Text © DrSc Giuliano Russini – Biologist Zoologist

English translation by Mario Beltramini

Simpson classification (1973) of Artiodactyla.

A Litocranius walleri grazing in acrobatic position © Giuseppe Mazza

►Suborder Suiformes:

-Family Suidae

-Family Hippopotamidae

-Family Tayassuidae

►Suborder Tylopoda:

-Family Camelidae

►Suborder Ruminantia:

-Family Amphimerycidae extinct

Infraorder Tragulina

-Family Prodremotheriidae extinct

-Family Hypertragulidae extinct

-Family Praetragulidae extinct

-Family Tragulidae

-Family Leptomerycidae extinct

-Family Archaeomerycidae extinct

-Family Lophiomerycidae extinct

Infraorder Pecora

-Family Moschidae

-Family Cervidae

-Family Giraffidae

-Family Antilocapridae

-Family Bovidae

The Perissodactyls (Perissodactyla) form, at the beginning and at the end of the Tertiary,as we have seen, an important and varied group, but now close to extinction. Quite different is the natural history of the order of the Artiodactyls (Artiodactyla), called also ungulate even-digitigrades. They were rare at the beginning of the Eocene, but during the Tertiary they rapidly increased the number of the species and of individuals and it seems that they are now in the moment of their maximum evolutionary development; in fact, they include forms such as the pigs, the peccaries, the hippos, the camels, the llamas, the deer, the giraffes, the bovines, the sheep and the goats, not to talk about the endless line of the antelopes and the gazelles.

The term “artiodactyls”, even-toed, comes from a particular reduction of the number of the toes, within this order.

Kobus kob thomasi. Due to the special form of the astragalus the Artiodactyla have an outstanding width of movements in the hind limbs © Giuseppe Mazza

If the perissodactyls, for the majority, have reduced the number of the toes from five to three, the artiodactyls have on the contrary lost, quite early, the thumb and the big toe, but have had the tendency to keep, at least for a certain time, a limb with four toes, where the third and fourth toes tended to form a prominent central pair, whilst the second and fifth one flanked the earlier ones on the sides.

A further progress may come, as did often happen, from the reduction and often the loss to the two lateral toes, with the formation of what is called the “goat’s foot”, formed in reality, by two very close toes.

Even toed, pigs, more omnivorous than herbivorous, still have 4 of them © G. Mazza

Another distinctive character of the artiodactyls concerns the adaptation to the fast running, and involves a bone of the ankle, called “astragalus”.

This bone forms the main articulation between the leg and the foot. In most mammals the upper surface is curved, often shaped as a pulley, for allowing the movements, whilst the lower surface is flat.

In the artiodactyls and only in this animal group, the upper surface of the astragalus as well as the lower one are rounded forming a pulley, and thus allow an exceptional extent of movements for the hind limb, in the run and also in the jump.

The oldest artiodactyls of the Eocene show few evolutionary changes (excepting the characteristic astragalus), in relation to the lower ungulates of the level of the (Condylarthra).

But, before the end of this epoch, there was the start of a change we observe to develop in forms evolving in opposite directions.

In one of the main branches of the evolution of the artiodactyls, the teeth tend to keep the low crown, with rounded cuspids, for an omnivorous diet.

The pigs, typical members of this group, appear, with similar forms, in the fossiliferous strata of Eurasia by the end of the Eocene. They still have four toes on the paws, even if the lateral pair is reduced. They have an omnivorous diet, more properly, herbivorous; the canines are well developed and have the shape of a fang, usually curved outwards and even upwards, on the two sides of the snout.

The properly so called pigs, are animals which belong solely to the Old World and have never reached the Americas, where, on the contrary, we find a similar branch coming from the same line: the peccaries.

Also hippos are artiodactyls but after some they are related to cetaceans © Giuseppe Mazza

They resemble to the pigs, but have a more slender look and, even if their fangs are prominent, these do not have the particular bending the pigs have.

The peccaries have lived, for the major part of their natural history, in North America and lived also in the Pleistocene, during the Quaternary, the regions not invaded by ice in this part of the continent.

However, in the Pleistocene, they entered South America and presently they do live in the tropical and subtropical zones.

For instance, the Collared peccary (Dicotyles tayassu), up to 46 cm, is one typical member.

This animal is smaller than our home-grown boar Sus scrofa and frequents, in crowded groups, the tropical and subtropical South American pluvial forests.

They are harmless if not attacked, otherwise, they may reveal dangerous also for the man; they belong to the choice preys of the Jaguar (Panthera onca) and of the Anaconda (Eunectes murinos).

During the Tertiary period, there was the development of a certain number of the suiforms, animals similar to the group pigs-peccaries, of which the only survivors are: the well-known Hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius) and the Pigmy hippopotamus (Choeropsis liberiensis); stocky animals (the second one smaller than the first), both amphibious and presently confined in the western sub-Saharan Africa, but, in the Pleistocene, present up to Eurasia, where they lived in regions far from each other, such as England and China.

Teeth are also a weapon in the hippo and the warthog © Giuseppe Mazza

In fact, the geneticists tell us nowadays the hippos should be more strictly related to the order of the Cetaceans (Cetacea), than with the group of the suiforms.

Basically, it appeared that, like the dolphins come from a terrestrial carnivorous progenitor, by living an increasing amount of time in the water, has, in geological times, regained the ability to live their permanently, generating the dolphins, there is perhaps a relation of this type also between the hippos and the cetaceans, more specifically with the suborder of the Mysticetes (Mysticeti); some authors inform us that it would be useful to introduce the superorder of the Cetardiodactyls (Cetartiodactyla) thing which would resolve the paradox; to the taxonomists the last word.

The hippos in the strict sense, are unknown before the end of the Pliocene; the scientists, who persist on a strictly terrestrial existence of these animals, hypothesize its derivation from a prehistoric group of big suiforms, the Anthracotheres (Anthracotheriidae), from which, after other paleontologists, should come also the whales, reason why hippos and whales should be cousins, somewhat like for the human being and the anthropoid apes leading to the family of the Pongids (Pongidae). The anthracotheres date, especially in the Old World, from the late Eocene.

In addition to the forms just cited, almost all the other groups of artiodactyls, from the end of Eocene onwards, have had a tendency to evolve in completely different way.

The general directions of these lines was to acquire and exclusively herbivorous diet; this meant teeth often without high crown (hypsodonty) and crescent-shaped cuspid, and for this reason also the wording “selenodonts”, able to chew efficaciously the most coriaceous vegetables; a stomach divided in compartments or chambers which allows the rumination, necessary for a better digestion of these aliments; finally, in most of the cases, a tendency to acquire a capacity of movement with more slender limbs and reduced lateral toes.

Several species of artiodactyls have progressed, more or less, along these lines of evolution. As an example of a group which has manifested an evolution rather limited in this direction, we mention that of the Oreodons (Oroeodontidae), of North America which, anyway, were able to thrive for a significant period during the Tertiary and which are the most common fossils, in most part of the formations of the Oligocene and the Miocene of that continent. They are often called, failing a more appropriate common term, the “ruminant pigs” as the proportions of their squat body are similar to those of the pigs, but the teeth of selenodont type, betray a kinship with the more evolved ruminants.

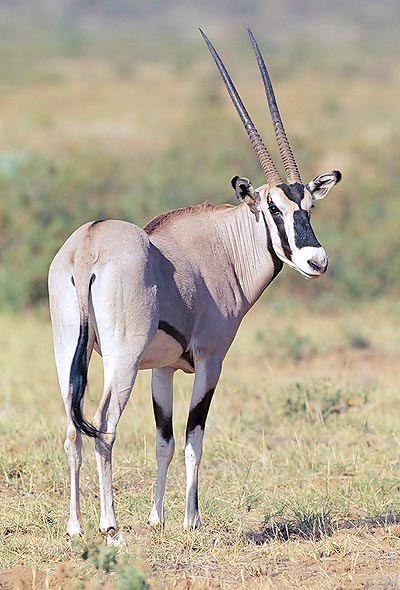

But defence, as for oryx, is usually left to the horns © Giuseppe Mazza

A second characteristic American group is that of the camels, suborder Tylopods (Tylopoda).

Presently, no representative of this suborder, family of the Camelidae, lives in North America; the camels are limited to the Old World, with the Asian species of Camelus bactrianus and the North African one of Camelus dromedarius, whilst the llamas and kindred forms, such as the vicuna, the alpaca, the guanaco, all wild, are confined, except for the farms, in South America.

In these animals, the stomach is partially subdivided like that of the ruminants (see texts about Bos taurus, Camelus bactrianus, Camelus dromedarius and Lama guanicoe); the teeth are selonodonts and the lateral toes are missing at the extremities of the limbs.

The morphological characteristic which has led to the name of the suborder is the presence of callused soles on which the foot rests; these permitted the deambulation on soft grounds such as the sandy ones of the deserts.

The predecessors of the camels did appear in North America around the early Oligocene; a huge variety of camels did exist in America, where they were confined, by the end of the Tertiary.

In the Pleistocene, the camels migrated towards the Old World and the ancestors of the llamas, of the alpacas, the vicunas, the guanacos, did move towards South America.

At the end of the Pleistocene, in North America, the camels disappeared just as suddenly and mysteriously as the horses.

The main evolutive line leading to the present forms of more evolved ruminants seems to have originated in the Old World, rather than in the new one.

In most of these more evolved forms, to which often is given the common name of ruminants, infraorder Pecora, the subdivision of the stomach in chambers is complete and the rumination is general; they usually have simple and ramified horns, depending on the species; the lateral toes are reduced, even, if some traces of them may remain under form of small “sessile” protuberances, adherent to the tissue; the long bones which that are placed in the upper portion of the foot, unite in one unique bone, the “cannon bone”; the front teeth of the upper jaw (the incisors), disappear.

Dromedary (Camelus dromedarius), Sheep (Ovis aries), Cow (Bos taurus) and Llama (Lama guanicoe) had an important role in man’s history © Giuseppe Mazza

The primitive forms which led to the present ones, more evolved, appear in the Eurasian Oligocene. Their direct descendants, still extant presently, are the small Tragulids (Tragulidae), of the Old World Tropics. Slightly larger than a hare, they have all the appearance of a miniature cervid, but do not have horns and are more primitive than the true and proper ruminants, for various characters, among which the retention of lateral toes, complete even if small. The real ruminants have developed in four families: two have conserved the ancestral habits and have remained in the forests nourishing of leaves and sprouts, and two have become grass-eaters, in the open plains.

Cervus elaphus male bellow. The full antlers fall each year © Giuseppe Mazza

Among the first two families, the most diffused is that of the Cervids (Cervidae.) The other family of the leaves-eating ruminants is that of the Giraffids (Giraffidae).

Indeed, some taxonomical biologists consider a third family of ruminants having adopted this diet, which is that of the Moschids (Moschidae); other scientists still insert it, inserted it, in the Cervidae, to which leads one unique genus Moschus, considered as a more primitive cervid.

Going back to the Cervidae, this family originated from an ancestral group of primitive ruminants known since the Tertiary; by the end of the Miocene, the real cervids began to appear, spreading in all Eurasia and finally reaching the Americas.

The cervids, still eaters of leaves, have maintained teeth with low crown. Some small cervids have no horns, but most of them have acquired organs called horns or antlers, which are really bony ramified excrescences of the front, covered during their growth by the “velvet”, a delicate skin, in its turn covered by a thick down.

In the cervids, these horns are present only in the masculine specimens (seasonal-transitory sexual dimorphism character) and are subject to a cyclical loss and regrowth, made by the androgen hormones, which, in turn, are cyclically secreted by the testicles, as an effect of the alternating of the seasons and lead the reproducing male to come into oestrus with the arrival of the spring. The scheme is the following: each year, once the sexual maturity is reached, the males mount the antlers during the winter season, when they are making solitary and secluded life from the herd. Every year, the horns are increasingly ramified, as a new point comes out close to a node. One year more of age corresponds to each of these ones.

Family group of cheetals (Axis axis). Clear sexual dimorphism © Giuseppe Mazza

When the spring approaches, these antlers, which in the Red deer (Cervus elaphus) may reach, in the oldest specimens, even the five metres of length, lose the velvet covering them and may be therefore utilized for fighting with a competitor for contending a female in oestrum.

But the whole thing takes place through more or less ritualized fights, accompanied by strong roars.

Once the winner has mated, it leaves the herd to which it had come back, as the other males, for reproducing.

Now the antlers are no more necessary, on the contrary, they become an obstacle for getting back to the isolated life in the wood, far away from the herd. They will fall quite soon and the same cycle will repeat by the following year.

It is therefore easy to find, in the woods frequented by the cervids, the velvet covering the antlers, as well as their remains.

These horns, being full, lead to define these animals as “plenicorns”.

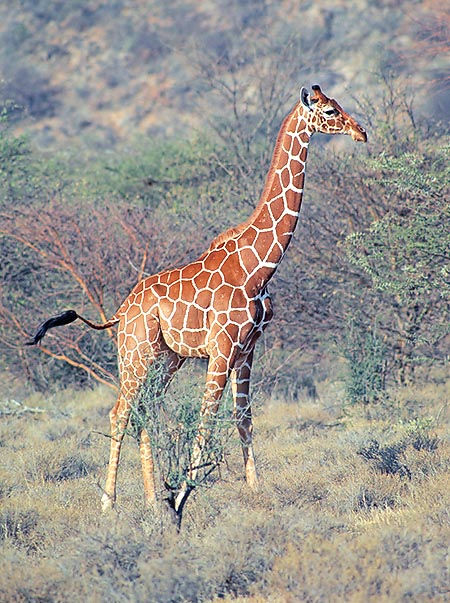

As I was mentioning before, the second family of the leaves eating ruminants is that of the Giraffids (Giraffidae), native, also this one, to the Old World, where has remained confined in the African continent. Of course, the most known form is the Giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis), with all its races or subspecies and the varieties, in relation to the mantle and the origin place. As it can be seen from the fossils, this group is not clearly distinguishable, before the Pliocene, from the other ruminants.

The giraffe is a leaves-eating ruminant © Giuseppe Mazza

The giraffe, the tallest land mammal, nourishes of the leaves and the buds of the trees, in particular of the Fabaceae, such as the Acacia tortilis, taking advantage from its long neck and the long hind legs on which it stays, that get it reaching the remarkable height of six and more metres, per a weight of two tons.

Since the late XIX century, as we know, there were rumours (from legends of the Negrillo Pygmies Aka/biaka who lived, and still live, in the virgin forests of the Republic of the Congo and of the Central African Republic, in Central Africa) about the existence of what was called the horse of the pigmies.

The American zoologist, journalist and explorer Sir Henry Morton Stanley, listening to these reports, during one of his expeditions in 1888-1889, discovered some skins which were leading to this mysterious and legendary animal.

He sent these skins to Oxford, to the director of the Natural History Museum, the zoological biologist Harry Johnston, who confirmed that they were not a fake.

The Oxford zoologist then decided to find, with a scientific expedition, this cryptic animal and in 1902 seized the first specimen of what turned out to be a second species of Giraffidae, the Okapia johnstoni.

This second giraffe, smaller, is a form more similar (therefore more archaic) to the extinct types.

Both species have small horns in different number, called “exostoses”, that are actually small bony excrescences covered by hairs, placed on the head; however, some ancestral extinct representatives had them, but ramified.

Among the two families of grass-eating ruminants, the Antilocapridae and the Bovidae, the first, less important, has evolved in North America. The only extant member of this family is the Antilocapra, or Pronghorn or American antelope (Antilocapra americana), which lives in the plains of the West. This lovely animal has, like the members of the parallel group of the Bovids (Bovidae) of the Old World, teeth with high crown, suitable for the mastication of the grass.

The Okapia johnstoni is kin to giraffe, discovered in 1902 only © Giuseppe Mazza

The horns are of a particular type: inside there is a bony point which, like for the bovids, is permanent and not caduceus; not ramified as well.

This bone is covered by a sheath made by real corneous substance, partly bifurcate, which, contrarily to the bovids’ horns, falls every year.

The pronghorn is therefore a sui generis typical American animal, which refuses to integrate in the characteristics of the other members of the group of the universa Pecora.

The first members of this group of antilocaprids did appear in the Miocene, when abundant prairies developed for the first time.

A certain number of genera of this family abounded in the American prairies around the end of the Tertiary and also in the Pleistocene, Quaternary; the reduction of the group to only one surviving species is due, most probably, to its unique ability to resist to the concurrence of the American bison (Bison bison), Pleistocene invader coming from Asia, which spread in huge herds in the American prairies, with millions of heads, from the end of the Pleistocene up to the first half of the XIX century.

The last and most important ruminants family, and therefore of the ungulates, is that of the Bovids (Bovidae), presently including not only the bovines of the genus Bos, but also the Bison, American (Bison bison), as well as European (Bison bonasus), the Musk ox (Ovibos moschatus), the sheep, the goats and a multitude of other animals, differing from each other, usually grouped under the name of “antelopes”.

The North America Bison (Bison bison) is on the contrary a typical grass eater © Giuseppe Mazza

These last, in the Old World, are the herbivores corresponding to the pronghorns of the New World; but they have had a much ampler evolutive and radiative success.

The typical character of the bovids is the presence of horns which, contrary to the cervids, do not fall and are hollow, reason why these animals are defined as “cavicorn”.

Like the pronghorns of North America, the grass-eating bovids appeared in the Miocene at the same time of the prairies.

They had increased remarkably in the Pliocene, in number of species as well as of individuals, and some tens of forms of antelopes did abound in the plains of Europe and Asia.

Following the Pleistocene glaciations, they greatly decreased in number in the northern regions and, rightly, it is in the African plains that we must look nowadays for these bovids, in the full evolutive splendour, under form a great quantity of species, still much numerous despite the ruin the man has always induced, through the hunting, the pollution and the agriculture.

The Arctic artiodactyls musk oxen have adapted to the polar coldness.

Except for these last, only few bovids have reached the New World; these are animals capable to live in rather clod climates, like the wild sheep of Alaska and of the Rocky Mountains, the snow goats and the bison, that, having reached America during the interglacial period of the Pleistocene, rapidly populated its plains.