History of the Chanousia alpine botanic garden, located between France and Italy on the Small San Bernardo, over 2.000 meters high.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

He who is spending his holidays in Val d’Aosta, and wishes to find mountain flowers by the end of August, when most of the plants bear the seeds, has two options: either to take up mountain-climbing in altitude, or to take the car, and leave, following the road for the Piccolo San Bernardo.

The road starts at Pré St. Didier, and mounts, quickly, between the pine-forests, till La Thuile. Then, the trees rarefy, and when a road sign advises that you have just passed the altitude of 1.700 metres, you find yourself among the most beautiful pastures of our Alps.

First of all, you meet a small restaurant, in front of a meadow full of Great yellow gentians (Gentiana lutea), and Common butterwort (Pinguicula vulgaris), and then, on the right, the splendid lake of Verney, surrounded by snow-fields and soft small herbal cushions, typical of the “small snowy valleys”. You will walk between plants of Alpine shamrock (Trifolium alpinum), Androsaceae (Androsace carnea), Sandworts (Arenaria ciliata and Minuartia verna), Whitlow-grass (Draba aizoides), Spring gentians (Gentiana verna), and thousands of Campanulas (Campanula cochlarifolis and Campanula scheuchzeri), and Mountain violets (Viola calcarata), while coloured butterflies get around you.

Odd altitude grasshoppers, without wings, or with enlarged front legs, will look at you, curious, from the mimetic ramifications of the Cup lichens (Cladonia rangiferina). Continuing along the road of the Piccolo San Bernardo, at 2.188 metres of altitude, you find the Italian customs house (the French one is much further ahead, down in the valley), and, close to this, a charming chalet surrounded by flowers and nice drives.

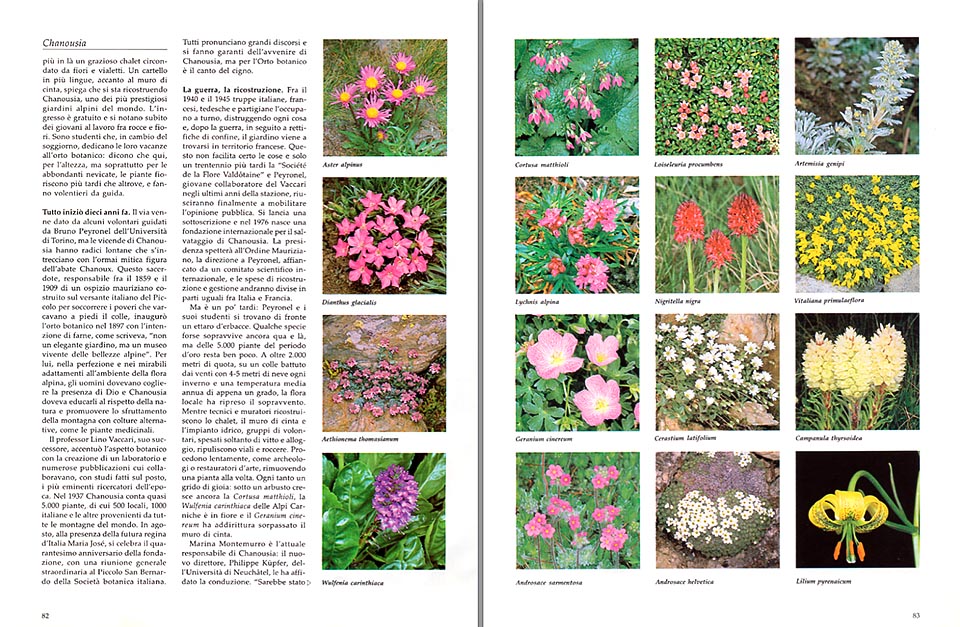

A signboard, in several languages, close to the boundary wall, explains that they are rebuilding Chanousia, one of the most prestigious Alpine gardens in the world. The entry is free and you will see at once some young people working between the rocks and flowers. They are students, who, in exchange for the stay, dedicate their holidays to the botanical orchard. They will also tell you that, due to the altitude, but mainly, due to the copious snowfalls, the plants blossom later than elsewhere and will take you, willingly, around.

All began ten years ago, with some voluntaries, led by Prof. Bruno Peyronel, of the University of Turin, but the vicissitudes of Chanousia have far away, in the time, roots, which intertwine with the, by this time, mythical personage of the abbot Chanoux.

This priest, in charge between 1859 and 1909 of a St. Maurice Order home, built on the Italian slope of the Piccolo San Bernardo, for assisting the needy who were crossing, on foot, the pass, opened, in 1897, the botanical orchard, with the intention of creating, as he wrote “not an elegant garden, but a living museum of the Alpine beauties”. After him, in the perfection and the admirable adaptations of the Alpine flora to the habitat, the men had to catch the presence of God, and Chanousia, had to educate them to the respect of nature, and to foster the exploitation of the mountain with alternative cultivations, like the medicinal plants.

Prof. Lino Vaccari, emphasized the botanical aspect with the creation of a laboratory and several publications, to which were collaborating, with studies done on the spot, the most famous researchers of that time. In 1937, Chanousia counted almost 5.000 plants, 500 of which local, 1.000 Italian, and the others coming from all the mountains of the world. In August, at the presence of Marie-José, future queen of Italy, they celebrated the fortieth anniversary from the foundation, with a general, special, assembly, held at the Piccolo San Bernardo, of the Italian Botanical Society.

All pronounced wonderful speeches, and they guaranteed the future of Chanousia, but for the botanical orchard that was the swan-song.

Between 1940 and 1945, Italian, French, German, and partisan troops occupied it in different times, destroying everything, and after the war, following to amendments made on the frontier line, the garden was located in French territory.

This, by sure, did not make the things easy, and only thirty years later, the Societé de la Flore Valdôtaine, et Peyronel, young collaborator of Vaccari during the last years of the station, were able to mobilize, at last, the public opinion. They opened a subscription, and, in 1976, came to life an international foundation for the salvage of Chanousia. The chairmanship was given to the St. Maurice Order, the direction to Peyronel, supported by an international scientific committee, and the costs of reconstruction and management were equally shared between Italy and France.

But it was rather late: Peyronel and his students met an hectare of weeds. Some species, perhaps, still survived, here and there, but very little remained of the 5.000 plants of the good old times. At more than 2.000 metres of altitude, on a mountain beaten by the winds, with 4-5 metres of snow every winter, and an average year temperature of only 1 °C, the local flora had gotten the upper hand over them.

While technicians and masons rebuilt the chalet, the boundary wall and the water plant, groups of volunteers, with all board and lodging paid, cleaned up the drives and the rocky areas. They proceeded slowly, like archaeologists or art restorers, removing a plant at a time. Every now and then, a cry of joy, and all ran to see the survivor: under a shrub still grew the Cortusa matthioli, the Wulfenia carinthiaca of the Carnic Alps was in blossom, and the Geranium cinereum had even passed over the biundary wall.

Marina Montemurro, presently in charge of Chanousia, after that Prof. Peyronel had died and the new director, Prof. Philippe Küpfler, of the University of Neûchatel, had given her the position, was between them.

It would have been much easier,, she says, starting from zero, to build the garden in another location, but Peyronel, who, before, had been working with Vaccari, strongly opposed to this project, for historical, sentimental and geographical reasons.

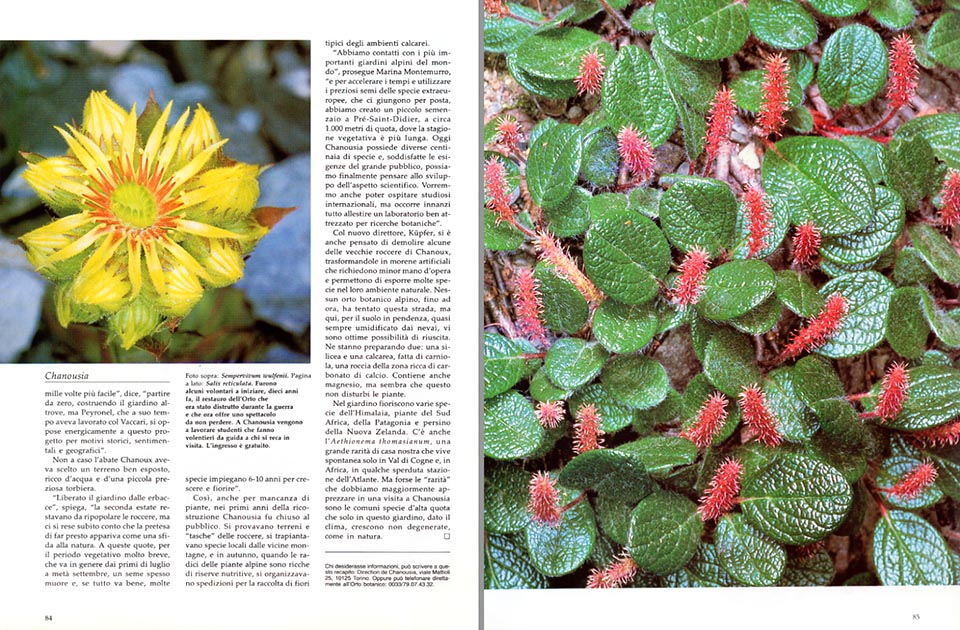

It was not by chance that the abbot Chanoux had chosen a well exposed ground, rich of water and endowed of a small, precious peat-bog. Rid the garden of the weeds, she explains to me, during the second summer it remained to repopulate the rocky areas, but they realized quickly soon that the pretension to hurry up looked like a challenge to the nature. At these altitudes, due to the very short vegetative period, which normally goes from the beginning of July to mid September, a seed often dies and, all going well, many species take 6-10 years for growing up and blooming.

So, also due to the lack of plants, Chanousia was closed to the public during the first years of the reconstruction. They had to test the grounds and the “pouches” of the rocky areas, to transport local species from the nearby mountains, and in autumn, when the roots of the Alpine plants were rich of nourishing reserves, they organized expeditions for the harvesting of flowers typical of calcareous areas.

But the other botanical orchards, did they help you?, I ask.

Sure, Marina continues, we are in touch with the most important alpine gardens of the world, and in order to speed up the times, and utilize the precious seeds of the extra European species which we receive by post, we have created a small seed-bed at Pré St. Didier, at about 1.000 metres of altitude, where the vegetative season is longer.

Nowadays, Chanousia holds several hundreds of species and, once satisfied the requirements of the public, we can at last think to the development of the scientific side. We would also like to be able to give hospitality, as it happened in the past, to international students, but it is necessary, first of all, to organize a well equipped laboratory for botanical researches.

With the new director, Küpfer, we have also thought to pull down some of the old rocky areas of Chanoux, transforming them in artificial moraines, which need less labour and allow to exhibit many species in their natural habitat. None of the existing botanical orchards, till now, has tried this way, but here, owing to the sloping ground, almost always humidified by the snow fields, there are very good chances of success.

They are preparing two of them: one siliceous and one calcareous, done of carniola, a local rock, rich of calcium carbonate. It contains also magnesium, but it seems that this does not bother the plants.

But, which are the most uncommon species of the garden? I still ask, before leaving, like all passing-by journalists.

Marina smiles, because she had been waiting for the question, and tries to change the subject: It is an information which is never given to the press, as we fear of thefts, she admits.

I see that in the garden are blooming various species of Himalayas, plants of South America, of Patagonia, and even of New Zealand. There is also the Aethionema thomasianum, a true rarity of our country, which lives spontaneously only in the Valley of Cogne, and, in Africa, in some solitary stations of the Atlas Mountains. Paradoxically, however, after me, the “rarities” which we must mainly appreciate during a visit to Chanousia, are the common great altitude species, which, only in this garden, thanks to the climate, grow up without degeneration, like in the wild, in all their full beauty.

GARDENIA – 1987