Family : Sphingidae

Text © Prof. Santi Longo

English translation by Mario Beltramini

Acherontia atropos lives in the Afro-tropical and Mediterranean region. The adults’ body is about 7 cm long and the wingspan exceeds 12 cm. Their flight is strong and in a pre-reproductive phase, in the night, they migrate northwards reaching Scandinavia and Iceland. Occasionally they reach Japan and even Mexico © Roger Wasley

The African Death’s-head hawkmoth (Acherontia atropos) is one of the 25 species of European lepidopterans belonging to the family Sphingidae, characterized by adults having a medium or large size, equipped with proboscis or a robust haustellum.

They have a powerful flight and can perform long migrations; some moths, such as Agrius convolvuli or Macroglossa stellatarum, are able to keep flying over the flowers for sucking the nectar like the hummingbirds.

The larvae are “eruciform”, that is with cylindrical body subdivided in little differentiated metameres having soft tegument, with masticatory mouth apparatus, thoracic legs and abdominal false legs. In the eighth abdominal segment there is a characteristic cornet. The tegument is glabrous, wrinkled or warty.

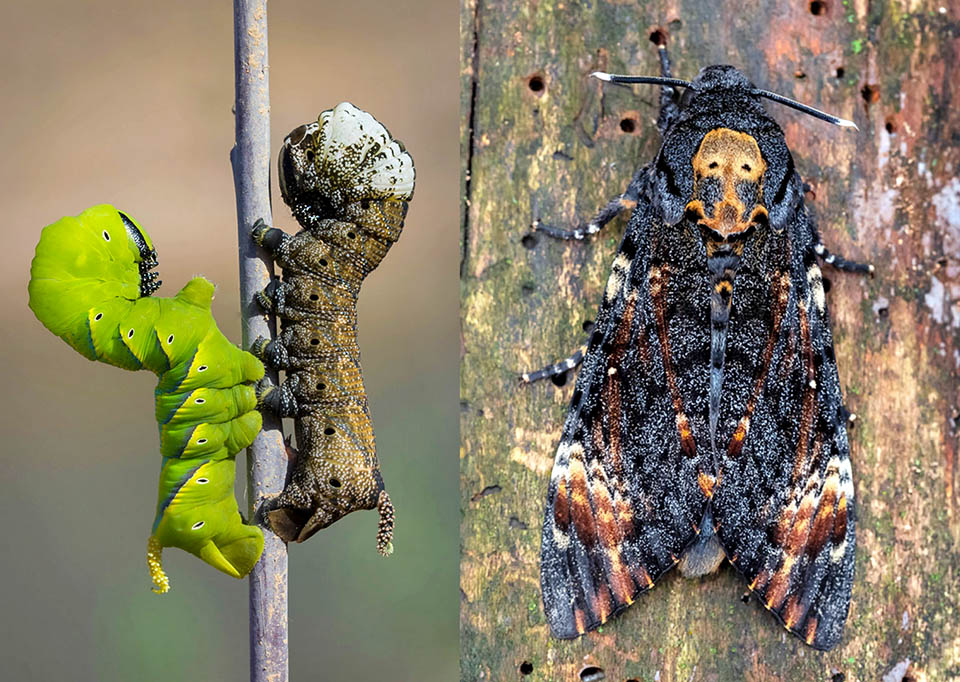

The common name of Death’s-head hawkmoth comes from the clear drawing on the adult’s dark thorax evoking a skull, and from the typical horrifying attitude of the larvae, who for frightening the predators raise head and chest in a position recalling the mythical Egyptian sphinx © Pablo Martinez-Darve Sanz (left) and © Adam Gor (right)

They often try to intimidate the predators assuming a posture defined as “appalling”, raising the head and the thorax that they retract into the abdomen.

The common name of Sphinx refers to the behaviour of the larva that, fixing with its false legs to the substratum, raises the head and the thorax assuming a position that reminds us of the mythical Egyptian sphinx.

In 1758, Linnaeus described Acherontia atropos, as Shinx atropos. Later on, it was transferred to the genus Acherontia, created by Laspeyus in 1809.

During the migrations from Africa to Europe the young adults can enter the hives, tranquillizing the guardian bees with the whistle made by the proboscis that they utilize to hole the opercula of the small cells and to suck the honey. But after having ingested about 10 g of it they are unable to move and are killed and mummified by the bees © Santi Longo

The generic term Acherontia refers to the Acheron, one of the three Hades rivers that, after Greek mythology, were to be crossed in order to enter the kingdom of the dead.

The specific epithet atropos comes from Atropos, name of one of the three Moirai, daughters of the Night, who, in Greek mythology, had the task of cutting the thread of life of human beings.

The epithet “Death’s head” is inspired by the design, present on the black coloured thorax of the moth. It is a classic example of pareidolia, a term with which was defined a subconscious illusion tending to lead to the well-known shape of a skull, the whitish thoracic spots; such instinctive and automatic tendency to find known forms is often associated with human figures and faces.

The eggs measure 1,5 x 1,2 mm and are singly laid on the leaves of the host plants © Paola Michelazzo

Due to the morphological characteristics and the squeak while flying as well as when disturbed, the Death’s-head hawkmoth has evoked ominous symbols.

Pliny the Elder, in his “Naturalis Historia”, cites it as fatal and harmful. In the Middle Ages it was thought that the Death’s-head hawkmoth was a messenger of war and pestilence, bringer of misfortune, able to bring bad lucks and death in the house wherein it was flying and that, its entrance to the church, was omen of serious misfortunes.

Moreover, it was thought that, during the night, the moths could bite fatally the childrens and, in Brittany, they were burnt to mix the ashes in some magic potions.

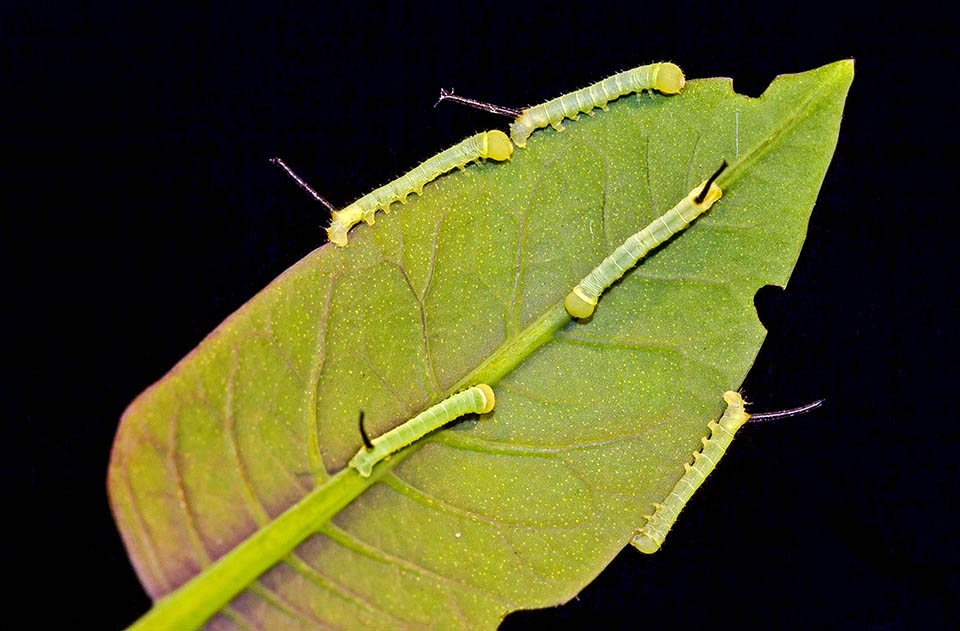

The just born larvae are polyphagous and live at expense of about 40 vegetal species, preferring the spontaneous and cultivated Solanaceae © Pablo Martinez-Darve Sanz

But also in more recent times this moth continued to have a bad name and, in negative terms, has been mentioned in several novels: Acherontia atropos is the fatal protagonist of the poem “The Sphinx” written by Edgar Allan Poe. The Italian poets Guido Gozzano and Eugenio Montale have mentioned its presence deemed nefarious and disturbing.

Also the Asian congener Acherontia styx, quite similar to the atropos, due to the presence of the “death’s head”, enjoys the same bad reputation and, despite that in its place have been utilized chrysalises of the Tobacco hawk moth (Manduca sexta), has been made famous by the movie posters of Jonathan Demme, “The silence of the Lambs”, based on the novel of the same name written by Thomas Harris where the drawing of a skull on the thorax has been replaced by an artistic photo realized by the surrealist painter Salvador Dali’ and by Philippe Halsman who have depicted from 7 nudes of women.

Second age grown larva with the characteristic tiny spines on thorax. Besides tomatoes and potatoes, it can attack arboreal or shrubby species like the olive tree and vine © Frank Schneider

Zoogeography

The Death’s-head hawkmoth is permanently present in the Afro tropical and Mediterranean region, is diffuse in the Canary and Açores Islands, in the southern zone of the Mediterranean Basin, up to the Arabian Peninsula. From these areas, starting from spring and during the summer, the adults in the pre-reproductive phase, during the night, migrate northwards going as far as Scandinavia and Iceland. Occasionally, they reach Japan and even Mexico.

Ecology-Habitat

Like numerous other species of Sphingidae, in the young adults of Acherontia atropos, is found the so-called “migratory syndrome” that involves complex interactions, the flight, the reproduction and the feeding, pushing them towards new environments.

Third age larva. The colour may be clear or dark and the two forms are often found on the same plant © Pablo Martinez-Darve Sanz

In southern Italy the larvae are present, in summer-autumn, on Solanaceae, cultivated and spontaneous, on the Olive and on other arboreal plants.

In winter some adults introduce themselves in the hives, without, however, causing any important damage, as can instead be seen in Africa, where the frequent massive presence of moths, represents a problem for the traditional beekeeping.

Morphophysiology

The adults’ body is about 7 cm long and has a wingspan of more than 12 cm.

In the head, the antennae and the eyes are well developed, and is present a short and robust haustellum (proboscis), from where, if distubed, the moth emits a mournful squeak.

Multicoloured fourth age larva on branch. Usually they don’t cause remarkable defoliations due to the low population density and the very high mortality for natural causes © Paola Michelazzo

The hairy thorax is black with white spots.

The forewings are long and narrow, have a brownish background colour with sinuous transverse pale and dark grey stripes with at the centre a small clear discal spot. The back wings have the background of yellow colour with two wide brown transversal bands.

On the mesothorax is present the spot whose shape reminds that of a human skull. The abdomen, big and hairy, narrowed towards the final part, is yellow with blackish transversal bands.

The eggs, oval in shape, measure 1,5 x 1,2 mm, are blue-greenish or greyish coloured, and are laid singly on the leaves of the plants on which the larvae feed, that the female locates thanks to its numerous sensory organs (gustatory sensilla).

Larva seen from the front to emphasize the robust chewing mouthparts, the six legs and one false leg © Adam Gor

The newly born larvae, 5 mm long, are of pale green colour; those of the typical form, become darker and darker, highlighting the lateral yellow bands; on the dorsal part of the eighth abdominal segment is present a characteristic hornet brown and smooth.

The second age larva presents dorsally some tiny spines. During the two following larval stages, the diagonal yellow bands present blue or violaceous margins; the hornet, yellowish, presents small granules.

The fifth and last age larvae, up to 15 cm long, are usually of yellow and green colour with dark oblique bands laterally edged with yellow; the back, without spines, is light blue in colour.

Less common are the forms of brown colour and clear thorax, that are interpreted as cryptic mimetic colours for escaping predators.

The pupa, that in the lepidopterans is called chrysalis, is 5 to 8 cm long with reddish brown coloured tegument, more or less dark, protected inside a small cell dug into the ground by the mature larva (eopupa).

Ethology-Reproductive Biology

In the southern environments of the Mediterranean, it carries out up to three annual generations and winters in the ground at the stage of chrysalis.

The larvae are polyphagous and live at the expenses of about 40 vegetal species afferent to 24 botanical families, with a preference for the Solanaceae, spontaneous and cultivated (tomato, aubergine, potato, tobacco, datura); they are found often on arboreal and shrubby plants (olive tree, vine, oleander, apple tree, elderberry, ash tree).

Usually, they do not cause appreciable defoliation in relation to the low density of population and to the extremely high death rate due to natural causes.

Based on the thermal trend, the larva may complete its development in about one month. From the chrysalises that succeed in surviving the winter, the adults flutter starting from the month of April.

During their nocturnal migrations, carried out isolated or in small groups, the adults can accidentally go out to the open sea, attracted by the lights of ships on which they land to rest.

Fifth age larvae. The first eats a poisonous Datura whilst the other looks sated, mimicked among branches. Death’s-head hawkmoth may have three generations in a year © Adam Gor (left) and © Africa de Sangenís (right)

Some specimens have been caught even at a few hundred miles off the coast.

With its short, sclerified and pointed proboscis, it is able to eat into, besides the opercula of the small honey cells, also the peel of ripe fruit. Many moths are attracted by the smells of hives and, often, do enter them emitting a squeak similar to that of the queen bee.

It is thought that such a sound, consisting in two brief sequences repeated rapidly: one low toned, sue to the dilation of the pharyngeal cavity, that makes vibrate a prominence of the palate, and a sequence of high tone due to the expulsion of the air along the short proboscis that works like a whistle, serves to calm down the bees, allowing the moth to take off, not disturbed, the honey of the opercular cells after having holed them with the short and robust proboscis.

Fifth age mature larva that has ceased feeding and becomes torpid, it is called eopupa © Giuseppe Sartori

Moreover, it is thought that the moths camouflage chemically producing from the glands tegument, fat acids similar to those present on the body of the bees.

After having ingested a quantity of honey of about 10 g the worker bees kill the moth now unable to move, and mummify its bulky body with the propolis; the reaction of the guardian bees begins when the moth, now filled to satiety, is unable to emit any screeching.

In our environments the damages caused by the adults to the hives are absolutely negligible whilst in Africa they are often considerable in the honeycombs whose entrance fissure is not properly protected by grids that prevent the entry of the large adults.

The mortality for natural causes of the various stages of development of Acherontia atropos is high.

At this point it drops to the soil and looks for suitable site where to dig the pupal cell where metamorphosis will occur © Ge van ‘t Hoff

The adults’ mimetic colouration ensures a partial protection from predators during the day: also the sound emitted has a prevalent defensive function as, united with the raising of the wings, the rapid movement of the abdomen, of yellow colour, and with the secretion of of substances having a nauseating smell from the abdominal glands, often discourage the predators’ attack.

The main causes of mortality of the preimaginal stages are: bacteria, fungi and entomopathogen viruses, as well as several endoparasitic insects: among the Dipterians are reported Compsilura concinnata, Masicera pavoniae and Winthenia rufiventris, the most frequent in Sicily is Sturnia atropivora, whose gregarious larvae develop and transform in pupa in the body of the host but flicker from the chrysalis of the Sphinx.

Active are also the parasitoids ichneumon hymenopterans Amblioppa fuscipennis, Amblioppa proteus, Callajoppa cirrogaster, Callajoppa esaltatoria, Diphyus longigena, Diphyus palliatorius, Ichneumon cerinthius and Netelia vinulae.

A chrysalis inside the artfully opened earth cell. 5-8 cm long, it has the tegument of brown reddish colour, more or less dark © Pablo Martinez-Darve Sanz

Synonyms

Sphinx atropos Linnaeus, 1758; Atropos solani Oken, 1815; Acherontia sculda Kirby, 1877; Acherontia conjuncta (Tutt, 1904); Acherontia extensa (Tutt, 1904); Acherontia flavescens (Tutt, 1904); Acherontia imperfecta (Tutt, 1904); Acherontia intermedia (Tutt, 1904); Acherontia obsoleta (Tutt, 1904); Acherontia suffusa (Tutt, 1904) Acherontia variegata (Tutt, 1904); Acherontia virgata (Tutt, 1904); Acherontia violacea (Lambillion, 1905); Acherontia charon (Clos, 1910); Acherontia diluta (Closs, 1911); Acherontia obscurata (Closs, 1917), Acherontia myosotis (Schawerda, 1919), Acherontia confluens (Dannehl, 1925); Acherontia moira (Dannehl, 1925); Acherontia pulverata (Cockayne, 1953); Acherontia radiata (Cockayne, 1953); Acherontia griseofasciata (Lempke, 1959).

→ For general notions about the Lepidoptera please click here.

→ To appreciate the biodiversity within the BUTTERFLIES please click here.