Family : Elapidae

Text © Dr. Luca Tringali

English translation by Mario Beltramini

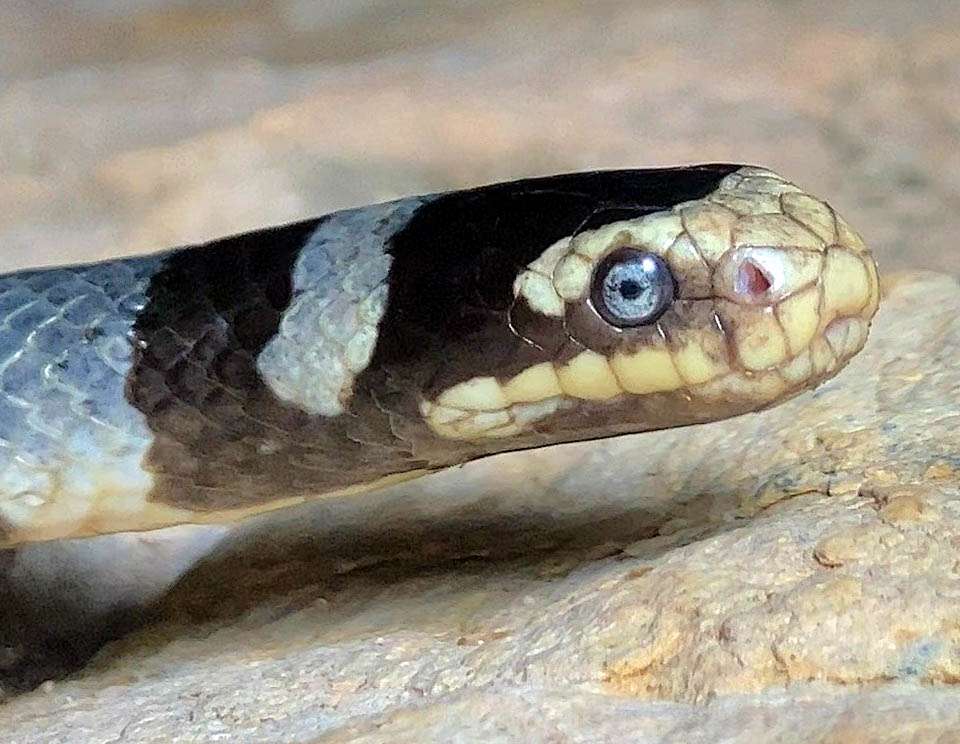

Laticauda colubrina owes its name of Yellow-lipped sea krait to the yellow coloured snout that extends backwards on both sides of the head © uwkwaj

Belonging to the family Elapidae, Laticauda colubrina (Schneider, 1799) is a snake known with several common names: Yellow-lipped sea krait in English; Serpente di mare bocca gialla in Italian; Tricot rayé à lèvres jaunes in French, Nattern-Plattschwanz in German. This “marine animal with a broad tail having the nature as a snake” gets its generic name from the union of the Latin terms “latus”, broad, and “cauda”, tail, with reference to the flattened appearance of the tail; the specific epithet originates, always in Latin, from “coluber”, snake.

Zoogeography

The speciation in the open ocean has been studied for a long time, but the factors that favour or inhibit it still remain unclear. The snakes living exclusively or occasionally in marine and estuarine environments represent about 90% of all species of the extant marine reptiles, are phylogenetically related with the terrestrial Elapidae and are formed by two groups, Hydrophiinae and Laticaudinae

These two groups migrated from the land to the water almost at the same time but, whilst the Hydrophiinae are taxonomically and morphologically more diversified, with more than 160 species recognized in about 50 genera, to the Laticaudinae belongs the only genus Laticauda Laurenti, 1768 with eight described species, probably related with the Australian elapids, and that forms an intermediate stage between the terrestrial and marine snakes.

It is present in the tropical and subtropical coastal waters of east Indian Ocean, South-east Asia and of the western Pacific Ocean archipelagoes © Alwan Syah

These snakes are known as Marine Krait, name coming from the terrestrial Krait like the Banded krait Bungarus fasciatus (Schneider, 1801), because they have on the body some coloured nads very similar. The genus Laticauda has diversified into three groups of species, each one with one species with vast distribution from which have derived one or more ones with restricted range.

– The group with Laticauda colubrina, at ample distribution, and the three species Laticauda guineai Heatwole, Busack & Cogger, 2005 of Papua-New Guinea, Laticauda frontalis (De vis, 1905), of Vanuatu, Laticauda saintgironsi Cogger & Heatwole, 2006 of New Caledonia.

– The group with Laticauda laticaudata (Linnaeus, 1758) diffused in the Indo-Pacific, and Laticauda crockeri Slevin, 1934 only in Rennell Island, Solomon Islands.

– The group with Laticauda semifasciata (Reinwardt, 1837) of South China Sea, Indian Ocean and western Pacific, and Laticauda schistorhynchus (Günther, 1874) of Niue Island between Tonga and Samoa.

The marine Kraits did originate in the so-called Coral Triangle, a geographic zone of vaguely triangular look with the vertices coinciding with northern Philippines, Bali and Solomon Islands. This zone remained thermally stable during the climatic vicissitudes that occurred during the Cenozoic, when the level of the sea in other regions was interested by an alternation of low levels during the glacial periods, with the water trapped in the polar ice caps, and of high levels due to the partial release of that water during the warmest periods.

Even if sighted at 60 m of depth, it mainly lives in shallow waters, at less than 20 m, where looks for prey among corals © Alwan Syah

It is right inside the Coral Triangle that, during the last 30 million years, the genus Laticauda has appeared and has undergone most of the diversification in the present identified species.

The evolution of this genus has occurred in a thermally stable environment, but when the single species expanded their range beyond the Coral Triangle, the most thermally changeable waters caused expansions of the distribution during the warmest periods and contractions during the coldest ones.

The present distribution of this genus extends slightly beyond the Coral Triangle, along its western and northern boundaries, and slightly more extensively towards the south-east.

Among the many adaptations to aquatic life, these semi-marine reptiles with the amphibious behaviour display a vertically flattened tail, nostrils arranged dorsally, and glands regulating the salt present in the organism.

Unlike the other viviparous marine snakes, that never voluntarily leave the aquatic environment, the genus Laticauda is oviparous and obliged to lay the eggs on the dry land where it goes back for reproducing, nourishing and changing skin, spending a large amount of time there.

The mangroves environments, with their high environmental diversity, form essential habitats for the maintaining of healthy populations © Maxime Briola

Laticauda colubrina is one of species with the widest geographical distribution of all the genus, and lives in the tropical and subtropical waters of eastern Indian Ocean, of Asian south-east and the western Pacific archipelagos. Particularly, it is present in India, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, Cambodia, Vietnam, China, South Korea, Japan, Philippines, Fiji, Vanuatu, Samoa, Palau, Tonga, Papua-New Guinea, Australia, New Zealand and New Caledonia. A reliable report concerns a specimen sighted in the Greek island of Kerkyra.

The reproductive range of the Yellow-lipped sea krait is included in the 20 °C isotherm, and beyond this limit it seems that exist only reports of non-reproductive individuals.

A further limiting factor to the distribution of Laticauda colubrina is the presence or absence of dry land with environments suitable for reproduction, explaining the absence of nesting populations of this species in the southernmost band of its range.

Ecology-Habitat

Like the other Laticaudinae, Laticauda colubrina is a semi-marine species, and spends the same quantity of time in the ocean and on dry land. In choosing the habitat it appears essential the availability of a shelter and of clean water.

Laticauda colubrina moves at dusk to beaches close to forests and coral reefs for reproduction, digestion and thermoregulation © Taye Bright

Determinant factors appear to be also the quantity of precipitation and the accessibility to the surface waters as this reptile drinks fresh water or very diluted sea water to regulate its water balance and compensate for its dehydration.

Even if it has been sighted at 60 m below sea level, this snake frequents mainly shallow waters up to a depth of twenty metres.

On the dry land it loves sandy beaches on coral islands and mangrove forests with Sonneratia alba, but always close to coral formations.

Cracks in the trunks of mature or dying trees and decaying sections of the trees of the coastal forests constitute a significant feature of the habitat of this snake.

The cracks in the trees and relatively warm rock appear to be an ideal microhabitat for the incubations of eggs.

When not looking for food this reptile comes down to the soil, often in large numbers on small offshore islands, isolated from terrestrial predators, for thermoregulating themselves alternating periods of light and shadow, looking for a shelter, often in groups of 5-15 individuals, in the cool microclimates of the cracks of the alive or dead trees, to digest the food, to change skin, to mate and lay the eggs.

Due to the dark or black bands, spread like in Bungarus fasciatus along the whole body, this species, of grey-bluish background colour, is called also sea Krait © Billy Gustafianto Lolowang (left) and © ajhg (right)

On the dry land Laticauda colubrina has a greater capacity of thermoregulation than in the water, as the land offers a bigger range of favourable thermal microhabitats.

Recent studies confirm that Laticauda colubrina, that is the species of the genus mre adapted to terrestrial life, is an excellent climber, with movements between ocean and land occurring most often during high tide, especially by night, at times in groups of more individuals.

It seems that the females spend more time on the dry land than the males.

Despite being highly poisonous, if not disturbed it is not aggressive and does not represent a significant threat for human beings.

This species displays a philopatric behaviour, as it tends to remain in its own place of origin or to go back there regularly for reproducing, nourishing and nesting.

The diet of Laticauda colubrina is composed almost entirely by Anguilliformes of the families Muraenidae and Ophichthidae that it locates underwater searching in the crevices by means of the tongue that acts as an olfactory organ. The identified prey is poisoned and then swallowed, usually starting from the head.

The tongue, bearing olfactory molecules to Jacobson’s organ, serves in dry land to probe the environment and find a sexual partner and in water to find the preys © Liu JimFood (left) and © Josy Lai (right)

Prevalently eel-eating, this species also feeds on other bony fish like theStriped eel catfish Plotosus lineatus.

The adult females prey Congridae and Murenidae of medium size in deeper waters, whilst the males prefer to hunt the small shallow-water moray eels, like the White ribbon eel Pseudechidna brummeri or the Snowflake moray (Echidna nebulosa).

The digestion, occurring on dry land, may require several weeks.

Although research on predators of Laticauda colubrina are not abundant, it is however known that the White-bellied sea eagle Icthyophaga leucogaster (Gmelin, 1788) feeds on this species.

Remains of the Yellow-lipped sea krait have been also found in the gastric content of the Tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier).

While swimming this species rotates the tail around its longitudinal axis in such a way that the lateral appearance of the tip of the tail corresponds to the dorsal view of the head.

In this way colouring, drawing, posture and movement of the tail render the latter quite similar to the head, behavioural strategy aimed at avoiding potential predators.

When not diving, the dorsal nostrils, that may be kept closed to prevent water from entering, are maintained open for breathing © Alec Karcz

Morphophysiology

Laticauda colubrina is a medium-large sized snake, as the total length of the males reaches 114 cm, with an average weight of 600 g, and that of the females 170 cm, with an average weight of 1800 g.

Except for the head, the body is cylindrical, slightly compressed and almost uniform in width.

The body is grey-bluish, clear or dark in the upper part and yellowish in the lower one, with evident dark brown and black bands, regularly spaced, whose number varies from 35 to 55, and that are running across the belly.

The yellow colour of the snout extends backwards on both sides of the head, crossing the eye and the upper lip.

Are also known cases of individuals partially black or completely melanic, coming from New Caledonia.

The sexual dimorphism in this species consists mainly in the size, as the females are bigger than the males and have, also, short tail, thin and flattened, whilst the males’ one is longer, less flat and more fleshy.

Underwater nostrils are closed, as seen on the right in the head emerging from waves. For breathing Laticauda colubrina must store air on the surface every 15-25 minutes © Dr. A. Voytsekhovich (left) and © Forest Botial-Jarvis (right)

Unlike most other marine snakes, Laticauda colubrina has maintained the ample ventral scales, as big as half its width, that allow it to crawl effectively on the dry land.

However, it shares with them other characteristics among which a paddle-like vertically flattened tail to aid propulsion in water, valvular dorsal nostrils that may close hermetically to prevent water from entering from the upper part of the snout, glands regulating the percentage of salt, and one single lung extending for almost all the length of the body.

When the oxygen saturation level changes, Laticauda colubrina may alter its skin absorption.

Usually the Yellow-lipped sea krait reduces the subcutaneous vascular perfusion for optimizing swim performances while looking for food, whilst redirects the blood towards the skin surface for maximizing the immersion times.

In water its respiratory cycle consists of a series of fast breaths on the surface followed by a long period of apnea in immersion. Usually this snake dives for 15-25 minutes, but has been reported to stay underwater for more than 50 minutes.

The percentage of salt in the body is kept under control by the waterproof skin, and by a sublingual gland and by the lacrimal glands that expel the salt in excess. The osmoregulation is favoured also by the ingestion of fresh water.

In water has two defense strategies: swims rotating the tail like the head that predators fear due to poisonous teeth, and may stay hidden in ravines more than 50 minutes © Ted Judah (up) and © Chetan Rao (below)

Like the other species of the family Elapidae, Laticauda colubrina is a proteroglyphous reptile, that is with fixed, canaliculated and anteriorly placed poisonous teeth on the jaw with which injects into the prey a very potent neurotoxic poison that attacks the postsynaptic membranes of the muscle tissues and inhibits the acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter that, among other things, regulates the heart contractions and the blood pressure.

Also if the Yellow-lipped sea krait on the dry land is rather docile and even tolerant to a certain degree of human manipulation, it is however essential to avoid being bitten as to this day there are no specific antidotes available.

The bite of this marine snake may initially go unnoticed as it is relatively painless; the symptoms, which can appear within a few hours, vary from individual to individual.

The victim may display nausea, vomit, diarrhea, abdominal pain, headache, loss of consciousness, poor reflexes, fatigue, muscle weakness, swollen lymph nodes, blurred vision, difficulty breathing, dizziness, convulsions and bluish skin.

The victims of poisoning pass away rapidly due to respiratory arrest and subsequent cardiovascular collapse due to cardiac and diaphragmatic failure.

It’s the most terrestrial species of Laticauda genus: moves to dry land for digestion the prey swallowed whole or for thermoregulation alternating sun and shade stay © toby_wood (up) and © Massimiliano Finzi (below)

Ethology-Reproductive Biology

Laticauda colubrina is an oviparous species whose males reach sexual maturity when one year and a half old, whilst the females are sexually mature after about two years.

The male identifies the female exploring the environment with the tongue that captures the volatile molecules and conveys them into the vomeronasal organ, or Jacobson’s organ, the main olfactory system of the snake, utilized for detecting odours and pheromones.

The courting, that may involve more males for one single female, occurs on the dry land during the day, when the males do gather in groups around gently sloping areas during the high tide, usually in the warmest months, from September to December.

The biggest females are preferred as they produce a greater number of eggs.

During mating, which may last more than two hours, the male wraps itself around the female and contracts the body with wave-like spasm pulses, up to 20 per minute.

This reptile is also able to modify its own reproductive period in relation with the seasons climatically more or less favourable: where the average sea surface temperature remains constant between 28-30 °C it can reproduce in any time of the year whilst where it seasonally decreases between 28-26 °C the reproduction happens only once in a year, in the warmest periods.

Before mating, the males gather in groups even in great number looking for a receptive female © gaosou

The females choose grottoes and cracks in the rocks to lay up to 10 eggs per brood, which they deposit on the dry land in small cracks until hatching.

The eggs have thin shells with high permeability to oxygen and water. Only two instances of egg laying in nature have been reported, and therefore the habits of nesting of Laticauda colubrina are still poorly known.

The growth is fast in the young and decreases once the sexual maturity is reached, about 18 months in the males and 18-30 months in the females.

This reptile’s longevity is not known.

Laticauda colubrina is classified as “LC, Least Concern”, at minimal risk in the IUCN Red List of the species under risk of extinction thanks to its vast distribution, and its populations do not appear to be currently in decline.

Anthropic factors such as the loss of habitat and the coastal development related to the increase of tourist activities represent however the main threats for this species.

Among these stand the damage to the coastal habitats necessary for the position of the eggs and the digestion of the preys.

the reproduction happens only once in a year in the warmest periods.The females, bigger than males, have short tails, thin and flat, whilst that of males is longer, less flat and more fleshy. While mating, always occurring on land, the male wraps around the female sometimes contracting the body for more than two hours © dd1003960136 (up) © jamesmifan (below)

As this species is attracted by the light, the coastal lighting renders it highly vulnerable to anthropic activities.

Also global warming can have an impact on the demography of the population of Laticauda colubrina, threatening its reproductive capacity due to the disappearance of the habitats suitable for the deposition due to the rising of the sea level. Also the phenomenon of coral whitening, which causes a significant loss of living organisms, and therefore of prey, is a possible indirect threat to the survival of this species.

The mangrove forests and the old-growth coastal forests, with their high environmental heterogeneity, form essential environments so that Laticauda colubrina keeps healthy populations. As it needs systems of healthy coral reefs and of specific environmental conditions in their terrestrial habitats, some researchers have proposed that this species forms a “flagship species”, inside its distribution area, suitable for promoting an effective management of the marine and tropical terrestrial habitats.

Synonyms

Coluber laticaudatus Linnaeus, 1758; Hydrus Colubrinus Schneider, 1799; Anguis Platura Lacépède, 1790; Platurus fasciatus Latreille, 1801; Platurus colubrinus Wagler, 1830; Coluber platycaudatus Oken, 1836; Hydrophis colubrina Schlegel, 1837; Hydrus colubrinus Begbie, 1846; Laticauda scutata Cantor, 1847; Platurus frontalis De Vis, 1905; Laticauda frontalis Cogger & Heatwole, 2006.

→ For general notions about Serpentes please click here.

→ To appreciate the biodiversity within the SNAKES please click here.