Family : Bovidae

Text © DrSc Giuliano Russini – Biologist Zoologist

English translation by Mario Beltramini

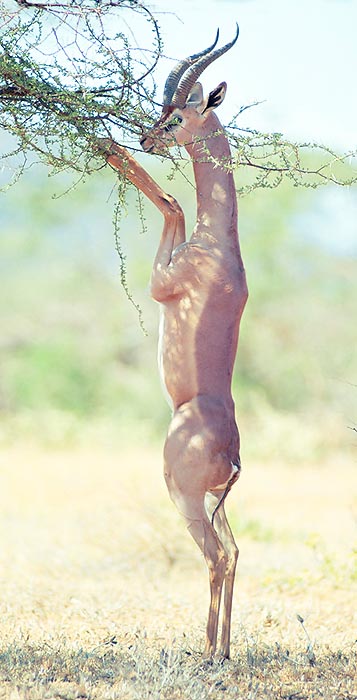

The Litocranius walleri lives in very dry zones © Giuseppe Mazza

The Litocranius walleri Brooke, 1878, commonly called in Somali “gerenuk” or “gherenuc”, which means Giraffe-necked Antelope, and in Swahili “swala twiga”, that is Gazelle Giraffe, is an eutherian (placental) mammal, quadruped, belonging to the order of the Artiodactyla, and to the family of the (Bovidae).

Endemic to eastern and southern Africa, it was discovered in 1878 by the English biologist and zoologist Sir Victor Alexander III, baronet of Brooke. He was an anthropologist too, and his interest for the indigenous peoples took him several times to Africa, especially in the eastern and southern one, where he discovered this odd animal. He describes it to us, along with other species of gazelles and antelopes, in his imposing opus “The Book of Antelopes”, unachieved due to his demise, and completed between 1894 and 1900 by the zoologist and biologist Philip Sclater and the ethnologist and biologist Oldfield Thomas, his former pupils.

The Litocranius walleri is a particularly shy species, difficult to be found, frequently hiding in the bush. But it has always been remarked thanks to the elegance of its movements, and, since the ancient times, it has stricken the human imagination. Traces of it are found in many paintings of Egyptian tombs dating from the 5600 B.C. and, ethno-biologic curiosity, many tribal populations, such as those of the former British Somaliland or the Maasai from Kenya, thinking that it comes from the crossing of a giraffe with a camel, do not venture in killing and eating it, as they are afraid to wake the rage of the spirits, which, for avenging, would cause epidemic diseases among their camels and dromedaries.

Zoogeography

The Litocranius walleri are endemic to eastern and southern Africa, Somali, Kenya and Tanzania, but can be found also in Ethiopia. Their population is presently under risk of extinction, due to the crazy intensive hunting of the touristic safaris of the past times. Most of its members are nowadays confined in the Samburo National Reserve, a park in Kenya where the biologists of the IUCN control and maintain the population, through programmes of conservation and of reproductive biology.

Habitat-Ecology

The Litocranius walleri have adapted to live in small groups, mixed, of males and females, which do not exceed the 10 specimens, in particularly arid areas of the Africa bush, covered by xerophilous (adapted to drought), shrubby and often thorny plants. And when they get scared, odd thing, instead of running away or defend themselves, both females and males have the tendency to hide their head in these thorny shrubs.

It can nibble, standing, the high branches of the trees © Mazza

Like the gazelles of the genus Oryx, as they live in particularly dry habitats, they have developed, as eco-physiologic strategy, the capacity of watering with the morning dew present on the leaves they eat. That is sufficient for their daily water needs and can therefore keep without drinking, even for months, associating to this ecologic strategy, the tendency to urinate very little in frequency and volume, with a hypertonic urine (very thick and containing little water) and defecating only the least necessary, with very compact and deprived of water bowels.

Thanks to the great agility characterizing them, usually they do not have many predators: mostly Cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus) or Lions (Panthera leo), especially females.

Another oddity, connected with the habitat they live, is the capacity to nourish of the tall branches of the trees, contrarily to the most of the gazelles and antelopes which look for the food on the ground. They lean their long and thin fore legs to the boughs, especially of Acacia tortilis, and nibble in every direction, with their long neck, balancing on their robust back limbs.

Morpho-physiology

The males and females of Litocranius walleri usually have the same size: 50-52 kg of weight, 100-110 cm at the withers, per 140-160 cm of length, to which we have to add 25-30 cm of tail, which ends up with a tuft of black hair. The sexual dimorphism stands in the hollow horns, thick and decorated with rings, lyre-shaped, present only in the males. Their length can vary from 25 to 30 cm.

Both sexes have a fulvous coat along the body, the sides and the back quarters, with a toning to the reddish on the back, whilst the belly and the hinders are white. The skull is brachycephalous (short and flat), followed by long and thin muzzle which allow the animal to creep into the shrubs. The auricles of the ears are pronounced in respect to the skull and lance-shaped, placed on the sides. The have inside a black down, which forms a particular drawing.

The eyes, with white circled orbits, have a dark iris, are great and suitable for a sharp eyesight. This sense, with the smell, is in fact very developed in the Litocranius walleri. Obviously, they are ungulates, like all Bovidae, with spurs similar to osseous excrescences, placed up, at femoral level, in the back limbs.

The most prominent anatomical characteristic, which justifies the common name of Giraffe-necked Antelope, is, however, the presence of a neck long even more than one metre, suitable for reaching the leaves of the trees. In the females this is little thinner than in the males, where it swells more during the heat season. A visual sexual mark for the females in oestrum, and a harmonic case for the specific and characteristic cries.

Ethology-Reproductive Biology

The female has a bicornuate uterus, with cotyledonal, syndesmochorial placenta. Pregnancy is usually 165 days long, about five and a half months. The deliveries are single. The new-born is already able to walk a couple of hours after the birth, and begins to suckle. It usually remains five months with the mother, and then is weaned. The young, united in small semi-nomad groups of specimens of the same sex, are by that time much exposed to the preying of the carnivores, which in this way strongly level the density of population of the species.

By September, during the heat season, the males, which, like the females are usually shy and bashful, must form their harem, and since they are characterized by a promiscuous sexual behaviour, they often become aggressive. They begin to mark the soil with the odoriferous glands placed at the base of the limbs, and the shrubs with the supra-orbital ones. A territory can host even 10 females forming the harem. The lacrimal glands become very active and produce an odorous liquid, which the males smear reciprocally on the muzzles, for recognizing the hierarchical position.

When a dominating male feels the presence of a competitor, an ethologic ritual begins, with puffs and with shakes on the ground of the limbs and the horns. If nobody gives up, the physical fight takes place, with butts, kneeling on the fore limbs, until the wounds will manifest the winner.

→ For general information about ARTIODACTYLA please click here.