Famiglia : Fagaceae

Text © Prof. Giorgio Venturini

English translation by Mario Beltramini

The European chestnut (Castanea sativa) belongs to the same family of the beeches and oaks © G. Mazza

The Chestnut ( Castanea sativa Mill., 1768 ), is a tree of the family of the Fagaceae, family to which belong also, as more representative membres in Europe, also the beech and the oaks. To the genus Castanea, besides the chestnut, belong other eight species, three of which of remarkable present or past food economical importance, namely the American chestnut ( Castanea dentata ), the Chinese chestnut ( Castanea mollissima ) and the Japanese chestnut ( Castanea crenata ).

The chestnuts are not to be mistaken with the Horse-chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum), a Sapindaceae tree diffused in Italy as ornamental, that produces a fruit externally quite similar to the chestnut but of very bad taste and slightly toxic.

Castanea is the Latine name of the chestnut, in its turn derived from the Greek “castanon” (κάστανον). After Nicander of Colophon (Greek poet and physician of the II century BC), the name of the tree should come from the city of Kastanèia, in Thessaly, at that time rich of chestnuts, but it is also possible that, conversely, the name of the city should come from that of the trees (we can think to how many countries in Italy are called Castagnola, Castagneto, etc.). The specific name sativus in Latin means cultivated.

A fanciful etymology is the one proposed by Saint Isidore of Seville (VI-VII century) who affirmed that the chestnuts have the shape of the testicles and that their name comes from the verb “castrare”: because, the operation done opening the prickly cupule to extract the fruits is similar to that done for taking off the testicles during the castration.

Maybe Isidore, as a Doctor of the Church, was forgetting that the testicles are two and the chestnuts are usually three, however it is true that they say “to castrate the chestnuts” to describe the operation done by the roaster of chestnuts when he incides the chestnuts before cooking them in order to avoid their explosion.

About the origin of the chestnut two hypotheses have been advanced. After the first one, the tree should be native to Asia Minor and the eastern regions of the Mediterranean basin and then should have been spread by man since the antiquity in most of the temperate regions of Europe. After the second one, supported by paleo palynological data (that is, from the study of the old pollens), the chestnut should have occupied in the past a vast area extended to much of Europe and of Middle East.

During the last ice age the chestnut should have disappeared in most of these territories, surviving in few other refugium areas. Starting from these refugia the human intervention should have led to its new diffusion.

The Chestnut is a deciduous tree that may reach a height of more than 30 metres. The trunk can have the diametre of some metres (specimens are known having a trunk of more than 6 m) and is usually straight with big and long branches that grant the top a roundish posture.

The trunk, with the bark deeply marks by vertical and spiral grooves, can be 30 m tall © Giuseppe Mazza

The plant is very long-lived as may exceed the 500 years of life and specimens are known attributed an age of about 1000 years.

In the young tree the bark is smooth and of olive colour marked by oval lenticels, in the adult is grey-brown and is deeply marked by vertical and often spiral grooves.

From the base are often emitted numerous fast growing suckers, characterized by a smooth and reddish bark with numerous elliptical lenticels (the lenticels are structures of the bark that correspond to a discontinuity of the suberic waterproof layer and consequently allow the gas exchanges.

The leaves, alternatively arranged, are simple, with toothed margin and of elliptic-lanceolate shape, with evident nervations; the young ones are morbid and tomentose, the adult ones are coriaceous and glossy, up to more than 20 cm long and up to 10 cm broad. The upper page of the leaves is of intense green colour, whilst the lower one is paler. The appearance of the leaves is late, for this reason in spring the chestnut appears barren in respect to other trees of the wood of broad-leaved trees.

Also the blooming is late, the flowers are unisexual and the same plant bears male and female flowers.

The male flowers, grouped in glomerules, form erect aments, up to 30 cm long, that generate at the axil of the leaves. The male flower, white-yellowish, has a perianth subdivided in six lobes and 6-15 thin stamens. The female flowers are merged in groups of 2-3, covered by a cupule of bracts that will form the husk.

The inflorescences can bear only male flowers as well as both male and female flowers, where these last are located at the base of the ament. More rarely, we can find only female inflorescences.

The species is proterandrous, that is, with the male flowers ripening before the female ones. This condition avoids the self-pollination, that is further prevented by phenomena of self-incompatibility. Moreover, in some varieties some specimens have sterile male flowers and for the reproduction they therefore depend on the presence in the same wood of other fertile individuals. The male flowers, due to their smell, quite penetrating, and the production of nectar are quite attractive for the insects, such as bees, dipterans and coleopterans. Despite this, the pollination is basically anemophilous, as the female flowers do not attract the insect who visit them and will be able to pollinate them only casually.

The fruit, called chestnut, is a globose, more or less pointed, achene with a convex side and one flat, covered by a pericarp (peel or skin), coriaceous and of more or less dark brown colour depending on the variety, glossy outside and tomentose inside and, more internally, by a thin membrane, called episperm.

Very long-lived species, that may pass the 5 centuries, the Castanea sativa often develops at the base several fast growing suckers, characterized by smooth and reddish bark with numerous elliptical lenticels © Giuseppe Mazza

The fruits, usually two and three, but at times up to seven, are contained in the spiny involucre, the cupule, bristling with thin and acuminate thorns (quite sharp), that comes from the cupule that was covering the female flowers. The acuminate pole of the fruit has a small fringed protrusion, called torch or wick that represents a residual of the stigma, whilst the opposite pole, flattened, shows the hilar scar corresponding to the touch point between cupule and chestnut.

When ripe, the husk opens in four valves, letting out the fruits. The cultivated varieties mainly differ due to the characters of the chestnut, as size, taste, colour, etc.

The most known variety is the marron, usually of big dimensions, with relatively clear and streaked and with the epispermnthat, contrary to what happens in other varieties and in the wild chestnuts, does not penetrate inside the pulp, thus rendering easier the peeling.

Whilst in the wild varieties every cupula may bear three or more chestnuts, in the cultivated varieties such as the marron the cupula contains only two or sometimes one chestnut.

The wood of the chestnut is compact and elastic and is utilized for the construction of beams for houses, of furniture or of casks. Both the bark and the wood are rich of tannins that make it resistant to rottenness, and for this reason the chestnut is utilized for the extraction of the tannins used for the tanning of the leather and as mordant for dyes.

Habitat and distribution

The chestnut is a mesophilic tree, which means that it develops well in environmental conditions not extreme such as humidity and temperature. In the Alpine zones it is found between the 200 and the 800 m above the sea level, whilst in southern Apennines it can reach the 1000-1300 or even the 1500 m of altitude in Sicily. It is an acidophilic species, so it keeps away from calcareous soils unless particular conditions where, for instance, the excess of calcium has been removed by local situations.

Castanea sativa is spread in all Southern Europe, north-western Africa, Turkey and Balkans up to Caucasus. Thanks to man work, settlements north of Alps do exist up to even Great Britain, where, however, it fructifies with difficulty. In Italy it grows in all the Apennines, in Sardinia and Sicily, in the Prealps and in the western part of the Alps and is the indicator species of the phytoclimatic zone called Castanetum.

The here enlarged lenticels are particular structures of the bark corresponding to a discontinuity of the suberic waterproof layer to allow, as occurs for the stomata of the leaves, gassy exchanges © Giuseppe Mazza

Besides the production of wood and of chestnuts, the tree has a remarkable ecological, economical and alimentary importance thanks to the mycorrhizae, that is the symbiotic associations that occur among its roots and the hyphae of numerous fungi, some of them of significant nutritional and commercial importance such as, for instance, the penny buns.

As result of this phenomenon the chestnut woods are important producers of these mushrooms and of other edible ones.

The chestnut in the alimentation

In the modern cuisine the chestnuts occupies a marginal place, practically as titbits, in a quite limited number of recipes.

Everybody knows the castagnaccio (a sort of chestnut cake), the marrons glacés and the Mont Blanc and in autumn in all cities they sell the roasted chestnuts but other utilizations are absolutely occasional.

To confirm this it is sufficient to read Artusi’s cookbook, “The Science of Cooking and the Art of Fine dining” that rightly cites the castagnaccio and few refined desserts but comments that the chestnut “… in the people, and for those who do not fear the winds, is a cheap food, healthy and nourishing” and consequently relegates its use to the lowest layers of the society.

On the other hand, about two centuries before Francesco Moneti, author active between the second half of the XVII and the beginning of the XVIII century wrote “the castagnaccio is a delicate food for those who are a little less than a human being and a little more than the bestial being” and other authors of the same age underline that this food stands at the base of the bestiality and of the rural lasciviousness. Yet in the Greek and Roman antiquity, the chestnuts were very much appreciated, exalted by Virgil, cited in the recipes of the famous gastronome Apicius, contemporary of Augustus, and appreciated by the last emperor Romulus Augustulus.

It is interesting to try to explain the causes of this image decline of the chestnut. Due to man’s work, the extension of the chestnut woods in Europe, and particularly in Italy, had had a big increase at the times of the Roman Empire, growth that had continued in the following centuries, with the decline of the Empire and the barbarian invasions, together with the diminution of the areas destined for agriculture. In this period the chestnut has an important role as dietary supplement; associated to the wheat and other foodstuffs, and is widely consumed in all social strata, also as voluptuary food.

Castanea sativa is a species needing acidic soils and habitat conditions not extreme with humidity and temperature. In the Alpine zones grows between 200 and 800 m of altitude, but in southern Apennines 1000-1300 m and even 1500 m in Sicily. Is diffused in all southern Europe, north-western Africa, Turkey and Balkans up to Caucasus, but cultivated is found also in Great Britain, like this spectacular huge specimen with an unusual enlarged base, of Kew Gardens in London © Giuseppe Mazza

The big consumption of course stimulates the proliferation of new recipes and the chestnut is used, fresh, dried or as flour for preparing soups, side dishes and desserts, as proved by the recipe books that describe extremely elaborate delicacies based on chestnuts. During these centuries, particularly in northern Italy, are selected increasingly numerous varieties of high quality chestnuts and the value of the produce is proved by the fact that in many regions the countrymen did pay with chestnuts the tithes and tributes due to the landlords.

Starting from the end of the XV century, part of Europe, and especially Italy are hit by the great crisis that culminates in the XVI and XVII centuries. With the Italian Wars between France, Spain and Holy Roman Empire, Italy, object of the dispute, is crossed by armies that carry devastations and diseases (we remember the Landsknechts and the Great Plague of Milan of Manzoni’s memory). To this we have to add a climatic factor, the so called Little Ace Age, that struck Europe during those centuries. These factors caused terrible famines, destruction of the cultivated fields and depopulation of the countryside, with the rural populations that took refuge in the woods and on the mountains in order to get far from the war, pestilences and misery.

The unisexual flowers grow on the same plant but to avoid self-fecundation the species is proterandrous, that is, the male flowers ripe before the female ones. The inflorescences can be only male, mixed with small female inflorescences half hidden at the base of the catkins or rarely are female © Giuseppe Mazza

The chestnut became an essential food, now replacing the bread, used for preparing the polenta and, mixed with acorn flour and a little of wheat flour to prepare the bread (the wooden bread or tree bread); it becomes, then, together with the acorns the food of those semi-bestial wretched so much despised by Francesco Moneti “…we can see that from those countries where they live only of castagnaccio get out characters of gross manners and in every way uncivilized, indiscreet and badly grown”. With such biases it is clear that the chestnuts could not be too much estimated as food suitable for honest persons.

With the easing of the crisis the food situation in the country did improve and the chestnut gradually resumed its role of supplementary food and not, any more, as replacement, however remaining of primary importance in the mountain regions where the chestnut woods had their maximum diffusion. Here, until the years just before and after of the second world war, reigned an agriculture of subsistence and the country families lived basically with the products of their lands: small quantities of wheat and corn, potatoes, a few heads of cattle, the products of the kitchen garden and of the farmyard and especially of the wood, that gave them wood, chestnuts and mushrooms. These three last products, besides for the internal use, were also the only ones that could be object of commerce with the cities.

The nectar, that attracts with its pungent smell bees, dipterans and coleopterans, is produced only by the male inflorescences but pollination is paradoxically entrusted to the wind because the female inflorescences oddly don’t have anything to offer to insects, that at most hit them in flight pollinating them by chance © Giuseppe Mazza

In many valleys, in Italy and elsewhere, the polenta of chestnuts with addition of milk or the dried chestnuts cooked in milk represented until a few decades ago one of the main foods of the day. In order to describe this situation, they were talking of a “civilization of the chestnuts”.

The chestnut, food of the dead

Fruit that typically in nature ripens in full autumn, the chestnut since the Middle Ages is in many countries associated to the day of the dead, November 2nd.

So, in France they placed some chestnuts under the pillow as an offering for the dead, to prevent dirty tricks by the spirits or, also, they left on the evening of Nov. 2nd in group into the wood to cook chestnuts.

In various Italian regions, in the popular belief that on Nov. 2nd the dead came back in the house where they had spent their life, they used to go to the cemetery for the traditional visit leaving the doors open and on the set table roasted or boiled chestnuts (of course, once back home they did eat the chestnuts eventually left behind by the dead).

After another habit on the day of the dead the hosts offered the clients some roasted chestnuts as a symbolic propitiatory rite.

We find another utilization of the chestnuts linked to the month of November in the famous American recipe of the turkey stuffed with chestnuts, prepared traditionally for the Thanksgiving Day that takes place in USA on the fourth Thursday of November.

After the tradition this holiday was celebrated for the first time in 1621 in Plymouth (Massachusetts) by the Pilgrim Fathers arrived with the vessel Mayflower. As they were not able to adapt their techniques of cultivation to the American climate, the settlers were starving and were saved by the natives who brought them food and taught them the use of the local resources. To thank God and the natives and celebrate the friendship within them and the settlers, the Pilgrim Fathers organized a holiday based on turkey stuffed of chestnuts (at that time they were American chestnuts, fruit of the Castanea dentata, nowadays practically disappeared). Then we know well how they ended up the gratitude and the friendship!

Tree laden with growing husks. They are the real fruits as the chestnuts we eat botanically are seeds © G. Mazza

Nutritive power of chestnuts

The chestnuts has a high contents of carbohydrates, particularly starch and consequently is a very caloric food, it contains also some vitamins, notably vitamin A, vitamins of the group B and vitamin C and is also a good source of mineral salts.

As main food the chestnut is effective in filling the stomach and in calming hunger, besides in furnishing the necessary calories in form of starch, due to its low protein contents however it alone cannot satisfy the daily necessities. As proof of this inadequacy, we remember that still around 1960 they have reported in the Piacenza Apennines cases of malnutrition in children weaned with chestnut-flour based paps.

Having no gluten the chestnut flour cannot leaven well and consequently is not suitable for making bread, except with the addition of wheat flour.

The chestnut has the fame of being a food that favours the meteorism and flatulence, as we have already seen.

This unpleasant effect is due to the presence of non-digestible sugars (oligosaccharides) that in our bowel get a fermentation due to the bacterial flora, thus releasing many gasses.

Cosmetic and medicinal uses

Infusions of leaves and the bark of the chestnut are utilized in herbal medicine for external use, as astringent and bland disinfectant of the skin and of the mucous membranes , as well as for internal use as sedative of cough and as antiseptic of the airways. The cooking water of the chestnut skins has a cosmetic use as after-shampooing.

Chestnut honey

The male flowers do attract the bees, who with the pollen foraged produce an excellent honey having a slightly bitterish taste, quite characteristic, that renders it much sought commercially.

The traditional chestnut harvest

The chestnuts wood was subject of cares that consisted in pruning the trees and in the removal of the suckers. The underwood was kept clean eliminating the bushes. In the vicinity of the collection, depending on the regions between late September and late October, they proceeded to rake the leaves that were carried in special farms and then used as litter for the livestock (nowadays, most of the chestnut woods are abandoned and invaded by the underwood whilst the trees, not pruned and cared any more have just a poor production of small chestnuts). The harvesting of the chestnuts was done almost every day during the period of the fall of the fruits, with the help of a stick or with other tools for opening the closed husks.

Husks open for disseminating. The spiny involucre may contain even 7 chestnuts, but usually hosts 3 and in the big sized cultivated varieties, like the marrons, even only one chestnut may be found © Giuseppe Mazza

It was and is still important the daily or almost daily collection as the chestnuts remaining on the ground, besides being prey of rodents and other animals, are exposed to fungal infections and undergo a desiccation.

The collected chestnuts were put in a wicker basket or in an apron and then carried home for the direct consumption of the fresh fruit or for the sale or otherwise in a special small farm in the wood, where they proceeded to the desiccation. The inner space of these constructions, built in stone, that depending on the regions had different names as, for instance, in Tuscany, metati, in other regions casoni, secadiu, seccarezzu, in Corsica grataghiu, in France clédié or secadou, was subdivided in two floors by wooden beams.

Over the beam the chestnuts were arranged on suitable drying racks (called in some regions cannicci, graia, graa or gre), whilst below a flameless fire was kept burning fed with chestnut prunings and the skins of the chestnuts of the previous year that went on burning for various days, while the chestnuts were periodically stirred with rakes. Once the desiccation was completed, the chestnuts were peeled off, usually placing them inside a robust canvas bag that then was slammed for a long time on a stump and finally they separated the fruits from the skins with the sieves.

The dried chestnuts could be conserved or sent to the mill for the production of the flour. Usually the mills had some grindstones specifically intended for the chestnuts. In the case the exsiccation is not complete, the chestnuts can remain relatively soft, to this product in Lazio they give the name of “mosciarelle”.

During the time of the fall of the chestnuts the collection was reserved to the owner of the wood and it was forbidden to send the pigs to graze inside it. In many regions was deliberated a date after which everybody could enter the wood to glean the chestnuts and the grazing of the pigs could be resumed. The rural communities engaged collectively in the defense of the wood and some leaders were appointed, responsible for monitoring the woods in order to prevent possible damages caused by man or by animals.

Looking closely a chestnut we discover a small fringed ledge, called torch or wick, that is a residue of the stigma, the female organ intended to intercept the pollen © Giuseppe Mazza

Modern chestnut cultivation

The production of chestnuts from a tree begins around the fifteenth year of age and reaches the top by around the 80th year. Of primary importance for the production has the introduction of rational farming techniques, with the choice of varieties of Castanea sativaof high quality planted with optimal distribution on soils appropriately chosen, rational pruning, regular fertilization and prevention or treatment of the pathologies. To this we have to add the adoption of mechanized methods of collection in lieu of or in addition to the manual collection.

As a result, against a production of about 3-4 quintals per hectare in an extensive chestnut wood with traditional cultivation, in a wood traditional but rationalized or a new plant we may reach the 45-50 quintals per hectare.

The mechanized harvest that utilizes essentially systems of aspiration similar to huge vacuum cleaners allows a strong reduction of the costs of the manpower (10-30 kg/hour in the manual collection, 800-1000 kg/hour in the mechanized one). Moreover, the mechanized collection removes from the ground the infested and damaged chestnuts, that, conversely, are ignored in the manual collection, and so causes a decrease of the power of future infestation of the ground.

Heterospecific hybrids and graftings

During these last years we see the tendency to utilize, when planting chestnut woods, hybrid specimens or grafts between the European chestnut and the eastern ones, Castanea mollissima or Castanea crenata. Compared with the European chestnut these plants can represent some advantages, like a greater resistance to pathologies, greater precocity of the production beginning of the tree, smaller trees hence more easily managed and finally bigger fruits.

On the other hand, some disadvantages do exist such as minor adaptability and resistance to adverse conditions and to the frost and mainly less appreciated taste and consistency. To this we have to add the risks linked to the introduction of alien species in terms of biodiversity and of possible introduction of pathogens (please refer to the section concerning the diseases of the chestnut). Worldwide, the annual production is of about 1,2 million of tons, the largest producer is China, followed by South Korea (but in these instances it’s matter of the fruits of the Chinese chestnut, Castanea mollissima and not of the European chestnut, Turkey and Italy.

Presently in Italy are often commercialized the fruits of the Chinese chestnut as “marroni” (big chestnuts). It is a food fraud and the buyer is cheated by the big size of the fruits, which have however lower organoleptic characteristics of than the European chestnuts. In Italy the chestnut wood is present on 788.000 hectares, equal to the 7,5% of the forest area and to the 2,6% of the territorial one. The chestnut surface is covered for about the 20/% by fruit chestnuts and for the remainder by wood chestnuts that may be governed as coppice.

The opposite pole of the chestnuts displays instead the typical hilum scar corresponding to the contact point between husk and chestnut, where passed the food © G. Mazza

In the first case, with shifts of 10-15 years, are taken off the suckers that emerge from the stumps remaining on the ground after the cutting down of a tree and from these they get poles for supporting the vines, telegraphic poles, staves of casks and charcoal. Conversely, the high woods are tall trees that derive from seed and are cut with a renewal shift of about 80-100 years. The wood in this case is used for the construction of furniture, fixtures and blinds, floors or other.

The most extensive chestnuts woods are located in Calabria, Tuscany, Piedmont and Liguria, but are in constant decrease due to the depopulation of the mountains, the diseases and the fires and most of them have gone wild and consequently are of no importance on a productive point of view. The Italian production that till the end of the XIX century was the first in the world, with values eight times higher than the current ones, has met a progressive decline and only during the last thirty years has halved.

On top marrons with relevant section and normal cut chestnuts in comparison. The marrons distinguish for the relatively pale and striked skin and with episperm that, contrary to what occurs in other varieties and in wild chestnuts, does not enter the pulp, rendering consequently the peeling much easier © Giorgio Venturini

Presently, the Italian production is of about 50.000 tons per year, of which 24.000 come from Campania, 9000 from Calabria, 7000 from Lazio, 3700 from Tuscany and 2000 from Piedmont. In economic terms Campania and Lazio are the most important regions thanks to the best quality of the product. During the last few years we have noted a reversal trend due to the growing employment of modern cultivation techniques and of high quality varieties.

Among the other European countries producers of chestnuts, we remind Spain, with most of its production in Galicia, and France, mainly in Corsica, Ardèche and Dordogne.

Chestnuts conservation

Chestnuts damaged mechanically are less preservable than the intact ones, in particular cracks in the bark or damage of the apical pole can represent entrance routes for mold parasites. The chestnuts intended for consumption fresh, then to be prepared roasted or boiled, are usually subject to the hydrotherapy, that consist in putting them in water for 8-9 days and then left to dry up.

This treatment eliminates most of the parasites and favours the development of an anaerobic bacterial flora that begins a fermentation that, producing lactic acid, favours the conservation.

A traditional method for conserving the chestnuts, now almost obsolete, is that of the “ricciaia” (place where the chestnuts were collected): the ches tnuts, still contained in the husks, are piled in a clean space in the wood and covered with chestnut leaves and stones. Under these conditions, the chestnuts preserve for some months, undergoing a slight fermentation process analogous to that seen in the hydrotherapy.

A particular form of treatment is that producing the so called “chestnuts of the priest”, typical to Campania. In this case the fruits are exsiccated like for the production of the dried chestnuts, then roasted in oven and finally rehydrated by immersing them in water and wine.

Diseases and parasites

The chestnut may be targetted by various pathogens, the most important being oomycetes, fungi and insects.

The ink disease. Phytophthora cambivora is an oomycete (the oomycetes were in the past included in the fungi kingdom, whilst nowadays they are considered as belonging to the kingdom of the Chromista), responsible of the so called ink disease, of Asian origin and imported probably via Portugal since the ’800.

This disease, present in Italy since the last century, has diffused in all chestnut zones and is causing quite serious damage to the chestnut woods, in particular to those growing in the most humid zones. The disease manifests with the blackening of the roots and the appearance of dark spots on the tissues of the stem. The affected parts produce an exudate black like ink that gives the name to the disease. The affected plant meets a rapid weakening and the death usually occurs within 3-4 years, but even much more quickly in case of very serious infections.

The chestnut blight is a serious necrotic disease caused by the fungus Ascomycota Cryphonectria (Endothia) parasitica. The parasite penetrates the plant through wounds of casual origin or caused by graftings or prunings or by other pathogens. The affected areas initially display a rusty red colour and then meet a necrosis and expand on the invaded branch to surround it completely causing its desiccation. The surrounding tissues grow causing the characteristic cankers. In the most serious instances we may reach the desiccation of the whole plant.

Gemma and lenticels closing for the winter rest. The vegetative restart of the chestnut is late and in spring the tree appears barren compared to the other trees © G. Mazza

The Cryphonectria is of Asian origin and has reached the USA by the beginning of the ’900 thanks to specimens of Japanese chestnuts ( Castanea crenata ) that, starting from 1890, were imported for the production of chestnuts, considering advantageous the size of the Asian species smaller than the American one and hence advantageous in terms of surface of occupied land. The first American case of infection was described in 1904 on a tree growing in the Bronx Zoo, New York and by mid XX century the American chestnut, having no resistance against the fungus, had practically disappeared.

It is estimated that more than three billions of chestnuts have died, with an enormous economic damage and an even bigger ecological one, considering the flora and the fauna depending from the chestnut. The damage has been further aggravated by the containment attempts of the infection that have caused the felling of healthy trees, thus eliminating individuals casually resistant that might have started a repopulation.

The chestnut can be target of various pathogens and parasites, most important of which are oomycetes, fungi and insects. Two moths of the genus Cydia, lay for instance hundreds of eggs on the leaves and the caterpillars move inside the husks. They eat the growing chestnuts for about one month and then fall on the soil pupating. The holes dug into the fruits may damage even the 50% of the harvest © G. Venturini

Castanea dentata, an imposing tree up to more than 40 metres tall, that produced huge quantities of chestnuts, that, before the infection, did occupy a very vast area from the USA Atlantic coast up to the Appalachian Mountains, to Mississippi and Ohio, is nowadays reduced practically to few specimens with a shrubby posture.

The fungus has then reached Europe (the first case reported dates 1938, in Liguria) and soon has practically diffused all over the continent, but, thanks to the bigger resistance of the European chestnut and to the appearance of less virulent strains of the fungus, the damages have not had the catastrophic consequences seen in America. The reduction of virulence is due to the infection of the fungus done by a virus.

The struggle against the cortical canker develops on various fronts.

An approach is that of the hybridization that tends to obtain trees of American or European chestnut hybridized with the Asian species resistant to the fungus. The work is slow and difficult as by each generation is necessary to select the specimens showing a greater resistance and cross them with the autochthonous chestnuts in order to maintain the resistance as well as the positive characteristics and the genome of the American (or European) chestnut. Presently, promising results have been obtained.

A second approach exploits those same viruses, called Hypovirus, responsible of the decrease of the virulence found in the European strains of the fungus and that has rendered possible the survival of the European chestnuts. By infecting with the virus fungal strains highly pathogenic, they tend to reduce their dangerousness. This method has given promising results in Europe, but less in America. The third approach takes advantage from the biotechnologies and has led to the production of trees genetically modified, called Darling4, that express a gene coming from the wheat. This gene, called OxO, present in many plants but the chestnut, produces an enzyme, the oxalate ossidase, that acts as defence against many fungi. To understand the mechanism, we must know that the fungus produces oxalic acid and this molecule kills the tissues of the infected tree. The enzyme destroys the oxalic acid and so the plant is not seriously damaged by the fungal infection.

A parasite of Asian origin, arrived in Europe quite recently is a hymenopteran insect, that is a small wasp called Asian chestnut gall wasp ( Dryocosmus kuriphilus ). This insect has reached Europe in 2002 after an importation of infected Chinese chestnuts and the first cases have been observed in Italy, in the province of Cuneo. During the following years have been infected the chestnut woods of most Italian regions.

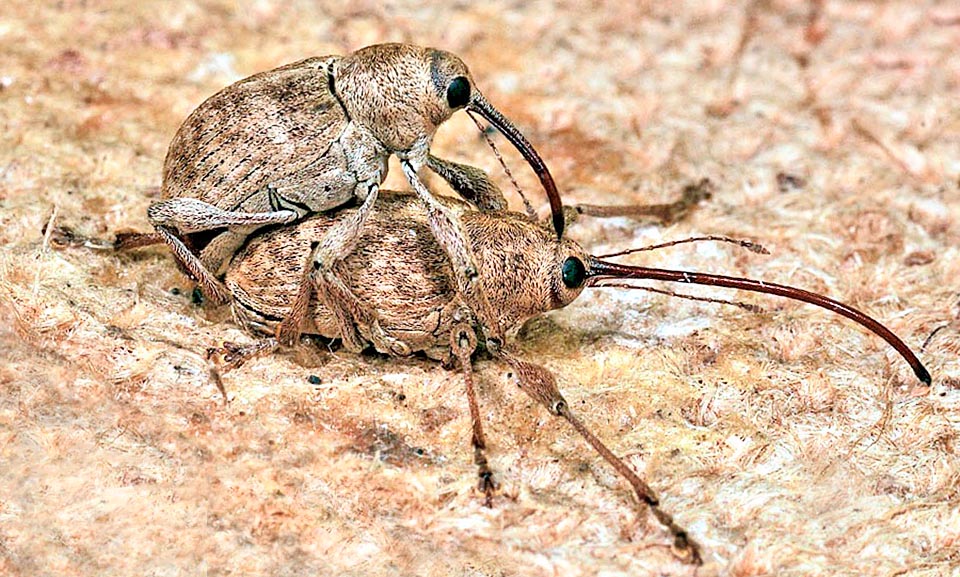

Curculio elephas, here coupling, causes similar damages, that lays directly on the chestnuts and to these harmful insects have added others imported © Giancarlo Medici

The absence in Europe of natural antagonists of the insect has facilitated its diffusion. The Asian gall wasp is reported also in other European countries, such as, for instance, France and Slovenia as well as in USA.

It is worldwide the most harmful pest for the chestnuts. The female, tiny wasp long two or three millimetres, lays during the summer about a hundred eggs inside the young gemmae of the chestnut. The eggs develop parthenogenetically and produce the larvae during the following spring, when the gemmae develop and cause the formation of galls of about 2 cm of diametre, that are woody hollow formations, inside which the larva grows up and metamorphoses producing the new adults.

The galls damage seriously the plant interfering with the growth of the buds and with the fructification, that is reduced even of the 70% with very serious commercial damages. As further serious consequence the galls facilitate the infection by the fungus responsible of the cortical canker.

Here for instance a leaf damaged by the galls produced by the Asian gall wasp (Dryocosmus kuriphilus), a parasite of Asian origin, arrived in Europe quite recently. A very sml wasp not more than 2-3 mm long © Michel Di Bari

The treatments with traditional insecticides are very ineffective, as the larvae develop inside the galls that protect them from the chemical means.

More promising is considered by many the biological fight with the parasitoid hymenopter Torymus sinensis, introduced from China. This insect lays its eggs inside the gall produced by the Asian gall wasp and the larvae getting out from the eggs eat the larvae of the Dryocosmus.

We must now describe the harmful insects that, as consumer, we observe more frequently, that is those that are commonly defined the “worms of the chestnuts”. All of us had to peel a roasted chestnut and to find it “maggoty”, that is hollowed, with blackened parts and often a small worm inside, and consequently uneatable.

Responsible of these unpleasant damages, of huge economic importance, are basically some small lepidopterans, that is some small moths of the genus Cydia (Cydia splendana and Cydia fagiglandana) called chestnut tortrix or beech moth.

The female in summer lays some hundreds of eggs on the leaves of the chestnut, within about 10 days develop from the larvae that enter the cupule through the hilum and then ion the chestnut of which they nourish for about one month. Once out from the fruit through a hole that they make in the skin, they fall on the soil where they form a cocoon and winter there finally metamorphosing and flickering in the middle of summer.

As the affected fruit is of no commercial value, the Cydia can cause very serious damages, seen that in some chestnut woods the percentage of affected chestnuts may be very high, even up to the 50%.

The struggle against the Cydia is mainly preventive and consists in the timely collection and the elimination of the affected chestnuts, in order to prevent high infestations during the successive year. Also a small curculionid coleopteran, the chestnut weevil ( Curculio elephas ) infests the chestnuts with its larvae, with a mechanism similar to that of the Cydia.

Concluding this paragraph concerning the diseases of the chestnut we wish to underline that among these the most devastating are of exotic origin and come from the import of not duly controlled parasitized trees. A similar situation has occurred also for the diseases of other plants, such as the Dutch elm disease, caused by the Ophiostoma ulmi, imported with the wood from Asia, that has caused the death of millions of elms or the red palm weevil, that is the curculionid coleopteran Rhynchophorus ferrugineus, imported from Asia with some palms, that causes terrible damages in most of Middle East and the Mediterranean countries. Particularly affected economically are the countries producers of dates. And similar superficiality occurs for the import of exotic species utilized for the biological control of parasites, that often can be bought online without any control. It is emblematic the case of the Asian ladybeetle ( Harmonia axyridis ), Asian species imported in USA and in Europe for fighting aphids and mealybugs, that has multiplied enormously causing serious damages to the ecosystem, the health of man and to the economy.

One of the last arrivals is that of the Asian stink bug Halyomorpha halys, a pentatomid arrived probably from China by container or other means, that is causing very serious damages to the fruit farming in Italy as well as in other European countries and in America.

It is here with the enlarged larvae in the right image inside the gall. In summer the Dryocosmus kuriphilus lays the eggs on the gemmae of the chestnuts and the following year, in spring, when the leaves open, the young larvae wake up and eat the tissues causing the formation of galls. Welcoming small 2 cm chambers where find food and shelter till the metamorphosis with the adult’s exit. Obviously, the plant suffers and the chestnuts production may decrease of 70% © Giovanni Bosio

It is worth to note the fact that in spite of a now secular experience of damages to our flora and fauna, the controls on the imported plants and animals are neglected and that the public opinion ignores this problem increasingly serious in a globalized world where the intercontinental transports occur daily. On the opposite end, the governments and the public opinion of many countries are sensitive in an exasperated way to the problem of the genetically modified organisms and oppose to their use despite the fact that in this case the controls are extremely tight.

Chestnut in art

The citations of the chestnut tree and of its fruits in literature are very numerous. Here are shown some examples, like these Peppino Mereu’s, ’800 Sardinian poet, verses, about the interest linked to the chestnut bread, land and acorns:

« Famidos nois semos pappande pane e castanza, terra cun lande terra ch’a fangu, torrat su poveru senz’alimentu, senza ricoveru. » (We are eating chestnut bread and land with acorns, land with mud, the poor man is again without food, without shelter.)

To reduce with no poisons this pest has been recently introduced from China the parasitoid hymenopter Torymus sinensis that lays, look at the case, its eggs in the galls of Dryocosmus kuriphilus. The larvae that are born, right on the photo, devour those of the Asian gall wasp thus reducing at least the number of parasites © Giovanni Bosio

The bread of chestnuts, acorns, land (that is, clay) and ash, (su pan’ispeli), already cited by Pliny in the first century, has really represented until a few decades ago a Sardinian (Ogliastra) country food and also of other regions. The clay was employed instead of the gluten to bind the dough, as well as providing mineral salts and completing the effect of satiety, whilst the ash helped in taking off the astringent effect and the tannin of the acorns. Also many animals, like, for instance, the parrots, eat often clay as source of mineral salts and as depurative.

Less seriously, we quote from “Bertoldo, Bertoldino e Cacasenno” (Giulio Cesare Croce and Adriano Bianchieri, 1620), where are celebrated the virtues of the castanaccio: “Così dianzi cessò da le strillate Cacasenno, in virtù d’un castagnaccio che gli donò la mamma….”(So at once Cacasenno stopped screaming because of a castagnaccio given him by mum…). And finally from Trilussa’s amusing story ”Picchiabbò ossia la moje der ciambellano” (Picchiabbò, the wife of the chamberlain), where Dorotea, the chamberlain wife, whence the title, puts in the soup of King Pepin XVI “un decotto de mosciarelle africane che fa passà la voja de fa’ l’amore a chi se lo beve” (a decoction of African chestnuts that stops wanting to make love to the one who drinks it), odd effect seen the fame of aphrodisiac the chestnuts had in the Middle Age, but perhaps the African ones are different!

Also in painting tht chestnut appears often: as an example we remind two works by Arcimboldo, “Vertumno”, where the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II’s chin is formed by chestnut husks and “Autumn”, where a husk and a chestnut form the mouth of the person.

→ To appreciate the biodiversity within the FAGACEAE family please click here.