and the hooks, used for going up and down in the tube, send away the starfish Acanthaster planci that destroys reefs. A symbiosis that may last tens of years © Giuseppe Mazza

Moreover, it has been recently observed that Spirobranchus giganteus, when covered by the starfish Acanthaster planci, greedy predator of corals, extroflecting the tuft and the hooks of the operculum is able to irritate the predator to the point to induce it to go away, thus acting also as protection of the coral itself.

Although if it is still not clear the relation between the two organisms, it is sure that the distribution of Spirobranchus giganteus is not casual in respect to the species it colonizes, and on the contrary exists a preference of settling on certain species, choice dictated also by the status of health of the coral where to settle.

Morpho-physiology

Spirobranchus giganteus, like all polychaetes, has a vermiform body divided in a series of segments that, apart the head and the rear portion, have each one the same structures, and each segment is identical to the other. To this characteristic is due one of the vulgar names, “segmented worms”. This species holds seven thoracic segments. As the animal leads its life permanently in a calcareous tube, the structures for the movement are reduced to hooks used for clinging to the inner walls of the tube. The prostomium, the fore segment, is the only visible part of the animal, and consists in two very showy and lively coloured, from white to orange to blue, tufts. Thanks to these tufts, that act as respiratory organ as well as filtre for catching the particles of organic material in suspension, they are easy to recognize.

The fine structure of the tufts is very paricular: it consists in bipinnate tentacles bearing very many cilia. Together, pinnules and cilia create a current allowing the optimization of the sieving work of the whole structure. The tuft is a fixed structure and the animal produces a mucilagineous substance for lubricating the tube and allowing it to quickly hide if disturbed. Typically, the animal reemerges after about one minute and very slowly for seeing if the danger has gone.

Ethology

Spirobranchus giganteus, being a tubicolous polychaete, seizes the particles of food suspended in the column of water with its modified prostomium. The latero-frontal cilia skim the frontal surface of the pinnules thus generating an alimentation current that enters from under the tentacle crown and gets out over the crown of the tentacle. Thanks to spiral or U movements of the tentacles, the two currents are neatly separated.

The reproduction is complex. When time has come to fix on the host, the planktonic larvae catch the smell of substances excreted by the conspecifics, guarantee of good hydrodynamism of the site © Giuseppe Mazza

However, the tentacles of the Spirobranchus giganteus are arranged in way of not leaving any conspicuous empty spaces. If the water travels like on the other species of serpulids, the same water is filtered more times, thus resulting in an inefficient mechanism. Most likely, some other factor in the behaviour or in the ambiental currents in nature must hinder the multiple filtering of the same water. Tests in laboratory and in their natural habitat have led to the formulation of the hypothesis that this species much more relies on the ambiental currents for feeding.

Reproductive biology

Spirobranchus giganteus has an indirect lifecycle, like all the lophotrochozoans, a group that includes many Phylums of animals, molluscs included. This means that the first phase of the lifecycle is the larval one.

In the specific case, a planktonic larva gets through a series of transformations until it finds a place where to fix. The place is chosen based on the hydrodynamism of the area, but the presence of conspecifics appears to be determinant. The larva, attracted by the substances excreted by the adults, finds its place integrating all the signals it is able to perceive from the surface of the place to colonize. At this stage the larva may undergo its final and more dramatic metamorphosis, becoming a benthic and sessile animal. It begins to build a mucopolysaccharidic tube that will be replaced by a calcareous one with the time. While growing, the adult makes its way inside the coral, inside of which it may penetrate even up to 20 cm and live even several tens of years.

The adults release simultaneously eggs and sperms in the water column, where takes place the casual meeting between the gametes. The fertilization of the egg produces the first larval phase more or less within 24 hours.

Synonyms

Cymospira bicornis Abildgaard, 1789; Cymospira cervina Quatrefages, 1866; Cymospira gigantea Pallas, 1766; Cymospira megasoma Quatrefages, 1866; Cymospira rubus Quatrefages, 1866; Olga elegantissima Jones, 1962; Penicillum marinum Seba, 1758; Pomatoceros oerstedi Voss & Voss, 1955; Serpula (Cymospira) gigantea Pallas, 1766; Serpula (Galeolaria) gigantea (Pallas, 1776); Serpula bicornis (Abildgaard, 1789); Serpula gigantea Pallas, 1766; Spirobranchus (Cymospira) giganteus (Pallas, 1776); Spirobranchus giganteus giganteus (Pallas, 1766); Spirobranchus giganteus microceras Mörch, 1863; Spirobranchus giganteus tricornis Mörch, 1863; Spirobranchus megasoma (Quatrefages, 1866); Spirobranchus tricornis Mörch, 1863; Terebella bicornis Abildgaard, 1789.