The aromatic plants. Why they developed aromas. Their history. Cooking and medicinal virtues. Easy to cultivate.

Texto © Giuseppe Mazza

English translation by Mario Beltramini

The Green World hardly escapes from its fate, which is to be eaten by the herbivores, but the plants often are able to limit the damages, and defend themselves from the animals’ greediness, with resolution and incredible ruses.

Where water and food are not lacking, they rely generally on their legendary vegetative capacity, the power to revive, as new, from the most horrible mutilations; but where the life is difficult and the growth slower, they arm themselves of thorns, take shelter in the underground with bulbs or tubers, or adopt the “chemical war”, rendering poisonous the leaves and impregnating them of volatile essential oils, with an intense and warning scent, less appreciated by the palate of the herbivores.

This is the case of the aromatic plants, common in our Mediterranean climate, characterized by long, dry, summers; an habitat where many botanical families, such as the labiatae, the umbrellifers, the lauraceae, or the asteraceae, have elaborated, in a parallel manner, but each one for its own way, balsamic substances, often antiseptic, utilized since the old times, due to their conspicuous medicinal virtues.

Already 2.000 years before Christ, the Egyptian doctors were using abundantly the fennel, the garlic and the wormwood; the “Hanging Gardens of Babylon”, famous for the aromas, were one of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world; and while the Hebrews were inventing the trade of the spices, the Greek mythology was embroidering tales and tales, to explain to the mankind the properties of these prodigious creatures of the world, and their mysterious bonds with the Olympus.

Men and gods transformed in plants, impossible love stories, philtres, potions, ointments and religious rituals; but, above all, they realized at once that the aromatic plants had the capacity of preserving the foods, correct the smell, not always pleasant, of the game, and to foster the digestion of the meats too much high.

Sage and rosemary for the roasts; juniper berries and bay leaves for the brine; thyme and garlic for boiled meats. Very old recipes, bettered during the long medieval sieges, when it was normal to eat mice, and in the refined medieval kitchen of the Renaissance courts, where the cooks were struggling with blows of odorous leaves, for the glory of the great noble families.

Then came the exotic species, appanage of the well-to-do classes, while between the population, the traditional aromas made themselves known in the so-called “Mediterranean cuisine”, according to regional specificities: Genoese pesto, with garlic and basil, Neapolitan pizza with origan, Piedmontese salmis with laurel, sage, thyme and juniper berries.

And nowadays, that the pharmacopoeia has made great strides, and the conservation of the meats is entrusted to the cold, it is rightly this culinary aspect to keep alive the interest for the aromatic plants. Let us look at them, shortly, by families, united often, in the properties and the effects, by the common botanical denominator.

The most generous group, is, by sure, that of the Labiatae, from the Latin “labium”=”lips”.

They can be recognized at once, by their squared section stem, opposite leaves, and asymmetrical corollas, with five petals united, at the base, in a tube which ends up in two fleshy and smiling lips: the upper one, formed by two petals, often joined like a “helmet”, for a better protection of the sexual organs, and the lower one, by three petals, more or less differentiated, often reduced to simple lobes.

When you look at them as they are, mouth wide open, under the burning sun, you might think that they spend the whole day yawning and idling, but the Labiatae are very active plants, full time distillers, which elaborate, incessantly, essences precious for our health and our cooking.

The Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis), with small blue flowers which blossom in spring along the Mediterranean coastline, does not need, it’s sure, any praises. Ideal complement to many dishes and sauces, is a very good digestive, tonic of the nervous system.

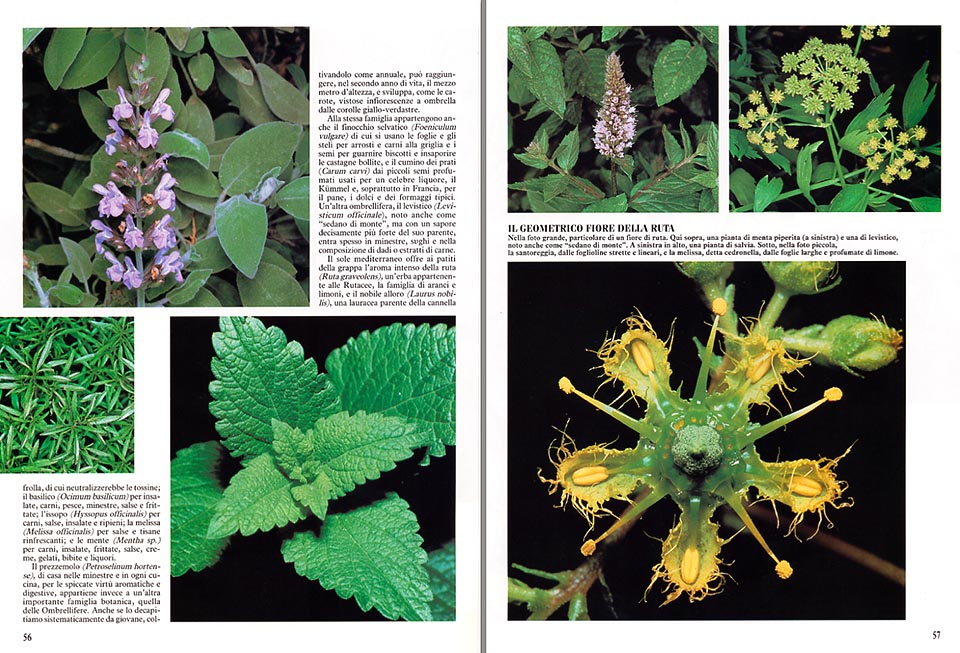

But to the same family belong also the Thyme (Thymus vulgaris), and the Creeping Thyme (Thymus serpyllum), precious for stews, omelets, soups, and grilled meat; the Origan (Origanum vulgare), and the Sweet Marjoram (Origanum majorana), very much used in the sauces and the grilled fish; the Sage (Salvia officinalis), for the roasts, fried foods, and the “white sauces”; the Summer Savory (Satureja hortensis), for fish soups, ball meats, and the too high game, of which seems to neutralize the toxins; the Basil (Ocimum basilicum), for salads, meats, fish, soups, sauces and fried foods; the Hyssop (Hyssopus officinalis), for meats, sauces, salads and stuffing; the Lemon Balm (Melissa officinalis), for sauces and refreshing infusions; and the Mints (Mentha sp.), for meats, salads, omelets, sauces, creams, ice-creams, drinks and liqueurs.

The Parsley (Petroselinum hortense), familiar in the soups and in every cuisine, due to its conspicuous aromatic and digestive properties, belongs, on the contrary, to another important botanical family: the Umbrellifers.

Even if behead systematically when young, cultivated as annual, it can reach, during the second year of life, the height of half a metre, and develops, like the carrots, showy umbrella-like inflorescences, with yellow-greenish corollas.

To the same family, belong also the Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare), of which we utilize the leaves and the stems for roasts and grilled meats, and the seeds, for garnishing biscuits and savouring the boiled chestnuts; and the Caraway (Carum carvi), with the small odorous seeds used for a famous liqueur, the Kümmel, and, mainly in France, for the bread, the seeds, and typical cheeses. Another umbrellifer, the Lovage (Levisticum officinale), known also as “mountain celery”, but with a taste definitely stronger than its next of kin, is often present in soups, gravies, and in the composition of bouillon cubes, or meat extracts.

The Mediterranean sun, offers, to the fans of the grappa, the intense aroma of the Common Rue (Ruta graveolens), a grass belonging to the Rutaceae, the family of oranges and lemons, and the noble Bay Laurel (Laurus nobilis), a Lauracea, relative of the Cinnamon and the Camphor, of which are used the leaves for sauces and meats, and the berries for typical regional liqueurs.

In the warm and dry climates also the Southern wood, or Lad’s Love (Artemisia abrotanum), a shrubby species with bi-pinnate, or tri-pinnate leaves, strictly separated, very suitable for seasoning the grilled meat and the fish when cooked in the oven.

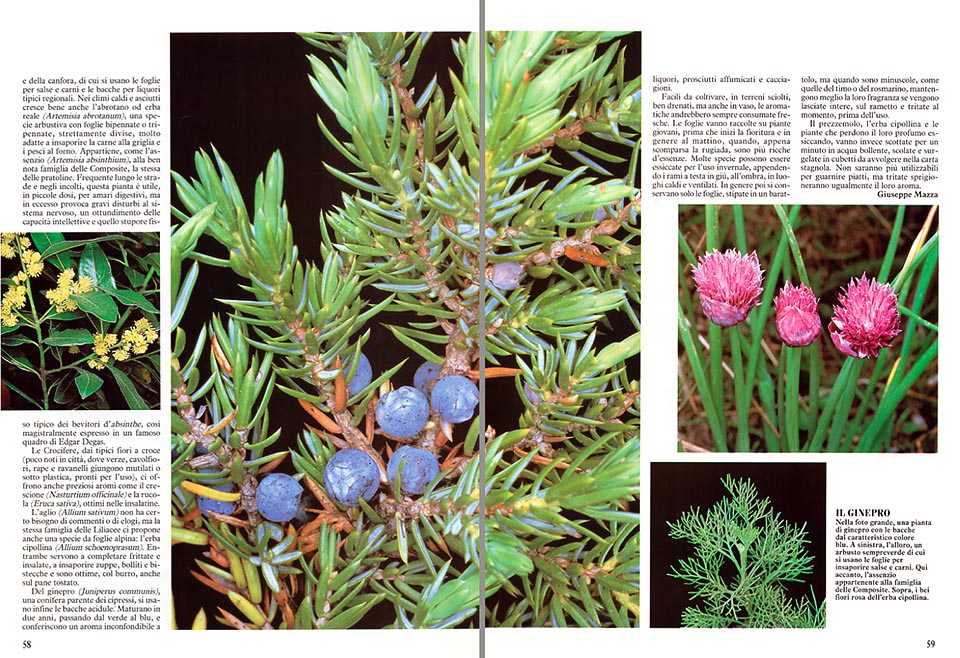

It belongs, like the wormwood (Artemisia absinhthium), to the well known family of the Asteraceae, the same of the lawn daisies. Frequent along the roads and in the uncultivated fields, this plant is useful, in small dosages, for digestive bitters, but, if in excess, causes serious troubles to the nervous system, obtunds the intellectual capacities, and causes that staring stupor, typical of the boozers of Absinth, so wonderfully shown in the painting by Monet.

The Cruciferae, with their typical cross-shaped flowers, unknown in the cities, where savoy cabbages, cauliflowers, turnips and radishes, arrive mutilated, or under plastic, ready for the utilization,offer us also valuable aromas like the water cress (Nasturtium officinale), and the Aurugula (Eruca sativa), excellent in salads.

The Garlic (Allium sativum), does not need, by sure, any comments or praise, but the same family pf the Liliaceae, propses us also an Alpine leaved species: the Chives (Allium schoenoprasum). They are used for completing omelets and salads, to flavour soups, boiled meats, and steaks, and are excellent, with butter, also on toasted bread.

Of the Juniper (Juniperus communis), a conifer relative to the cypress, are, finally, used the acidulous berries. They ripe in two years, passing from the green colour to the blue, and confer an unmistakable aroma to liqueurs, smoked ham, and game.

Easy to cultivate, in free soils, well drained, but also in pot, the aromatic plants should be always consumed when fresh. The leaves are to be picked up on young plants, before the beginning of the blossoming, and, as a rule, in the morning, when, as soon as the dew has disappeared, they are more rich of essences.

Many species can be desiccated for the winter, hanging the branches, head down, in the shade, in warm and ventilated spaces. Usually, then, only the leaves are kept, packed in a small jar, but when they are small, like those of the thyme or the rosemary, they maintain better their fragrance if left intact, on the small branch, and minced on the spot, just before their utilization.

The parsley, the chives, and the plants which lose their scent when getting essicated, must be, on the other hand, scalded for one minute, drained, and deep-frozen in small cubes to be wrapped in silver paper. They will not be any more suitable for garnishing dishes, but, when minced, they will emit, all the same, their precious aroma.

SCIENZA & VITA NUOVA – 1990