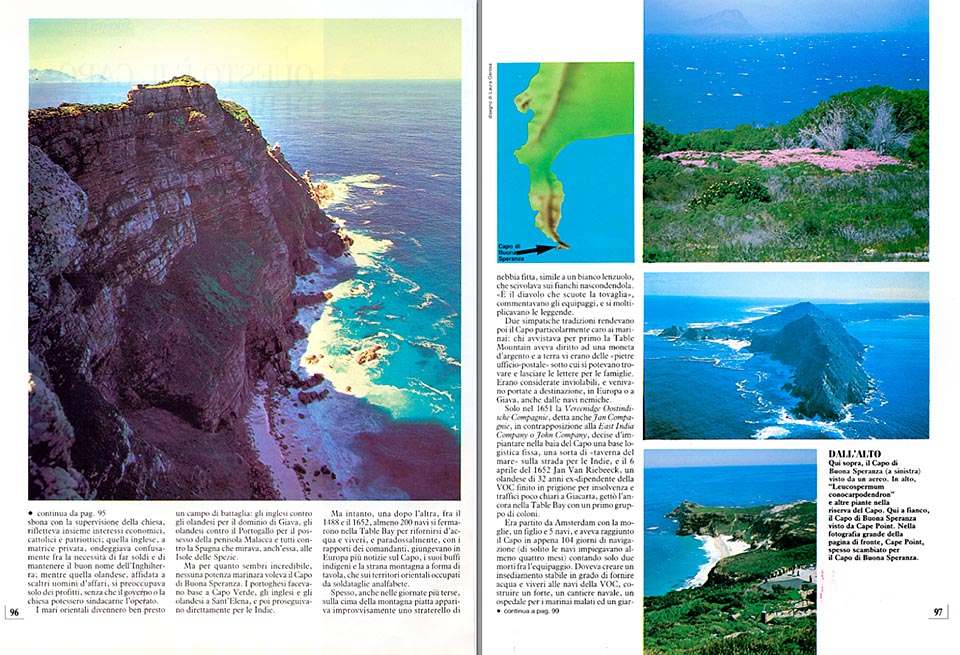

This is the Cape of Good Hope. It is not easy to identify it, and most tourists confuse it with Cape Point. A legendary place and today part of a natural reserve.

English translation by Mario Beltramini

Few areas in the world have roused so many emotions, stories, dreams and confusions, as the Cape of Good Hope.

Still now, many believe that it’s the southern point of Africa, the one which separates the Atlantic from the Indian Ocean, but even if by the two sides of the peninsula, the temperature of the water differs, the Cape of Good Hope is still all entire in the Atlantic Ocean, and the task to separate the two Oceans and mark the extreme south of the continent is fue to the less celebrated Cape Agulhas, about 100 Km. to the east.

Almost all tourists confound it, then, with Cape Point, a big rock overhanging the sea, 2 Km. north-east, which draws at once their attention due to the more imposing appearance and the positioning, compared to the peninsula, which makes it looking more to the south.

The Portuguese navigator Bartholomeu Dias has been, officially, the first one to double it, in January 1488, while trying to reach India. Caught in a violent gale, which carried the vessel to the open sea, he gave the cape, in a first instance, the name of “Cape of storms”. He went on for 600 Km. more to the east, but he was obliged to stop at Algoa Bay, close to the present Port Elizabeth, by a rebellion of the crew members, sick and much worried by the idea of having reached the extreme limit of the known world.

In June, while coming back to Europe, he passed again by the Cape and spent a month anchored in Table Bay, in the lee of Robben Island. Weather was splendid, and he was so much shocked by the beauty of the peninsula, that he decided to rename it as “Cape of Good Hope”.

Still now, it is matter of discussion whether with this name he meant the present Cape of Good Hope, or Cape Point, or the point of Cape Maclear, halfway between the two, where, probably, he landed.

He reported of having left a cross made of rocks on the right spot, but nobody has ever found it. By irony of fate, Dias sank down, only two years later, in a terrible storm just in front of the Cape, but the name of good augury had been already become history.

In 1497, another Portuguese, Captain Vasco de Gama, followed the same itinerary, and while stopping for a week in Table Bay to load water and food, got in touch with the Bushmen, “small brown men”, which expressed themselves with “cracking sounds”. They were gentle and friendly, keen to exchange animals and fruits with the products of the civilization.

Other Portuguese navigators, such as Rio d’Infante, Jaos da Nova, and Antonio da Saldanha, who gave his name to a bay at 100 Km. north of Cape Town, visited thereupon the Cape, and, in 1579, the English Admiral, Sir Francis Drake, denying his stormy reputation, describes the Cape as “the most beautiful in the world and the most impressive thing seen while circumnavigating the world”. A Portuguese dealer, Panteleon Sala, tried also to install there a small base for his trades, leaving a few men ashore. But, once the vessel had sailed, the settlers were immediately killed by the natives.

In 1600, the English founded the famous East India Company for the exploitation of India, and the Dutch, two years later, founded the Vereenidge Oostindische Compagnie (VOC), a mixture of mob of soldiers and merchants without scruples. The colonizing action of the Portuguese, directed from Lisbon with the supervision of the Church, reflected, all together, economic, catholic and patriotic interests, the English, under a private matrix, was confusedly tossing between the necessity of making money and maintain the good reputation of England, whilst the Dutch, entrusted to smart businessmen, was worrying only about the profits, without any control from the government or the Church.

The oriental seas became soon a battle field: the English against the Dutch for the domination of Java, the Dutch against Portugal, for the possession of the peninsula of Malacca, and all of them, against Spain, which was also looking for the Spice Islands.

But, even if it may seem incredible, none of the maritime powers cared of the Cape of Good Hope. The Portuguese had their base at Cape Verde, the English and the Dutch, at St. Helen, and then continued straight to the Indies.

But in the meantime, one by one, between 1488 and 1652, at least 200 vessels stopped in the Table Bay to supply themselves of fresh water and provisions, and paradoxically, with the relations of the masters, arrived in Europe more informations about the Cape, its funny natives, and the odd mountain with the shape of a table, than about the eastern territories, occupied by illiterate soldiers.

Often, even during the most clear days, on the summit of the flat mountain, appeared suddenly a small bank of thick fog, resembling to a white cover, which slipped on the sides, hiding it.

“It’s the devil who shakes the tablecloth”, the crews commented, and the legends did multiply.

Two attractive traditions rendered the Cape particularly beloved to seamen: the seaman who sighted the first the Table Mountain, was entitled to a silver coin, and ashore there were the “Post Office Stones”, under which it was possible to find and to leave letters for the families. They were considered as inviolable, and were carried to their final destination, in Europe, or in Java, even by hostile vessels.

Only in 1651, the Veerenidge Oostindische Compagnie, called also Jan Compagnie, in antithesis with the East India Company, or John Company, decided to set up in the bay of the Cape a fixed logistic base, a sort of “sea inn”, on the way to Indias, and on the 6th of April 1652, Jan van Riebeeck, a 32 years old Dutchman , a former employee of the VOC, who had been previously sent to gaol, in Jakarta, for insolvency and doubtful traffics, dropped anchor with his vessels in Table Bay, with a first group of settlers.

He had left from Amsterdam with his wife, son, and five vessels, and had reached the Cape in only 104 days of navigation (normally, it took to vessels at least four months), with only two casualties among the crew. He had to create a permanent base in position to furnish fresh water and provisions to the vessels of the VOC, build a fortress, a shipyard, a hospital for sick seamen, and a botanical garden where to test, in a temperate climate, the species coming from the Tropics.

Initially, all Europeans who disembarked there, were employees of the VOC, but then the Company thought it was more convenient to discharge them, and buy for them, at fixed prices, wheat, meat and various foodstuff. They became farmers and breeders, and that was the beginning of Cape Town, and of the Colony of the Cape.

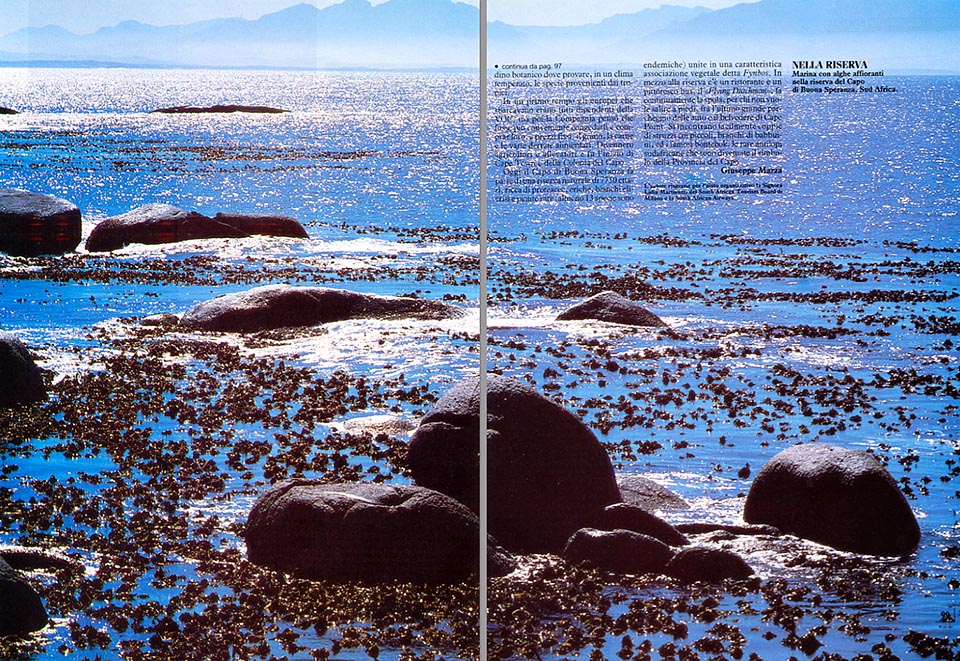

Nowadays, the Cape of Good Hope belongs to a natural reserve of about 7750 hectares, rich of proteaceans, heathers, white helichryisms, and rare plants (at least 13 species are endemic!) united in a characteristic vegetal association, called “Fynbos”.

It is possible to go around by car, and stay under the sun in romantic small clear beaches, surrounded by huge roundish rocks.

In the centre of the reserve, there is a restaurant, and a picturesque bus, the “Flying Dutchman”, goes continuously up an down, for those who do not wish to ascend on foot, between the last big parking place for cars, and the belvedere of Cape Point. It is easy to meet couples of ostrich, with their young, herds of very astute baboons, and the famous Bontebok, the rare south African antelopes, with their odd white-brownish drawing, which have become the emblem of the Cape Province.

© Giuseppe Mazza

The reproduction, even partial, of the text

and the photos without the Author’s written permission is forbidden.