The rich relatives of Myrtle. The exotic relatives of our myrtle. Big trees and shrubs with flowers like pompon, feathers and cleaning brushes. Edible fruits.

Text © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

If, leaving the coast, you reach a whatever inner point of our seaside for a walk in the shrubbery or the garrigue, between the brooms, the rock roses, the mastics and the wild rosemary, you will by sure find the myrtle (Myrtus communis).

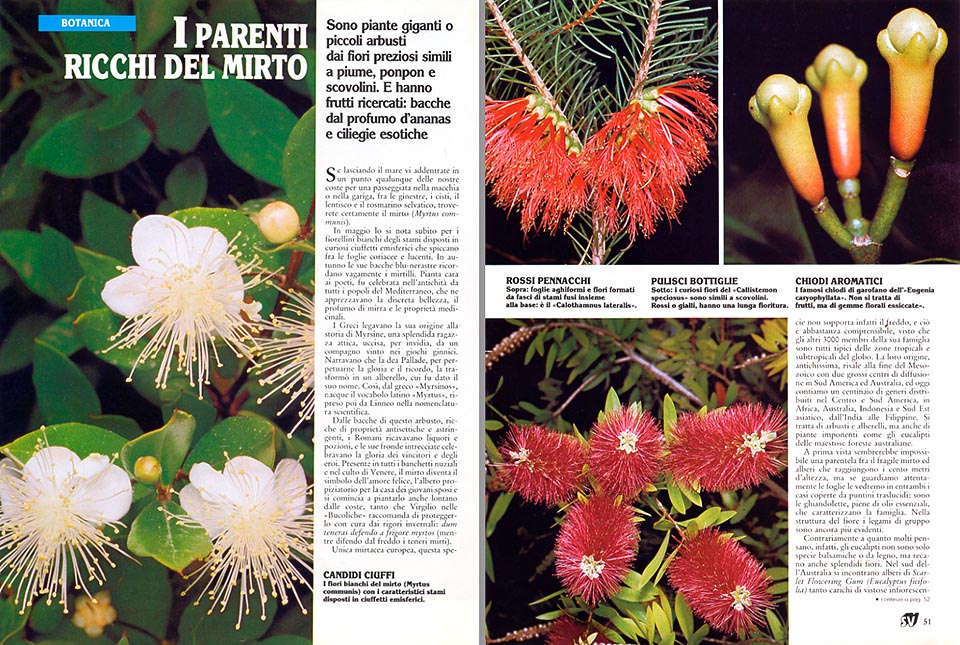

In May, it’s immediately noticed for the white small flowers with the stamens ranged in odd hemispherical small tufts which show up between the tough and bright leaves. In autumn, its blue-blackish berries recall, vaguely, the blueberries.

Plant loved by poets, was celebrated, in the old times, by all the peoples of the Mediterranean, who appreciated its discreet beauty, the scent of myrrh, and the medicinal properties.

The Greeks associated its origin to the story of Myrsine, a splendid Attic girl, killed for envy, by a companion defeated in the athletic games. They were narrating that the goddess Pallas, in order to immortalize her glory and memory, did transform her in a sapling, which was christened after her name.

So, from the Greek “Myrsinos”, came the Latin wording “Myrtus”, taken later on by Linnaeus in the scientific nomenclature.

From the berries, rich of antiseptic and astringent properties, the Romans were obtaining liqueurs and potions, and its foliage, pleached, celebrated the glory of the winners and of heroes.

Present in all wedding banquets and in the worship of Venus, the myrtle becomes the symbol of happy love, the propitiatory tree for the house of the newly-married couples and they start to plant it also far away from the coasts, so that Virgil, in the Bucolics, recommends to protect it with care from the rigours of winter, “dum teneras defendo a frigore myrtos”.

Sole European myrtaceae, this species does not stand, in fact, the cold, and this is quite understandable, as the other 3.000 members of its family, are all typical of the tropical and subtropical areas of the world.

Their origin, very old, dates back to the end of the Mesozoic, with two vast centres of diffusion in South America and Australia, and nowadays we count about one hundred genera distributed in Central and South America, Africa, Australia, Indonesia, and South East Asia, from India to Philippines.

It’s matter of shrubs and saplings, but also of imposing plants such as the eucalypts of the grand Australian forests.

At first sight, it would seem impossible a relationship between the brittle myrtle and trees which reach the 100 metres of height, but if we look carefully at the leaves, we see that, in both cases, they are covered by translucent small dots: the small glands, full of essential oils, which are characteristic of the family.

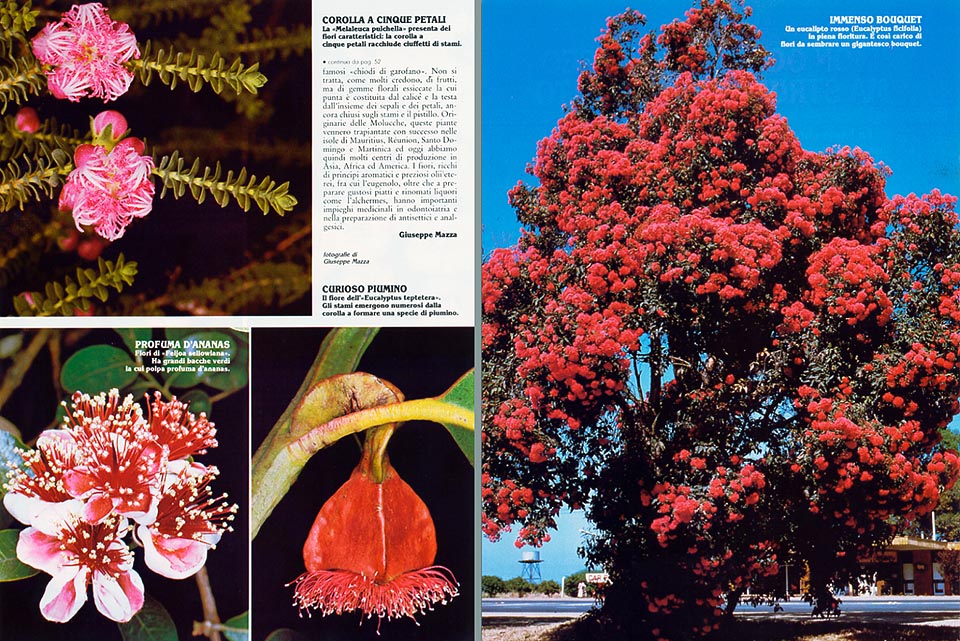

The group links are even more evident in the structure of the flower. Contrarily to what many think, in fact, the eucalypts are not only timber or balsamic species, but carry also splendid flowers.

In southern Australia, we can run into trees of Scarlet Flowering Gum (Eucalyptus ficifolia = Corymbia ficifolia), so much loaded of showy inflorescences, to look like immense red or orange bouquets, and we can have our breath taken away in front of the regular beauty of the flowers of the Eucalyptus macrocarpa, as big as roses. At the Botanical Orchard of Adelaide, where I have photographed this species, I had difficulties in believing to my eyes: the typical tufty stamens of the myrtle were forming a crown of eight centimetres of diameter. At the centre, the tiny style was hardly visible in a cloud of anthers.

In these instances, we might think that the self-fecundation cannot be avoided, but this is not the case. In fact, when the flower blossoms and throws, as a cover, the protective operculum typical of the genus Eucalyptus comes, from the Greek “eu” = “well”, and “kalyptos” = “covered”), while the stamens are already producing the pollen, the pistil has not yet achieved the sexual maturity and cannot receive it for several days.

The fecundation happens, therefore, between different trees, or, at the most, between different flowers of the same tree, and this explains the incredible differentiation of the eucalypts with more than 600 species born during millennia of evolution.

The white, yellow or red flowers can be solitary or united in inflorescences, similar to umbrellas, panicles and corymbs. While studying them, we realize immediately that the reality surmounts the imagination with incredible variants on the same structure.

Pushed by his constant desire of the beautiful and the “different”, the man has later intervened with spectacular hybrids, creating also here “cultivars” as he had done for many other botanical species.

But in the Australian gardens, close to the eucalypts, grow up many other bizarre relatives of the myrtle. The flowers of the Callistemon (from the Greek “kalos” = “beautiful” and “stemon” = “stamen”), resemble, for instance to bottle-cleaners, and, rightly, they are called by the local persons, “Bottle brushes, that is, “cleaners of bottles”.

They can be red or yellow, and have a very long flowering . Analogous is the appearance of the Melaleuca lateritia, with orange stamens and smaller leaves. In this genus, which counts at least 140 species, the five-petals corolla can be visible, like in the Melaleuca pulchella and the Melaleuca steedmanii = Melaleuca fulgens subsp. steedmanii, but, more often, the stamens form some pompons, similar to small fireworks.

Some species do not fear the saltiness and grow up in the lagoons and on the sea sides, with an appearance similar to the pines of our Riviera.

Due to the needle-like leaves and the aspect of the branches, also the Calothamnus lateralis (from the Greek “nice bush”), would look almost like a conifer. Its red flowers, formed by bundles of stamens merged at the base in filaments similar to waist-bands, come out, one on top of the other, like a spike, on the old branches. As they grow on a side only, the popular name of “One-sided bottle brushes”, has been given to them.

Completely unknown to Europeans, the Verticordia, are, on the contrary, called by the Australians “Feather flowers”, due to their red, mauve, yellow and white corollas, rich of fringes similar to the feathers of a bird. They resist long time as cut flowers, and, unluckily, due to the indiscriminate sacks of the past, some species look now almost extinct.

But besides their fanciful flowers, the myrtaceae give us also edible fruits and valued species.

The Feijoa sellowiana = Acca sellowiana of South America, discovered almost one hundred years ago by a Frenchman, and introduced as ornamental plant in the Côte d’Azur, produces big green berries, long up to six centimetres, with a compact and juicy pulp, smelling of Pineapple.

The Eugenia javanica = Syzygium samarangense of Indonesia, offer to local markets some tasty exotic “cherries”, and the Eugenia malaccensis = Syzygium malaccense, a tree with the trunk tall several metres, furnishes “apples” of small size, compact and acidulous. Its big red-purple flowers recall, strikingly, those of the myrtle.

But the most known Eugenia, is, without any doubt, the Eugenia caryophyllata. This species, tall even ten metres, and known also (currently, in 2018, it’s the accepted name) as Syzygium aromaticum, produces the famous “cloves”.

They are not, as many think, fruits, but floral gemmae, dried, which “point” is composed by the calyx and the “head” by the whole of the sepals and petals, still closed, on the stamens and the pistil.

Native of Moluccas, these plants were successfully transplanted in the islands of Mauritius, Réunion, Hispaniola and Martinique, and, nowadays, we have many centres of production in Asia, Africa, and America.

The flowers, rich of aromatic principles and precious ethereal oils, among which the eugenol, besides their use for preparing tasty dishes and famous liqueurs, such as the Alchermès, have important medicinal utilizations in odontology and in the preparation of antiseptics and analgesics.

SCIENZA & VITA NUOVA – 1986

→ To appreciate the biodiversity within MYRTACEAE family please click here.